Popular culture has long been used in Europe in the construction of ‘national’ ideologies. With the development of the strong nation-state in Europe, elites have also tried to suppress or assimilate elements of popular culture which they regarded as threatening to order, whether civil or moral. In many countries, dance has been prominent in this process involving as it does popularly-organised large scale gatherings (civil) and elements of sexual display and contact, as well as stylistic elements regarded by the elites as undesirable – rough, coarse or rude (moral). This article looks at these processes in the development of ‘Irish’ dancing from the late nineteenth century to the present. At the very end of the nineteenth century, the nationalist cultural movement consciously set out to develop a national dance style and repertoire based on existing popular dance practices.

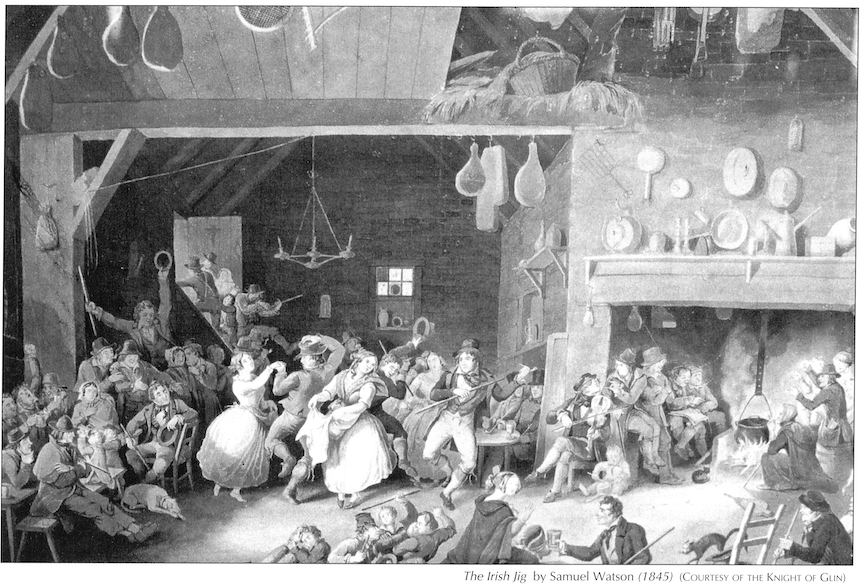

Ballroom daysIn the urban upper class ballroom milieu, the most popular form was ‘country dance’. Hundreds of these were published each year in the early part of the century. In 1816, in Dublin, the quadrille was introduced. Later, various round dances such as the valeta, the barn dance, the Schottische, the military two-step and the waltz became popular. In the rural areas, at local cross-roads dances and at house-dances the Moinin jig (for two or four), reels, country dances and in the late nineteenth century the Barn dance, the highland Schottische (setish), the varsovienne (shoe the donkey) and the quadrilles became popular. Solo dances such as the hornpipe, the jig and the reel were also popular. The dancing masters taught dance in the ‘big houses’ of the gentry, in towns, and amongst the country people. Concepts of ‘refinement’ were very important to them. They sought to modify the native dance style. Arm movements, which had been a feature of Moinin jigs, were suppressed. High kicks, finger snapping and other ebullient movements were curtailed or discouraged. The dancing masters also developed group dances which combined native jigs and reels with quadrilles and country dance forms. The invention of tradition: the first céilíIn the late nineteenth century, cultural events were developing which resulted in the introduction of new forms and concepts into Irish dance. The most important was the foundation of the Gaelic League (Conradh na Gaeilge) in 1893. The League was founded primarily to promote the Irish language and initial involvement in dance was peripheral. Surprisingly, the impetus came from London. One of the most energetic and charismatic of the League’s organisers, Fionan Mac Coluim, was working as a clerk in the India Office in the late 1890s. Also prominent in London was J.G. O’Keefe who worked in the War Office. Whilst their Irish language classes were operating successfully, they were keenly aware of the lack of a ‘social dimension’ to their activities, particularly when they attended some lively Scots ‘ceilithe’ nights in London. Mac Coluim and others decided to take positive action and the first ever ‘céilí’—a term borrowed from the Scots—was held in London in the Bloomsbury Hall near the British Museum on Saturday 30 October 1897. The dances known to the company were limited to the jig, the quadrilles and the waltz, which were performed by ‘Fitzgerald’s Band’ to Irish airs in honour of the occasion. The contrast between this ‘céilí’ and the Scots ‘ceilithe’ with its profusion of dances was not lost on Mac Coluim. He fretted over the problem until fate intervened in the form of an introduction to ‘Professor’ Patrick D. Reidy, a resident of Hackney, who had been a dancing master in west Limerick and in his native Kerry in the late 1880s. Reidy’s first classes for Gaelic League members were held in the Bijou Theatre off the Strand. He taught group dances such as the eight-hand reel, the High Caul Cap, and a ‘long dance’ sometimes termed by Reidy the ‘Kerry reel’ and sometimes the ‘old traditional rinnce fada from Kerry as mentioned in the poem “Cill Cais”‘. The excitement generated by the discovery of these dances led to a desire to further explore the field and a group journeyed to Ireland on collecting trips. The search was confined largely to County Kerry with its image of the romantic ‘Celtic West’. There was also a presumption that Munster dance was superior because of the influence of the dancing masters. (This attitude was paralleled among language revivalists, who favoured the Kerry dialect of Irish as the national standard because they considered it more literary). Collection was always very random. The main concern was to develop a new canon of ‘Irish’ social dance, not to carry out surveys.

