The Irish Medieval Pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela

Published in Features, Features, Issue 3 (Autumn 1998), Medieval History (pre-1500), Volume 6

The cathedral at Santiago de Compostela.

In October 1996 the foundations of what is thought to have been the thirteenth-century Augustinian priory of St Mary were located during building work for a new shopping-centre at Mullingar, County Westmeath. During the archaeological rescue excavation under the direction of Michael Gibbons, more than thirty burials were discovered, two of which contained scallop shells, one of them in combination with a bone relic. Exactly ten years earlier, similar finds of scallop shells had been made by Miriam Clyne during excavations at St Mary’s Cathedral, Tuam, County Galway, probably, as in Mullingar, also of thirteenth/fourteenth century origin. In recent months, a further shell-associated burial site has been located during excavation of the Augustinian friary at Galway. An exciting discovery was made by Fionnbarr Moore in 1992 underneath the wall of a late medieval tomb at Ardfert Cathedral. He found a pewter scallop shell, on which a little bronze-gilded figure of St James had been mounted. The shell was attached to a brooch, clearly defining it as a pilgrim’s badge. The emblem of the shell has always been connected with the apostle James (Jacobus maior) and its occurrence in a burial usually indicates that the deceased had been a pilgrim to the grave of the apostle in Santiago (Sant’Iago i.e. St James) de Compostela in Northern Spain. The twelfth-century Liber Sancti Jacobi mentions stalls selling scallop shells in the proximity of the cathedral at Santiago, and states that returning pilgrims carried these with them, just as Jerusalem pilgrims carried palm-leaves. Fortunately for us, while the palms may not have survived, some of the scallop shells did, thus providing some indication of the extent of the Irish involvement in one of the great pilgrimages of Europe.

The medieval cult of St James of Santiago de Compostela

The emergence of the cult of St James is not easily reconstructed. It seems, however, that the missionary activities of this disciple of Christ’s, before his martyrdom in Palestine in AD 42, as recorded in the Acts of the Apostles, were greatly amplified in the following centuries. The mission of St James was now said to have extended to Spain and by the ninth century martyrologies refer to the translation of the body of St James to Galicia. In conjunction with this development, the apostle now also began to assume the role of patron of Spain, and when the northern Spanish episcopate, in co-operation with the kings of Asturias and Galicia, rediscovered there the long-forgotten tomb of St James, the spectacular rise of Santiago was assured. St James’ alleged missionary activities in Spain were now increasingly a source of inspiration in the ongoing fight against the Moors. Moreover, custody of the apostle’s burial place was utilised to great advantage by the northern kings who were claiming powers similar to those held by the Visigothic hierarchy of the South. The outcome was the establishment of an episcopal, and later archiepiscopal, see at Santiago.

Yet, the popularity of the pilgrimage to Santiago, rivalling that of Jerusalem and Rome, would never have come about, had it not been for a series of circumstances dating to the tenth and eleventh centuries. By this time, the Spanish kingdoms on their side of the Pyrenees had forged close alliances with their counterparts in France, and particularly so with the authorities in Aquitaine and Burgundy. It was in fact French interest in promoting, and protecting, the routes leading from France into Spain, that first opened up the possibility of visiting the shrine at Santiago in relative safety. The powerful Burgundian abbey of Cluny, in particular, established and controlled numerous monasteries along the pilgrims’ routes and aristocratic families on both sides of the Pyrenees followed this example with foundations of their own. These also established hospitia and assumed responsibility for the general upkeep of the route.

The pilgrims’ route to Santiago

The eleventh century generally was also a time when travel, hazardous during the invasions of Vikings, Saracens and Magyars, became widely possible again. Pilgrimages to all kinds of shrines were now undertaken with renewed effort. In these more peaceful circumstances the abbey of Cluny began eagerly to promote pilgrimages to as far afield as Jerusalem and Santiago. And it was the Cluniac message of the ‘overriding importance of the remission of sins’ that sparked off an unprecedented wave of pilgrimage throughout Europe. The foundation by noblemen of monasteries, churches and hospices, including those along the pilgrims’ routes, ‘for the salvation of their souls’ can be linked to this phenomenon.

