By Declan Keenan

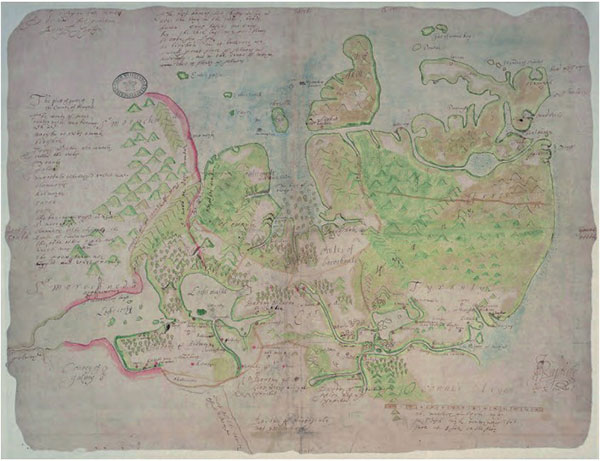

For generations (from the mid-fourteenth up to the close of the sixteenth century) the Gaelicised Bourke septs of Mayo elected their chieftain, the MacWilliam Íochtair (the premier lord in Mayo), in the Gaelic manner at their adopted inauguration site of Rausakeera, in the barony of Kilmaine. Indeed, Rausakeera, a bivallate earthen fort (perhaps part of or central to a preceding ríocht or lordship), appears to have been adopted as a ceremonial site by the Bourkes in the fourteenth century as a place, as Elizabeth Fitzpatrick suggests, ‘which might lend some antiquity and gravitas to their past’. It is conceivable that between ten and twenty such inaugurations could have occurred at Rausakeera from the mid-fourteenth century up to the close of the sixteenth century. This article explores one such inauguration in December 1595, which is often briefly mentioned with respect to the Nine Years War but rarely further explored.

Composition of Connaught

These long-standing inauguration traditions were to come to an eventual end (officially, as per English law) via the instrument of a 1585 tax agreement, known as the Composition of Connaught, which served to remove the customary exactions due to the magnates of the province, to abolish traditional titles of chieftainship (and inauguration practices along with it) and to signal the commencement of English law within the province. Indeed, the Composition had far-reaching consequences for the Gaelicised and Gaelic septs of County Mayo, as it affected the traditional methods of succession and abolished the prized title of MacWilliam Íochtair.

The adoption of English law in relation to succession or inheritance was significant. Under the Composition, primogeniture was to replace the traditional Gaelic practice of tanistry and election, long since adopted by the Bourkes of Mayo. Where once the title could be contested by any senior male member of one of several leading Bourke septs, under the Composition the title and associated lands, power and benefits were transferred to the eldest son of the reigning title-holder at the time of the Composition.

In response to their impoverishment arising from the conditions of the Composition, many of the disaffected Bourke septs revolted against the Crown in 1586. Further unrest in late 1588 was related to the arrival of remnants of the Spanish Armada, driven onto western coasts by poor weather. Some of the septs within the western baronies harboured Armada survivors, whose presence led to open rebellion against the Crown in 1589; the Bourkes once again defiantly elected a MacWilliam at Rausakeera. Therefore, between the Composition (1585) and the opening of the Nine Years War (c. 1593), many of the Bourke septs were ill disposed towards Crown influence in Mayo.

Nine Years War

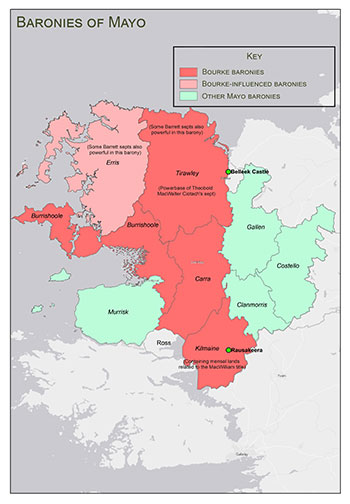

To aid their cause in the Nine Years War, Hugh O’Neill and Red Hugh O’Donnell sought to create a confederacy of Irish lords (both Gaelic and Gaelicised), not only to form a national movement but also to relieve pressure on their own territories. To this end, both O’Neill and O’Donnell forged alliances with Gaelic chieftains such as Feagh MacHugh O’Byrne, amongst others, but occasionally they also sought to install leaders in certain septs to ensure support. As FitzPatrick suggests, internecine disputes were ‘exploited by both leaders to nominate amenable candidates’. Indeed, by 1595 O’Donnell had made several incursions into Sligo, Mayo and Connacht in general, and may have felt confident in his power to oversee the nomination of amenable Connacht lords.

