by Andy Bielenberg

A distillery was first established in Kilbeggan in 1757 when there was a proliferation of small distillers setting up in the midlands. They were attracted by the quality and availability of barley in the region, which was (and still is) the distiller’s greatest cost, and of turf from the extensive local bogs. The dramatic growth in the popularity of whiskey accelerated the development of the industry and by 1782 there were three small distillers operating in Kilbeggan. When the Dublin parliament introduced more stringent excise laws in the 1780s, the industry experienced deterioration and contraction, matched by a corresponding rise in illicit production. This filled the void left by the closure of numerous small rural distilleries, including those in Kilbeggan, all of which had gone under shortly after the turn of the century.

1830s distilling boom

In 1823 these excise laws were replaced by a more progressive regime. Consequently the industry entered a new phase of expansion. Distilling was re-established in Kilbeggan on a much larger scale by the Fallon brothers, midland tobacconists with businesses in Tullamore and Mullingar. Changes in the scale of operations are evident; ten times as much whiskey was produced in the 1825-6 season than at the turn of the century, and growth continued as the business cashed in on the distilling boom of the 1830s. Ireland’s per capita consumption of whiskey during that decade has never been surpassed.

Economic depression and the temperance movement

A combination of economic depression and the rise of the Temperance movement ended the boom and ushered in an altogether less indulgent decade. As a result of the downturn the Kilbeggan distillery had to shut down again. It was at this point in 1843 that the Lockes became involved. They were small-time merchants from Monasterevin in County Kildare. The most notable thing about the family at this stage was that John Locke had married Jane Smithwick from the well-known Kilkenny brewing family. Because of this connection the Lockes continued to buy their yeast from the Smithwicks brewery in Kilkenny.

By the mid-1840s the demand for whiskey had recovered a little and John Locke took out a 999-year lease on the distillery, which included a mill. lt is evident from the earliest surviving business records (which date from the late 1840s) that sales of grain, meal and malt were almost as important to the business as sales of whiskey. The first entry in this ledger records the sale of a consignment of oatmeal for the Tullamore workhouse.

The rise of the Locke family

The social status of the family rose dramatically after they arrived in Kilbeggan. John Locke established the Kilbeggan Races which was a good public relations exercise as nothing drew such large crowds from all walks of life. The strong associations between drinking, racing and gambling were no less intense then as they are today.

