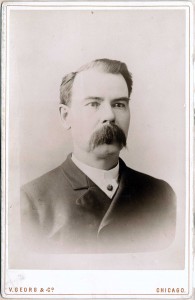

In 1882 an Irish doctor, Patrick Henry Cronin, arrived to take up his new position at Cook County Hospital in Chicago. Cronin quickly established himself as an active member of the Irish community in the city. He was a prominent member of a number of charitable societies, regularly sang in the Catholic Cathedral on State Street and, most important of all, was an active member of Clan na Gael. The Clan was a secret Irish republican society founded in New York in 1867. Like its predecessor, the Fenians, the Clan was dedicated to winning Irish independence from Britain through the use of force. Cronin was keen to rise through the ranks and his ambition quickly brought him into conflict with local Clan leader Alexander Sullivan. Sullivan was a controversial figure, inspiring great loyalty and great hatred, and by 1881 he had become the undisputed leader of the Chicago Irish and one of the most influential leaders of radical Irish America. Sullivan was the leading member of ‘the Triangle’, a triumvirate that controlled Clan na Gael. Throughout the 1880s Chicago was the centre of all Clan activity, and Sullivan’s influence was enormous.

In 1882 an Irish doctor, Patrick Henry Cronin, arrived to take up his new position at Cook County Hospital in Chicago. Cronin quickly established himself as an active member of the Irish community in the city. He was a prominent member of a number of charitable societies, regularly sang in the Catholic Cathedral on State Street and, most important of all, was an active member of Clan na Gael. The Clan was a secret Irish republican society founded in New York in 1867. Like its predecessor, the Fenians, the Clan was dedicated to winning Irish independence from Britain through the use of force. Cronin was keen to rise through the ranks and his ambition quickly brought him into conflict with local Clan leader Alexander Sullivan. Sullivan was a controversial figure, inspiring great loyalty and great hatred, and by 1881 he had become the undisputed leader of the Chicago Irish and one of the most influential leaders of radical Irish America. Sullivan was the leading member of ‘the Triangle’, a triumvirate that controlled Clan na Gael. Throughout the 1880s Chicago was the centre of all Clan activity, and Sullivan’s influence was enormous.

Cronin expelled from Clan na Gael

As part of the Dynamite Campaign of the mid-1880s a fund was established by the Clan to look after the families of the dead and jailed dynamiters. Cronin, however, suspected that some of the money had been siphoned off by Alexander Sullivan, and after some investigation he concluded that Sullivan had stolen $100,000 of Clan funds. Cronin’s attempts to get Sullivan to account for the missing money failed, and in 1885, disillusioned and desperate, he decided to make public his allegations. Sullivan took immediate action. He accused Cronin of treason, ordered an internal Clan trial and assembled a panel of five men to try him. Two of those appointed to the panel were Henri le Caron, a Frenchman who had been involved in the failed Fenian invasions of Canada in the late 1860s, and Daniel Coughlin, an associate of Sullivan’s and a senior detective in the Chicago police. The trial was brief; Cronin was found guilty and expelled from Clan na Gael in the spring of 1885.

Cronin’s expulsion split the Clan. Nowhere was the division more obvious than in Chicago, where many members of Clan na Gael sided with Cronin. The public acrimony damaged the reputation of the Irish in America and for three years attempts were made to reconcile the two wings of the Clan. Finally, at a convention in Buffalo, New York, in June 1888, representatives of Clan na Gael agreed to hear Cronin’s evidence against Sullivan and the other Triangle members. A six-man committee was proposed, with three men representing each side of the dispute (Cronin sat on the prosecution side, le Caron on the defence). The Triangle was found ‘not guilty’ by a vote of four to two. Cronin was furious, and determined to prove Sullivan’s guilt. Ten months later he was dead.

‘Henri le Caron’ revealed as a spy

After the 1888 convention Cronin returned to Chicago, while Henri le Caron headed for London. At the time London was in the midst of a sensational judicial inquiry—the ‘Parnell Commission’. Charles Stewart Parnell had been the subject of a series of controversial articles, published by The Times, entitled ‘Parnellism and Crime’. These articles implicated Parnell in the 1882 Phoenix Park Murders, and accused him of close links with secret revolutionary groups such as the Fenians and Clan na Gael. Parnell denied all charges and a parliamentary commission was established to investigate the newspaper’s claims. The proceedings ran for fourteen months, and in February 1889 a key witness gave sensational evidence. Taking the stand, le Caron revealed that he was not a Frenchman dedicated to the cause of Irish freedom but an Englishman called Thomas Beach who had been a spy for the British government for 25 years.