The London Gaels presented performances of four – and eight-hand reels at the Oireachtas (Annual Conference) of 1901. Controversy ensued when some observers dismissed the dances as versions of the quadrilles which were classified as alien and thus unsuitable for nationalists. Also excluded as foreign were social dances such as the highland Schottische, the barn dance and the waltz, despite the fact that they were part and parcel of the repertoire of the ordinary people of rural Ireland amongst whom traditional dance was strongest. Simple group dances such as the ‘Walls of Limerick’, the ‘Siege of Ennis’ and the ‘Haymaker’s Jig’ were taught at Gaelic League branch meetings nationwide in the early years of this century and they still form part of the repertoire at modern céilís. As well as dance forms, the Gaelic League codifiers also applied themselves to the style of ‘stepping’ in Irish dance. Following the tendency to favour the Munster style and discourage all others, attacks were made on the styles of the north and west. A correspondent in the Western People, a Connacht newspaper, said in 1904 of dancing locally: ‘In some instances there was a tendency to clog-dancing and other displays more suggestive of English than of Irish style’. In 1906, a commentator on the northern style said: ‘It is a series of “batters” – more batters indeed than the best Irish dancer would be called on to execute and the pity is that those whose wonderfully intelligent feet mistake the ‘clog’ for the real article should not have the opportunity of practising the real Irish hornpipe‘ (my italics). Here again we have the tendency to counterpose ‘foreign’ to ‘Irish’. The west Galway or ‘sean-nós’ style, more ‘flat-footed’ than the Munster style and often featuring flamboyant arm movements frowned upon by the Munster dancing masters, was also rejected. The end result has been that an extreme modification of the Munster style is now presented as the national style where Irish dancing is concerned. ‘Irish dances do not make degenerates’This process of selection was paralleled in the attempted creation of a new milieu for dance. Ceilis were held in local halls and schools separate from the locations traditionally favoured by the people – the house, barn or cross-roads. The more formal dances organised by the Gaelic League found favour with the Catholic clergy who had long fulminated against the country house dances. In 1925 the Catholic bishops attacked the evils of late-night dancing and gave their seal of approval to the Gaelic League dances: ‘They may not be the fashion in London or Paris. They should be the fashion in Ireland’. They observed that ‘Irish dances do not make degenerates’. The combined opposition of church and state to informal dances which were outside their control led to the passing of the 1935 Public Dance Hall Act which confined the holding of dances to places licensed for such a purpose and which imposed a government tax on the admission price. According to Junior Crehan, a noted fiddle player and folklorist from Mullagh, County Clare: They believed that there was immoral conduct carried out at the country houses and that there was no sanitary arrangements, that was their excuse. You had to pay three pence tax to the shilling going into the hall which meant money to the government. They didn’t care if you made your water down the chimney as long as they collected the money.

Helen Brennan is a post-graduate research student at the Department of Social Anthropology, Queen’s University, Belfast.

Further reading:

J.C. O’Keefe & A. O’Brien, A handbook of Irish dances (Dublin 1912, 1954).

T. Moylan, Irish dances (Dublin 1984).

T. Lynch, Set dances of Ireland (San Francisco 1989).