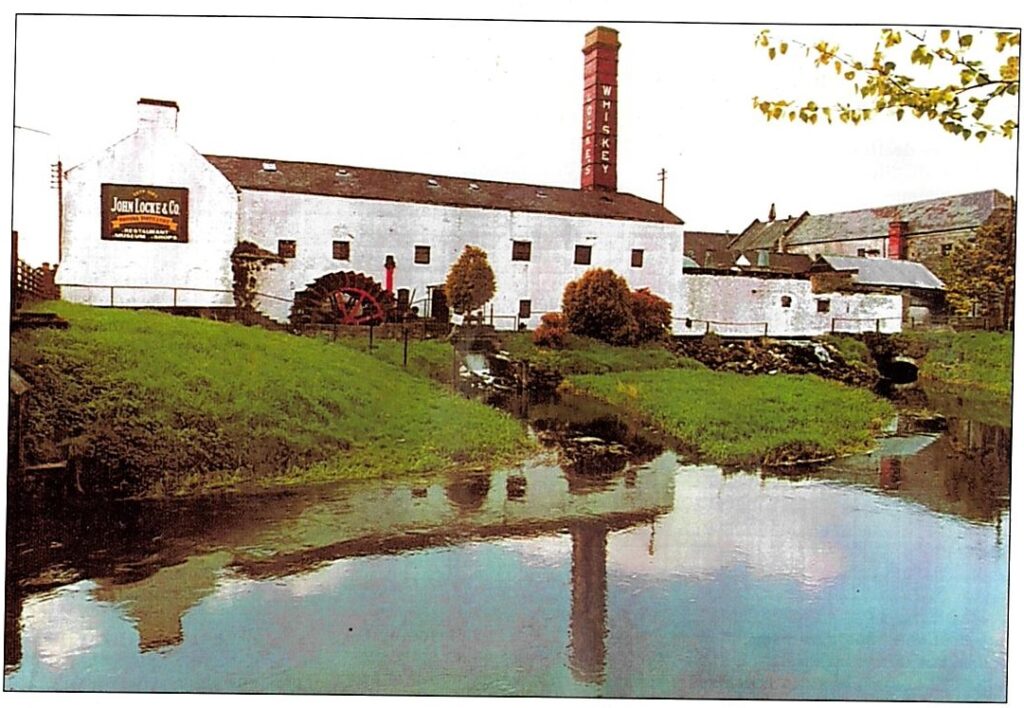

Shortly after having secured the property for the family business (which was to last three more generations), John Locke passed away in 1849. His son subsequently made an extremely good marriage into one of the wealthiest and most powerful Wexford Catholic families, the Devereuxs. The father of his bride Mary Anne, ran the Bishop’s Water Distillery (the largest in the southeast), her uncle was an MP and another uncle ran a huge shipping and malting business in Wexford town. The couple had five children; two subsequently became involved in the distillery, which was doing badly during the 1850s. Fortunately the Lockes also leased seventy acres Locke’s today with its water wheel and mill-race. of land in the vicinity of the town which supplemented their income during the lean spell.

Transport and market expansion

The bulk of Locke’s whiskey sales were made in Westmeath, Offaly and Roscommon. During the 1850s, the distillery was finding it increasingly difficult to maintain its market share in this region as larger midland and Dublin distillers were able to take advantage of the growing railway network to extend their markets. Many small distilleries with local markets were unable to adjust to the transitions brought about by the transport revolution and went out of business during this period. Locke’s, however, adjusted to the new circumstances and began to extend their market area during the 1860s thanks to a branch of the Grand Canal to Kilbeggan and the proximity of Horseleap railway station, only four miles away. Dublin became an important market and Lockes began to export to Manchester, Liverpool and Bradford where Irish migrants created a new source of demand.English exports accounted for over a fifth of total sales by the end of the 1860s and Dublin accounted for over 41%.

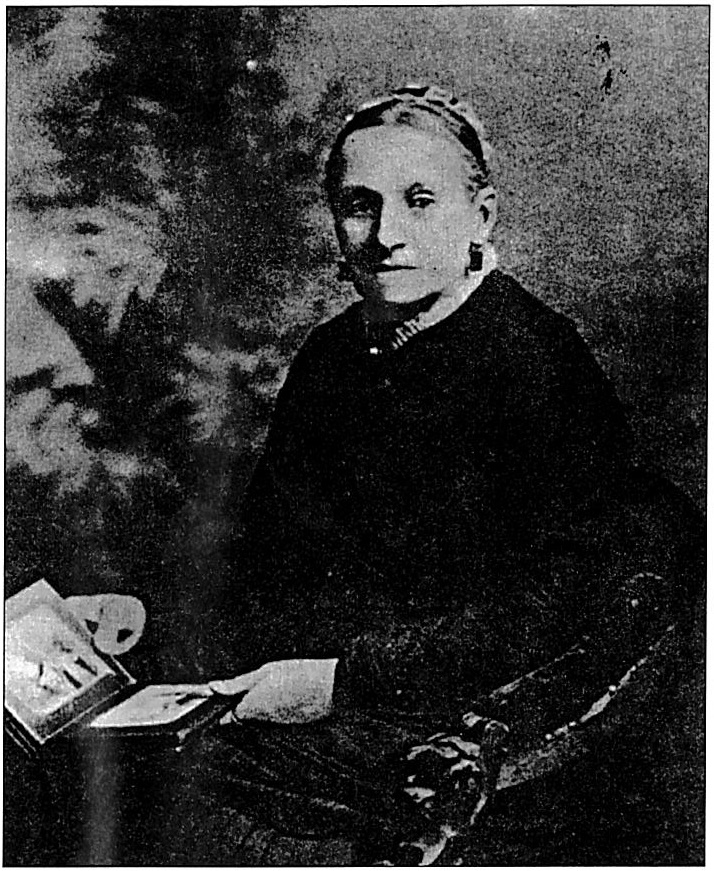

After the death of John Locke in 1868, the distillery was run by his wife Mary Anne until the 1880s when her two sons came of age and took over the concern. This was a major period of expansion and output rose from about 60,000 gallons in the late 1860s to 157,000 in 1886. The plant was upgraded and extended, a steam engine was installed and new buildings and offices were added. Lockes had its golden age during this period between the 1870s and the 1890s, supplying pot still whiskey to the southern Irish and English markets. The distillery also provided pot still whiskey to the northern Irish blenders who favoured the strong body and taste of the midland distilleries for blending, to give flavour to the more neutral- tasting grain spirit made by the large patent distillers based in Belfast and Derry.

In 1893 Locke’s was incorporated with a nominal capital of £40,000. A further £25,000 was raised from a public debenture. Thereafter accu- 48 HISTORY IRELAND Summer 1993 rate accounts were kept so that the books could be closed annually and dividends paid out. To raise working capital, the company got seasonal credit facilities from banks. The major credit requirement of the distillery was to purchase grain every autumn for which they ran up a large overdraft. As cheques and cash came in for whiskey sales over the rest of the year, the account was slowly brought back into the black.