The Mullingar excavation. (Westmeath Examiner)

The popularity of the pilgrimage to Santiago increased even further with the composition in the early twelfth century of the Liber Sancti Jacobi, a work written specifically with the intention of glorifying the saint. Amongst other items it contains a guide to the pilgrims’ routes and a list of the saint’s miracles. An implied authorship of the text by Pope Calixtus II (1139-45) and an address it contains to the abbot of Cluny, give a strong indication of the parties involved in its composition. Furthermore, the text extols not only the merits of the holy places in Santiago itself but also, significantly, those of the churches along the pilgrims’ routes, and notably those in France.

By the twelfth century, then, the routes to Santiago had become firmly established. Four major roads traversed France, often along already established Roman roads or trade paths, separately crossing the Pyrenees in order to come together at Puenta la Reina near Pamplona. From here a single route continued on to Santiago for a further 600 km. The southern and middle approach routes on the French sides of the Pyrenees, which passed through Le Puy, Limoges and Toulouse, were frequented by pilgrims from Burgundy, Italy, Hungary, Austria and Southern Germany. It was, however, the northern one, which took in visits to the grave of St Martin at Tours that was most popular with French, Flemish and Northern German pilgrims. Moreover, it is at the port of Bordeaux, long established as a trading point with Britain and Ireland, that many Irish pilgrims are thought to have joined the other groups.

Irish pilgrimage

The concept of pilgrimage was well known in Ireland. Already during the early Middle Ages peregrinatio was an ideal followed by many, in particular by clerics. Yet, in most cases it differed from what we now consider to be a typical pilgrimage and what was also the medieval Continental equivalent: a journey to a holy site with the intention of returning. In what Kathleen Hughes calls ‘perpetual pilgrimage’, the Irish pilgrims typically betook themselves to remote areas in and around Ireland, Britain and the Continent. They were driven either by religious motives, by the urge to expiate their sins or by mere wanderlust, but they rarely returned. Instead, they were instrumental in founding religious houses abroad or otherwise gaining employment in a monastery along the way. Equally, when the historical record speaks of the commencement of a peregrinatio to a monastery within Ireland, more often than not the reference is to a journey undertaken at life’s end in the knowledge that there will be no return. In fact, the records of most of those that participated in the Irish peregrinatio survive only in the archives of the Continental monasteries they chose as their new homes. The Irish annals rarely mention expatriates. By leaving the country, pilgrims seemingly ceased to exist for those keeping Irish records.

References to organised voyages to visit famous shrines with the intention of returning home are rare in Ireland. This applies equally to journeys of pilgrims within the country. Regrettably, therefore, we possess few travel reports or itineraries similar to those that survive from other countries. Yet, the upsurge in the practice of pilgrimage during the eleventh century seems also to have had its effect in Ireland. The annals testify to the journeys of both nobles and clerics to Rome, often, however, only to record their deaths abroad. This may indicate that some of them travelled towards the end of their lives, with no great hope of return.

The Mullingar excavation-note the scallop shell. (Westmeath Topic)

The pilgrimage to Santiago

Bearing in mind that official visits by the Irish clergy to the Papal court could be combined with pilgrimage, it is not surprising that journeys to Rome received most coverage. The other two important destinations, Jerusalem and Santiago, being more arduous and demanding, were understandably accessible to fewer pilgrims. Rare as references to Jerusalem may be we have the good fortune of possessing the itinerary of an Irish pilgrim, the Franciscan brother Symon Semeonis, who left Ireland together with his companion Hugh le Luminour, another Irishman of Anglo-Norman descent, in 1322. His observant and detailed account provides us with a wealth of information.

