By Joe Culley

@TheRealCulls

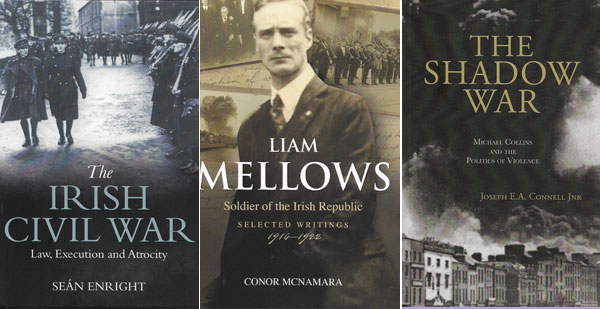

In The begrudger’s guide to Irish politics, Breandán Ó hEithir, while discussing the executions of the Four Courts prisoners during our brief but vicious Civil War, says of Dick Mulcahy: ‘It was public opinion, fed on rumours, that dubbed him “Dirty Dick” and the cry “Seventy-seven” followed him all through his political life’. That figure of 77 passed into folklore but, as Seán Enright details in his highly readable The Irish Civil War: law, execution and atrocity, the actual number of executions carried out by the nascent National Army was 83.

Enright’s central thesis is that in the autumn of 1922 ‘the usual separation of powers between those who tried criminal cases and the Executive had evaporated’, and ‘power now lay with General Mulcahy and the Army Council’. He suggests that the growing economic crisis for the fledgling state helped push the idea that executions were necessary and that the National Army should be given special powers. The murder of a TD, Seán Hales, in early December upped the ante radically, and the immediate, retaliatory killing of the Four Courts Four set an ugly precedent. Of those particular executions, Enright says: ‘The weight of academic opinion is that the legal reasoning of the Master of the Rolls (who justified the decision) was poor’.

Enright details the many botched executions by hesitant soldiers—‘… soon the National Army was billing the state for whiskey for the firing squads’—and points out that ‘To be tried for one reason and executed for another would become a common scenario during the war’. The book will be popular with both the general reader and the specialist, and is sure to stir up a debate two years ahead of the centenaries of its events.

One of the Four Courts Four was Liam Mellows, who is the subject of Conor McNamara’s equally fine Liam Mellows, soldier of the Irish republic: selected writings, 1914–1922. While this is not a straightforward biography, McNamara opens with an excellent synopsis of his subject’s life. I was surprised to learn just how miserable a time Mellows had during his four years in the United States following the Rising.

McNamara writes: ‘This collection of writings is not a coherent body of work left by Mellows with the intention of creating a political legacy or justifying his actions, rather it is the disparate public and private utterances of a young man who lived an itinerant life during a time of rapidly changing political realities’. Mellows was, according to McNamara, an ardent Catholic, a traditional physical-force republican and a ‘haunted soul racked with self-doubt’. (By the way, McNamara sets the number of executions at 81, not the 83 of Enright. I’ll leave it to the experts to argue that point.)

In his newest publication, The shadow war: Michael Collins and the politics of violence, Joe Connell takes an extensive look at the strategies, both political and military, that underlay the guerrilla insurgency of the War of Independence, and examines how those strategies were adopted and refined later by other independence movements.

In his wonderful Irish cinemas: a history in photographs, Jim Keenan tells us about the often-notorious Phoenix Picture Palace, or the ‘Feeno’, on Ellis Quay in Dublin, which was, he says, the capital’s first purpose-built cinema. ‘When being interviewed for an usher’s job at the cinema, candidates were often asked if they could swim. The question was posed because the management knew (from past experience) that ushers were quite likely to end up in the nearby River Liffey during the course of one of the many fights that occurred there.’

Keenan’s handsome coffee-table book is full of such anecdotes to accompany the many fine images of cinemas now mostly closed or demolished. In their heyday of the mid-twentieth century nearly every town had its cinema, many built during the art deco period of the 1930s. Curiously, the IRA of the time took an inordinate interest in the cinemas, either using them as ATMs for armed robbery or setting a few ablaze for perceived crimes of cultural imperialism. Many of the buildings have since been put to different use: one is now a Sikh temple.

Another coffee-table production—though at the higher end of the table (€35)—is the gorgeous Ireland’s court houses, from the Irish Architectural Archive. It is (as it says itself) ‘a lavishly-illustrated, wide-ranging and authoritative exploration of the architecture of court houses in Ireland from the late 17th century to the early 21st century’. There is also a focus on recent restorations and new constructions. It includes two illustrated gazetteers, the first a selection of significant houses, the second an alphabetical one of, it seems, every courthouse in the land, each with its own text on design and history of use. Impressive work.

Another illustrated hardback is also a little gem: Mary Ward’s Sketches with the microscope in a letter to a friend, which first appeared in 1857, has been superbly reproduced by Brosna Press for the Offaly Historical and Archaeological Society. Ward was a cousin of the earl of Rosse, of Birr Castle and the great telescope fame. Born in 1827 on an estate outside Ferbane, she received no formal schooling but matured into a respected scientist and renowned artist/illustrator. When she was eighteen she was given one of the earl’s state-of-the-art microscopes, and her scientific investigations began in earnest. The illustrations are wonderful. This compact (5in. x 6½in.) reproduction includes a fine introductory essay by John Feehan on Ward’s scientific and artistic work. Unfortunately, Mary Ward’s other claim to fame is rather more ignominious: she was killed in 1869 in what is considered the world’s first motor accident when she fell from a road locomotive invented by the earl.

One last nicely illustrated hardback is Ray Rooney’s The spirit of the reels: the story of the famous Liverpool Céilí Band. The band, which had strong links to Kilmihil in County Clare, was good enough to win the All-Ireland Fleadh Cheoil.

The 2019 edition of the Donegal Annual includes an essay on the assisted emigration scheme from Aranmore in the 1880s organised by the English Quaker James Hack Tuke, who, as we mentioned in HI 26 (6) (Nov./Dec. 2018), also ran the scheme in Connemara. Also in the volume are essays on the painter Robert Taylor Carson, on the last elected MP in Westminster and on the effect on Buncrana of a royal visit in 1903.

Finally, a quick mention of the Voices of the Troubles Oral History Collection, an audio archive which chronicles the lives of a border community during 1968–98. The 85 interviews can be heard on the Cavan County Library website.

Seán Enright, The Irish Civil War: law, execution and atrocity (Merrion Press, €18.95 pb, 200pp, ISBN 9781785372537).

Conor McNamara, Liam Mellows, soldier of the Irish republic: selected writings, 1914–1922 (Irish Academic Press, €18.95 pb, 230pp, ISBN 9781788550789).

Joseph E.A. Connell Jnr, The shadow war: Michael Collins and the politics of violence (Eastwood Books, €18.99 pb, 356pp, ISBN 9781916137509).

Jim Keenan, Irish cinemas: a history in photographs (Picture House Publications, €25 hb, 140pp, ISBN 9780955068393).

Paul Burns, Ciaran O’Connor and Colum O’Riordan (eds), Ireland’s court houses (Irish Architectural Archive, €35 pb, 380pp, ISBN 9780995625815).

Mary Ward, Sketches with the microscope in a letter to a friend (Offaly Historical and Archaeological Society, €20 hb, 58pp, ISBN 9781909822146).

Ray Rooney, The spirit of the reels: the story of the famous Liverpool Céilí Band (RayRoo Press, €25 hb, 200pp, ISBN 9781916188501).

Seán Beattie (ed.), Donegal Annual/Bliainiris Dhún na nGall (County Donegal Historical Society, €25 pb, 135pp, ISSN 04162773).