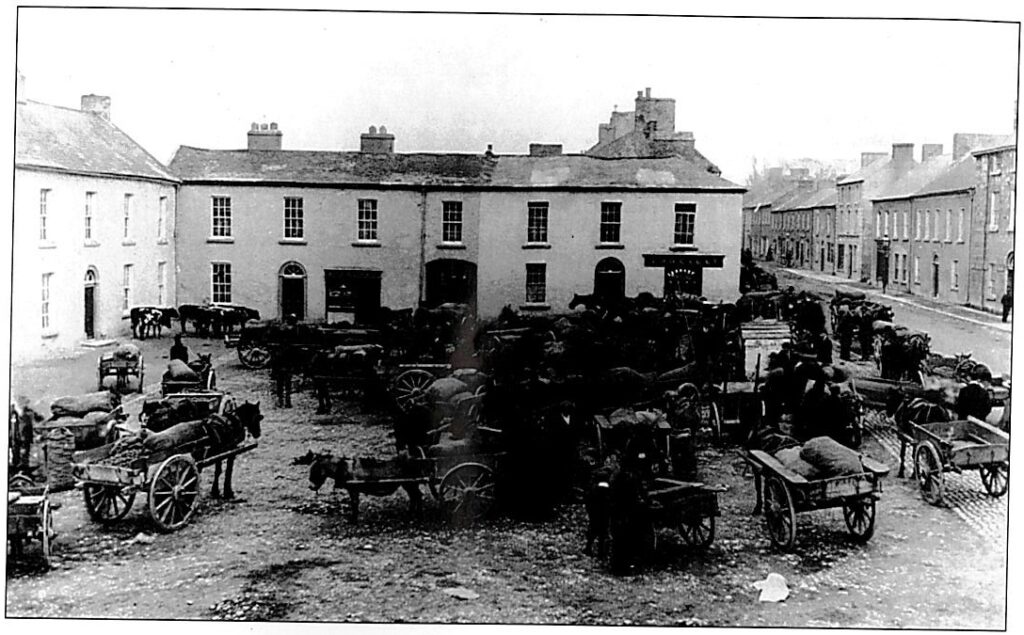

Locke’s purchased its grain locally, taking in about 40,000 barrels in 1891. This was delivered by farmers to the distillery yard in large sacks which were then hoisted into the warehouses. After the canal was built, the distillery used imported Welsh and Scottish coal to heat the stills. When distilling was in progress, huge plumes of black smoke could be seen rising from the distillery chimney; when certain weather conditions prevailed, the whole town was enveloped in smog.

When the distillery was in peak production, Lockes employed up to 120 people. Distilling is highly seasonal as the warm months are unsuitable for malting and fermentation. Employment therefore slackened considerably during the summer months; many of the workers got work taking in the harvest, some working on Locke’s farm; others found employment cutting turf on the local bogs.

Primitive techniques

Despite significant improvements to the plant between the 1860s and 1890s, distilling techniques remained fairly primitive until after the seco)ld world war. Until then, the head distillers were always recruited and trained within the distillery. Rule-of-thumb methods passed down by previous generations continued to be the guiding light of distilling practises and these remained relatively uninformed by progress in the sciences. When an outsider was first appointed to the position of head distiller in 1949, he was shocked to find wort and wash being pumped around the distillery in open troughs so that wild yeast and mill dust got into the liquid. This made fermentation unpredictable; the old hands argued that it gave character to the whiskey.

Unconventional conjugal arrangements

After the death of John Locke in 1868, the family moved to Ardnaglue, a country house outside the town with a tree-lined avenue, more in keeping with their rising social status. Mary Anne spent some of the profits from the spirits trade helping to establish the local Sisters of Mercy convent. The nuns are no longer keen to acknowledge the Locke connection as subsequent generations were somewhat less pious and devotional than Mary Anne. They took much less interest in church affairs and paid little heed to the conventional conjugal arrangements which the local clergy sought to enforce among their congregation.