Le Caron claimed to have met Parnell a number of times and was adamant that Parnell knew of Clan na Gael’s plan to use violence to achieve Irish freedom. It was le Caron’s information that had formed the basis of several of the articles in The Times, and his reports that had been responsible for the capture of many of the men sent on bombing missions to Britain as part of the campaign. Thanks to his senior position in Sullivan’s Chicago camp, le Caron had an intimate knowledge of the workings of Clan na Gael and had furnished Scotland Yard with all the information they required.

Cronin now suspect

The revelation that Henri le Caron was a British spy sent shock waves through Irish America. Le Caron had intimated that there was more than one spy at work in Clan na Gael and, in Chicago, attention immediately focused on Patrick Cronin, Sullivan’s bête noir. The uneasy truce that had been engineered at the Buffalo Convention looked increasingly precarious. Cronin told friends that he believed that his life was in danger. Nevertheless, in April 1889 Cronin struck a peculiar deal with a Patrick O’Sullivan, an iceman with a factory in Lake View (a northern suburb of Chicago). Despite living several miles from the icehouse, Cronin agreed to attend any employee of O’Sullivan’s who was injured in return for a regular stipend.

On 4 May an anxious young man summoned Cronin from his surgery. An accident had taken place at O’Sullivan’s icehouse and a man had been seriously wounded. Cronin packed his medical case and leapt into the waiting buggy. When he failed to return home, his landlords and friends, Theo and Cordelia Conklin, reported him missing. At first, however, the police investigation was characterised by apathy. Daniel Coughlin, a detective assigned to the case, reflected the feelings of many officers when he announced to reporters: ‘Boys, I give up … I’ve searched high and low until I’m exhausted and I can get nowhere. But this you may be sure of, there isn’t a shred of evidence that Cronin was murdered.’

Cronin’s friends pointed to the fact that several patrolmen had reported the erratic passage of a horse and cart carrying a large trunk through the streets of Chicago late on the evening of Cronin’s disappearance. The following day the discovery of a blood-stained trunk containing tufts of human hair in a ditch gave substance to the view that Cronin had not disappeared voluntarily. But other rumours persisted. The press claimed that he had run away: to Canada, to escape prosecution for performing an abortion; to New York, to escape the consequences of an ill-advised affair; or to London, where, like le Caron before him, he would be revealed as a British spy.

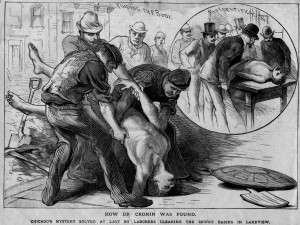

Putrid smell

All speculation ended on 22 May when employees of the Board of Public Works were dispatched to investigate the source of a putrid smell coming from a sewer in Lake View. Peering through the bars of the sewer, the workers saw the swollen body of a naked man. A bloody towel was draped around the corpse’s neck and he had been stripped of all belongings, with the exception of an Agnus Dei medallion, a Catholic sacramental believed to safeguard the wearer against harm. It was immediately assumed that the body was Cronin’s, and within hours the Conklins identified his body in the morgue of Lake View police station.

Two days after the discovery of Cronin’s body the police found the scene of his murder. The Carlsons, Swedish immigrants, owned a cottage in Lake View that they rented out. On 20 March a ‘Frank Williams’ had rented the cottage but in May he vacated it without notice. On entering the empty cottage, the Carlsons discovered rooms stained with blood and scattered with broken furniture. Meanwhile, the police investigation was finally gathering pace. Patrick Dinan owned a livery stable very close to East Chicago Avenue police station. The stable was regularly used by police officers and detectives, and on the night Cronin was killed Dinan had rented a horse and buggy to a man called ‘Smith’, sent by Detective Daniel Coughlin (the detective assigned to the case and a Clan member who had expelled Cronin in 1885). The horse and buggy matched the newspaper descriptions of the ones that had taken Cronin from his surgery, and Dinan reported this to the chief of police, George W. Hubbard. On 27 May Detective Coughlin was arrested and charged with the murder of Dr Cronin. The iceman, Patrick O’Sullivan, was also taken into custody.