The pilgrimage to Santiago receives hardly any mention in Irish documents before the fifteenth century so we have to rely on Continental sources for information. The Irish Benedictine monasteries in Southern Germany, the Schottenkloster, whose beginnings can be traced back to the late eleventh century, are a very strong reminder of the impact of the Irish peregrinatio abroad. Hundreds, if not thousands of Irishmen (and some women) left their country to become members of these communities. Thus, it does not come as a surprise that the mother house at Regensburg, and some of its most important dependencies, were dedicated to St James who had by now become the universal patron of pilgrimage. We know that at least one of the monasteries, St James at Wurzburg, possessed a relic of its patron, which is said to have been presented by the local bishop at the consecration in 1139.

It was in the scriptorium of the mother house that a history of Irish peregrinatio was written in the thirteenth century. Here we are told that 30,000 saints, some of them old and debilitated, left Ireland with the permission and benediction of St Patrick, one group setting off for the Holy Land, the other for Rome. A third group left to visit the graves of the apostles, including that of beatissimus Jacobus in Compostela. It was of course in the author’s interest to promote pilgrimage, having come to Germany as a peregrinus himself, but we can also detect from this work that, by the thirteenth century, pilgrimage from Ireland to all of these places must have become quite popular.

Evidence from Ireland itself tends to confirm this. Foundations of pilgrims’ hostels in ports such as Dublin in 1216 and Drogheda where St James’ Street and St James’ Gate still evoke the original dedication, testify to an increased Irish participation. These hostels, catering for pilgrims who might have travelled long distances overland already, most probably also existed in other harbour towns, such as in those of the South and West, accustomed to trade relations with France and Spain.

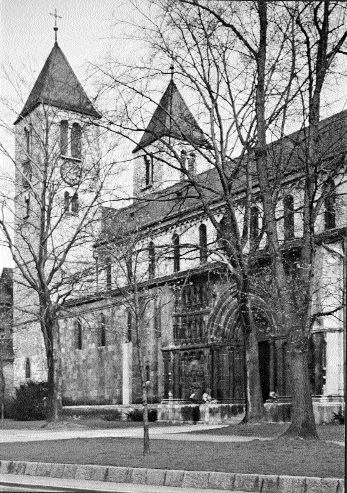

The Irish Benedictine monastery at Regensburg, Southern Germany, was dedicated to St James. (Schnell and Steiner)

It is indeed plausible that pilgrims would have used established trade routes, and that the ships that brought goods to and from Ireland also provided berths for pilgrims. This would almost certainly have been the case for pilgrims taking the boat to Bordeaux or to other ports of the Saintonge before joining others on the via turonense, the overland route to Spain. Unfortunately, however, documentary references are mostly only to taxable goods contained within cargoes and not to passengers. By the fifteenth century, however, references to Irish pilgrims begin to feature more often in documents. At this stage, the direct route by boat to the port of La Coruna, north of Santiago was preferred by many. Indeed, the ‘maritime pilgrimage’ now undertaken by Irish and British pilgrims brought about a significant increase in numbers. Although the journey through the Bay of Biscay was certainly nothing to look forward to, once in La Coruna, Santiago could be reached by a comparatively short walk. Ships left Ireland for Spain from Drogheda, Dublin, Wexford, New Ross, Waterford, Youghal, Cork, Kinsale, Dingle, Limerick and Galway, while other Irish pilgrims are thought to have joined their fellows in British ports, particularly Bristol and Plymouth.

Despite the fact that this form of pilgrimage must have been easier than the overland journey, we have many accounts of difficulties encountered by the travellers. Four-hundred Irish pilgrims, returning from Santiago in 1473 on board the vessel la Mary London, for example, were attacked and captured by pirates before eventually being allowed to land in Youghal. Similarly, during the fifteenth century the annals report the loss at sea of many Irish pilgrims, some of them chieftains. Others died soon after their return. These spectacular events naturally impressed themselves on chroniclers, whereas references to the many voyages completed successfully would have been of less interest. Between the middle and the end of the fifteenth century many hundreds or thousands of Irish people, with only the more powerful among them mentioned in documents, must have embarked on pilgrimage. An interesting example is provided by the two pilgrimages of James Rice, Lord Mayor of Waterford, in 1473 and 1483. He had to apply for leave from his office, and testimony to his great devotion to St James is still visible in a side-chapel of Waterford Cathedral, which he built in honour of the saint.