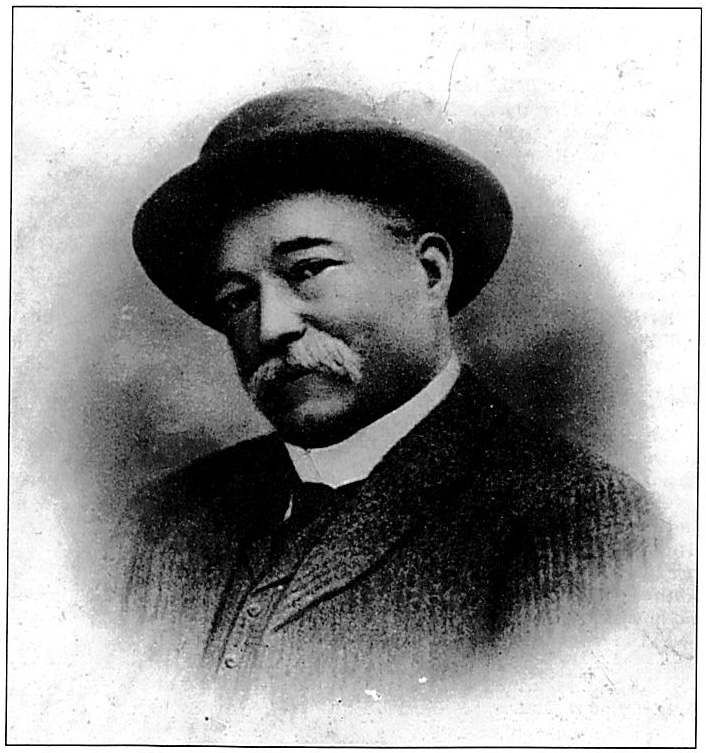

John Edward Locke took over the management of the distillery in the 1880s with his younger brother, James Harvey. In 1890 he married Mary Edwards (aged only seventeen) who became known as Muds Locke because of her hunting exploits. She had two daughters by him, Sweet and Flo, but the marriage did not last. Following a number of affairs with other gentlemen in the area, John Edward threw her out of the house and sued for divorce. A settlement of £600 was made in 1896 and Muds and the children moved to a fine house in Ballinagore, where she continued the hunting life. Muds worked for the Red Cross in France during the war and subsequently became the commandant of the Red Cross Hospital in Mullingar. The connection with the British war effort and the British army remained strong in the family; both Sweet and Flo married British army men whom they presumably met within Westmeath hunting circles. John Edward continued to live a somewhat more spartan existence in the old family dwelling beside the distillery where he kept a close eye on the day-to-day running of the business. His meals were prepared by his house keeper, Miss Cranley. An ex-employee of Locke’s, whose father had been John Edward’s batman, remembered John Edward sitting down alone to have his Christmas dinner, which consisted of two miserable looking herrings.

James Harvey Locke remained at Ardnaglue, leading a somewhat more stylish existence; after his mother’s death, the house effectively became his country seat. He was an avid huntsman, keeping his own pack of harriers. He maintained a racing establishment at the Curragh where many races were won in the Locke colours. He also rode many winners locally at the Kilbeggan Races and played polo in Mullingar. (the Lockes also established a cricket club in Kilbeggan). His sporting predilections and social life were quintessentially British. James Harvey never got married but had a long-standing love affair with Muds’ sister, Florence, to whom he left the farm at Ardnaglue.

Decline

The distillery yielded handsome dividends of up to 15% until the end of the century when the market for Irish pot still whiskey began to decline. A brief recovery during the first world war was followed by collapse and the distillery was forced to close down between 1924 and 1931. The two old Locke brothers died in the 1920s and responsibility for running the concern fell largely into management hands. After the breakdown of her marriage in the mid- 1920s, Sweet eloped with the master of the Westmeath hounds, a dashing young Scotsman. They married and when she returned to Ireland they decided to live in Mallow where the hunting was good and Kilbeggan and its clergy (who disapproved of her second marriage) were far away.

Left to their own devices, the management presided over a minor recovery in the 1930s. But during the second world war (when whiskey was in short supply), they began to operate a major illicit operation, plundering the distillery stocks which was blended with raw spirit straight from the stills. This lethal cocktail was ferried to the west of Ireland on a truck which left the distillery late at night. Locke’s still has a bad reputation in the West from this period. Small fortunes were made by the management who were involved in this illicit trade.

The Locke’s scandal and Dev’s gold watch

After the war, Sweet and Flo decided to put the distillery on the market. A syndicate put in a bid of £305,000 which was accepted. It included a Swiss businessman called Eindiguer, a Clonmel solicitor named Morris, and an English crook named Maximoe all of whom had previously been involved in a hare-brained scheme to introduce greyhound racing to Switzerland. The aim of this rogues’ gallery was to acquire the distillery stocks of 60,000 gallons for £305,000 and sell it off on the English black market for £11 a gallon. Auctioneers Stokes and Quirke were hired to secure the deal. Quirke was a Fianna Fáil senator and he hoped, through his influence on the governing party, to secure an increase in the distillery’s export quota to com’ plete the scam. Eindiguer was advised to give Taoiseach De Valera a Swiss gold watch to make this task easier.