The 1595 inauguration

The Gaelic confederacy may have seen advantages in re-establishing the MacWilliamship in Mayo, particularly given the various events following the Composition. Although the title MacWilliam Íochtair had been officially abolished for some ten years by this stage, it likely remained in memory a prized position. To this end, Red Hugh became directly involved in Mayo politics and set about initiating an ‘untraditional’ inauguration at the ‘traditional’ Rausakeera site in 1595. The inauguration is described in detail in Beatha Aodha Ruaidh Uí Dhomhnaill (written by Lughaidh Ó Cléirigh). In this account O’Donnell appears as overlord or conqueror, holding sway over a procedure that was traditionally undertaken by what was previously a strong and independent lordship in its own right:

‘There came to that same meeting, like the rest, to Ó Domhnaill, the chiefs and barons of the country … It was by consultation among these and by election that a chieftain used to be inaugurated …, and he was called by the title of MacWilliam on the rath of Eas Caoide, and it was MacTibbot used to proclaim him. When all these nobles had assembled …, Seán Óg O’Doherty formed (as he was ordered to do) four lines of troops back-to-back encircling the liss and the warrior-fort. Eighteen hundred of his soldiers and mercenaries around the royal rath were the first company; O’Doherty himself and O’Boyle, Tadhg Óg, with the infantry of Tír Conaill outside them, in the second circle; the three Mac Suibhnes with their galloglasses outside them; the men of Connacht with their muster outside them all; Ó Domhnaill himself with his chiefs and nobles in a close circle on the rampart of the rath, and no one of the nobles or gentlemen dared approach him in the rath but whomsoever he ordered to be called to him in turn … He called to him the barons and chiefs of the territory … to ask them one by one which of the nobles he should appoint to the chieftaincy … MacDomhnaill, MacMorris, and Ó Máille said … it was right that the senior, William Burke, should be styled chief, as their custom was to appoint the elder in preference to the younger. MacCostello and MacJordan said that it was fitting that Tibbot, son of Walter Ciotach …, should be styled chief, for he was strong and vigorous by day and by night at home and abroad, whether he had a few or had many with him. When Ó Domhnaill had pondered well, he resolved in the end to confer the chieftainship … on Tibbot, son of Walter Ciotach, and he ordered MacTibbot to proclaim him Mac William. This was done …, though there were others of his race older in years and greater in repute than he.’

Indeed, in his description Ó Cléirigh provides a hint as to the original nature and protocol of the Bourke tradition—‘by consultation among these and by election that a chieftain used to be inaugurated over the country’. It is clear, however, that O’Donnell had sidestepped the traditional proceedings of a Bourke inauguration. Given the military might present and their deployment around the site, there was to be no ‘second-guessing’ of O’Donnell’s decision. As described above, the fourth ring around the rath was the ‘men of Connacht’, i.e. the traditional electors and claimants, potentially limiting the access of the Bourke septs and contestants to the proceedings. It was probable that MacTibbot had little option but to proclaim Theobald MacWalter Ciotach as chieftain. Furthermore, it is conceivable that the selection may have been pre-arranged.

Needless to say, O’Donnell’s marshalling of a long-standing rite within a traditionally independent lordship was met with considerable and immediate opposition. Many septs considered that there were more deserving candidates among their own, but there were perhaps several reasons why O’Donnell supported the suit of Theobald MacWalter Ciotach and which might have provided the confederacy with advantages if the appointment had held:

- Theobald’s powerbase and lands were in the barony of Tyrawley, with his centre at the castle of Belleek. These lands in the north-east of the lordship bordered the lands of Sligo, an area where O’Donnell claimed rights of overlordship. As such, Theobald’s centre of power may have provided a bridgehead for the confederacy over the River Moy into Mayo.