After the initial upsurge of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, recurrent plagues and warfare during the fourteenth century had greatly hindered travel. By the fifteenth century, however, both the local economy and native Irish fortunes had taken a turn for the better. The resurgence of the Gaelic families brought new confidence, and saw them join their Anglo-Norman compatriots in the foundation of monasteries and in the reinvigoration of religious life. This new prosperity, together with the improvement of ships and navigation, made for expanded trade and also incidentally benefited pilgrimages abroad. The fifteenth century can thus be described as a veritable century of pilgrimage. This was, however, to be once more hindered by the Reformation which heralded a substantial decline in the practice over the next few centuries.

Modern interest in pilgrimage

The present century is witnessing an unprecedented revival of pilgrimages in general and of the pilgrimage to Santiago in particular. The ‘way to Santiago’ has been adopted as a theme by the European Community, signalling the unifying character of pilgrimage from all over Europe. Every year, thousands of people retrace the steps of their medieval forefathers, many of them on foot, horse or even by bicycle. When the Puerta Santa, the door of the cathedral, closed on 31 December 1993, it was reckoned that some three million pilgrims had visited Santiago during that Holy Year. At the same time, research on all aspects of pilgrimage has been blossoming. The publications of Peter Harbison on pilgrimage in Ireland and of Roger Stalley on Santiago have led the way here.

Statue of St James at Regensburg c. 1310/20. (Schnell and Steiner)

Many issues still await to be addressed, however, such as whether medieval Irish architecture shows signs of having been influenced by what the pilgrims saw abroad. The still not satisfactorily explained source of the Hiberno-Romanesque style, or at least of certain of its motifs, may well have had something to do with the style of churches encountered by pilgrims abroad. On the other hand, Stalley has quite rightly pointed out that in the heyday of Irish pilgrimage during the fifteenth century, Irish pilgrims were travelling by ship:

while the sea routes helped to sustain the popularity of Santiago, they did little to broaden the mind of the many thousands who set sail from the northern ports each spring and summer.

Yet, the extent of the impact of pilgrimage during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries is slowly coming to light. Excavations such as those at Mullingar and Tuam add to our knowledge, as does research into the religious institutions of the newly founded towns. The role of the Anglo-Norman monasteries outside the gates of the city walls as hospices for pilgrims is now under review, as is the close connection of the orders of the Templars and Hospitallers with the pilgrimage to Jerusalem.

Following the example of the Continent, pilgrims’ routes within Ireland are now also generating interest. Some, such as Tochar Phadraig in County Mayo, which leads from Ballintubber Abbey to Croagh Patrick, and St Declan’s Way from Cashel to Ardmore, have been reconstructed and are being promoted by local enterprise. Other routes are being researched and developed. ‘The way to Santiago’ has become a metaphor for our generation as it approaches the year 2000 with all the connotations this has. Indeed, ‘pilgrimage’ has been adopted by the Irish Heritage Council as its motto for the millennium year. An international conference on all aspects of pilgrimage, foreign and Irish, will take place at the National University of Ireland, Cork during that year. It is hoped that during this conference both scholarly interest in the subject and practical experience of pilgrimage will come together. It is important that Ireland, with her long tradition of peregrinatio, should be involved in this new-found interest in one of the great unifying experiences of medieval and modern lives.

Dagmar Ó Riain-Raedel lectures in medieval history at the National University of Ireland, Cork.

Further reading:

M. Clyne, ‘A Medieval Pilgrim: from Tuam to Santiago de Compostela’, Archaeology Ireland 4.3 (1990).

P. Harbison, Pilgrimage in Ireland: the monuments and the people (London 1991).

R. Stalley, ‘Sailing to Santiago: medieval pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela and its artistic influence in Ireland’, in Ireland and Europe in the Middle Ages: selected essays on architecture (London 1994).

I would like to thank Fionnbarr Moore, Michael Gibbons, Jim Higgins, archaeologists and Ray Linehan, Westmeath Topic and John Mulvihill and Eilis Ryan, Westmeath Examiner, for their help.