The management at Lockes were displeased by the prospects of this impending sale, as they would lose control of the distillery, which was the goose which had laid their golden egg. So they broke the news to Oliver J. Flanagan, then an up-and-coming TD, who raised the matter in the Dail. Soon half the country was talking about Dev’s gold watch and a shady deal involving Fianna Fáil, bribery, corruption and (worst of all) foreigners. · An election had already been called for February 1948 so the whole saga which became known as the ‘Locke’s Scandal’, took on a very high public profile. Dev called a Tribunal to save the government’s ailing reputation. Although it officially cleared members of the government of any personal involvement in illegal activities, the public remained unconvinced. The scandal galvanised anti-Fianna Fáil support they lost the election, which ed to the first inter-party government.

The scandal ruined the goodwill of the company so the owners decided to try and turn the business around. The daughters of Flo had married into the McCormack and Murphy families (of singing fame and Independent Newspapers respectively) and members of these families were called onto the board. New staff were appointed and the plant which was now in appalling condition was overhauled. The company, however, was chronically short of working capital and it was also unable to increase its export quota. But the straw that broke the camel’s back was the budget of 1952 which raised the duty on spirits dramatically. This led to a decline in whiskey consumption so publicans cut back on the less advertised brands like Locke’s. Stocks built up in the warehouses as sales decreased, and distilling ceased in Kilbeggan in 1953.

To stay in business, the company had to increase its liabilities to the Provincial Bank; the overdraft rose to £67,000. There were no prospects of calling in a partner as the company’s reputation had become so tarnished by the scandal. Some last ditch attempts were made by Count Cyril McCormack to recruit partners in America but businessmen there were no more inclined to get involved than their Irish counterparts. With no prospects of a recovery, the bank decided to call in the receiver in November 1958 to recoup some of its losses. After two hundred years in operation, the distillery closed down and over the next decades an atmosphere of decay began to set into the old buildings.

Reincarnation

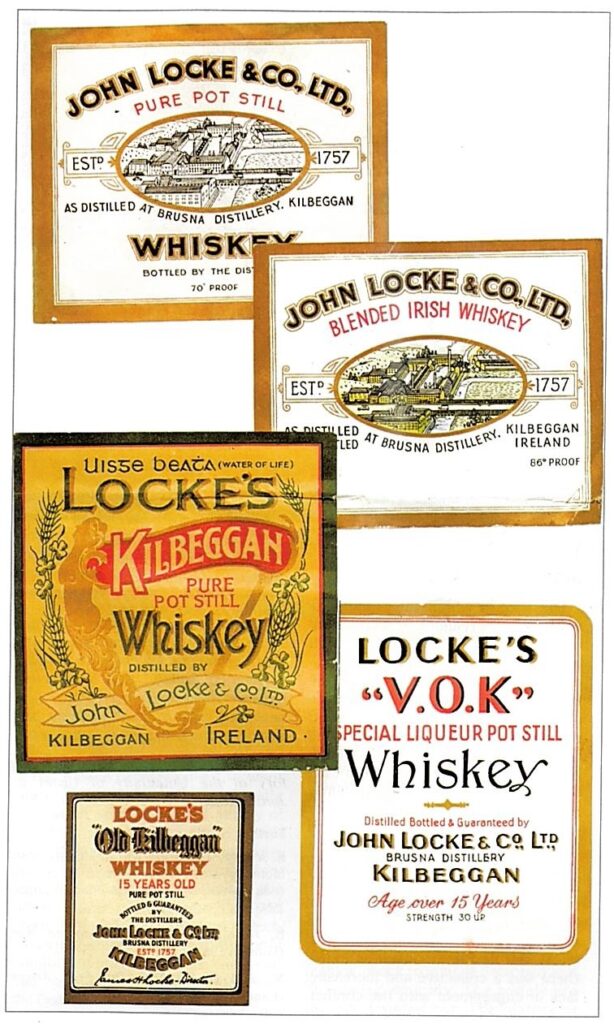

Kilbeggan’s associations with the distilling industry have however, recently been re-established by Cooley Distillery Plc. Cooley now have more spirits in the old warehouses in Kilbeggan than at any time in the distillery’s history. Locke’s whiskey has already been relaunched on the international market and Cooley intend to market it more extensively at home in the near future. So the tradition lives on.

Andy Bielenberg is a Junior Research, Fellow at the Institute of Irish Studies, Belfast.

Further reading:

A. Bielenberg, Locke’s Distillery; a history (Dublin 1993).