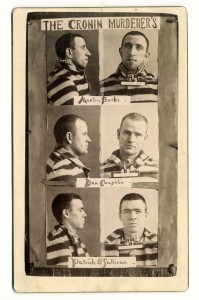

As the police investigation continued, growing evidence led officers to the conclusion that Cronin’s murder was the result of a conspiracy hatched in Camp 20 of Clan na Gael, Alexander Sullivan’s camp. It became apparent that Patrick O’Sullivan, the iceman, was closely linked with Martin Burke (the ‘Frank Williams’ who had rented the Carlson cottage). Further revelations implicated John Beggs, the senior guardian of Camp 20, and a number of others associated with both Sullivan and Camp 20. On 11 June Alexander Sullivan was arrested, but with little more than rumour to detain him he was released after one night. On 16 June a key suspect was traced to Winnipeg. Martin Burke was discovered at Winnipeg railway station, travelling under an alias, with tickets for a boat bound for Liverpool. After lengthy extradition proceedings, Burke was returned to Chicago on 5 August. In all, the Chicago police identified nine men whom they believed were involved in the conspiracy to murder Cronin, but several of those suspected were never arrested and charged.

Jury selection

By the time the Illinois state attorney was ready to bring Coughlin, Beggs, Burke and O’Sullivan to trial, however, it was almost impossible to select a jury. Almost everyone in Chicago had already made up their minds about the case. From May to December 1889, thousands of newspaper reports and editorials had been dedicated to the Cronin murder. Every twist and turn of the investigation was closely scrutinised by a press and public who were fascinated and horrified in equal measure. The newspaper coverage was sufficient to convince many Chicagoans that Coughlin and his cohorts were guilty. Between August and October, 1,115 men were interviewed as potential jurors (at the time the largest and longest jury selection process in US history) before twelve were eventually sworn in on 22 October. The trial opened the following day. Such was the interest in it that 5,000 members of the public attempted to gain admission to a courtroom that could accommodate just 200.

The trial lasted for seven weeks, and every twist and turn was pored over and dissected by an enthralled city. Newspapers delighted in providing minute details about the lives of the accused, the jury and the legal teams. As the days wore on, Clan na Gael slowly unravelled, as unedifying details of the inner workings of an idealistic but corrupt movement were exposed to public scrutiny. By the conclusion of the trial few in Chicago were prepared openly to defend the cause of Irish republicanism.

The jury began its deliberations on 12 December. Outside the divided Irish American community, popular opinion held that the accused were guilty and should hang. It became apparent on the morning of 16 December that a verdict was imminent, and a huge, silent crowd waited outside the court in a fine rain. Coughlin, O’Sullivan and Burke were found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment, while Beggs was acquitted. Supporters of Sullivan rushed to embrace the verdict, claiming that since Beggs, the leader of Camp 20 and therefore the leader of the alleged conspiracy, had been found innocent, this was proof that there had been no conspiracy and that Cronin had been murdered by individuals acting on their own behalf. Such subtleties were lost on the general public, who remained convinced that Cronin was an innocent man murdered because he exposed corruption within Irish America.

In late January 1890 the three prisoners were dispatched to serve their terms in Joliet prison. From prison Daniel Coughlin waged a strong campaign to be granted a retrial, and in 1893 the Illinois Supreme Court agreed. Burke and O’Sullivan had died of tuberculosis in 1892, so Coughlin was the only man to enter the dock, where he was cleared of all charges and released. There is little doubt that the jury was bribed.

Gillian O’Brien is senior lecturer in history at Liverpool John Moores University.

Read More: Dynamite Campaign

More than a crime story

Further reading

S. Kenna, War in the shadows: the Irish American Fenians who bombed Victorian Britain (Dublin, 2013).

G. O’Brien, Blood runs green: the murder that transfixed Gilded Age Chicago (Chicago, 2015).

N. Whelehan, The Dynamiters: Irish nationalism and political violence in the wider world, 1867–1900 (Cambridge, 2012).