- Despite having effectively seized the chieftaincy, Theobald had a reasonable pedigree for the position. He was a leading scion of the Sliocht Ricard Bourkes; his grandfather, Sir John, and great-uncle, Richard FitzOliverus, had held the MacWilliamship in preceding decades.

- In addition, Theobald had been imprisoned in Athlone Castle by the Crown in 1593. Considering O’Donnell’s own treatment and imprisonment as a youth by the Crown, it may not be surprising that he felt compelled to support Theobald.

A brief description of the inauguration is also provided in the Annals of the Four Masters (AFM). The AFM also indicates ‘the summons of O’Donnell’ to Rausakeera, and his selection of Theobald based on his being the ‘first to come over to him’ and ‘in the bloom of youth’.

The appointment backfired on O’Donnell almost immediately. Indeed, he travelled back to Tyrconnell with several of Theobald’s competitors as hostages. Although Theobald had a reasonable pedigree, O’Donnell had selected one of the least eligible in accordance with the custom of the Bourkes (on account of his age). Despite O’Donnell’s attempts to potentially ‘secure’ the territories of Mayo, Theobald was never to gain popular support from within the Bourke septs over the course of the war. In fact, the affair at Rausakeera merely served to bolster an almost constant opposition to O’Donnell’s MacWilliam and diminished the status of the MacWilliamship.

Impacts of the inauguration

In the short term, O’Donnell had effectively alienated the larger portion of the Bourke septs from the Gaelic confederacy and pushed them into making a choice between the Crown and O’Donnell’s overlordship in the form of an unpopular MacWilliam. A potential deficit for the confederacy was the loss of access to many fighting men within the Bourke territories (who might once have been willing adherents), including one of their emerging and most effective leaders, Theobald ne Long (Theobald of the Ships). Theobald ne Long Bourke, a man of means and ability on both land and sea, the son of Grace O’Malley and Richard an Iarnainn Bourke (a former MacWilliam Íochtair), was pushed beyond the reach of the confederacy. He had reportedly access to three galleys and a mini-navy comprising of hundreds, a rarity in Gaelic Ireland. Theobald ne Long took it upon himself to drive MacWilliam out of Mayo upon almost his every incursion. As such, the MacWilliam remained in a weak position, met rarely with success, and was continually propped up by hundreds of O’Donnell’s own men over the course of the war. Each MacWilliam incursion into Mayo was met with a swift retaliation, and several times MacWilliam was driven back into Tyrconnell, only to be reinforced and sent back. O’Donnell continually made use of Mayo as a decoy to divert Crown forces and attention from other locations. Generally, most of the Bourke septs objected to the continual exploitation and depletion of their lands and livestock, and saw themselves as pawns in the confederacy strategy. At this stage Mayo was generally under the control of Theobald ne Long.

Ultimately the nomination could be described as a strategic misjudgement, and only served to reduce O’Donnell’s influence in Mayo as the war progressed. Furthermore, his selected MacWilliam was not as strong a military leader as his sponsor. The entire lordship, which was originally disaffected with Crown government, could possibly have fallen into O’Donnell’s hands with greater ease had a more sensitive selection taken place, and along with it unopposed access into Mayo. This, however, was not to be. It also possibly deprived the northern confederacy of access to additional fighting men within the Bourke territories, some of whom opposed O’Neill and O’Donnell at the Battle of Kinsale (the decisive battle in the war), under the leadership of Theobald ne Long. Moreover, the policy may have deprived the northern confederacy of potential safe anchorages within the Bourke territories, which might have been more suitable than Kinsale.

Overall, the sub-plot suggests that O’Donnell may have been a greater military mind than a strategic planner—or perhaps the sub-plot was so minor as not to concern him. In literature on the Nine Years War, the 1595 inauguration at Rausakeera tends to be underplayed or forgotten; had a more amenable approach been adopted, however, the consequent winning over of most of the Bourke septs would have conferred additional advantages on the northern confederacy.

Postscript

As for O’Donnell’s MacWilliam, he, like O’Donnell (in spite of later intrigues with Captain Thomas Lee), travelled to Spain, arriving in July 1603. He died there in 1604, never to return to his patrimony, but his son, Don Balthazar or Walter, was knighted by Philip III of Spain as a Knight of Santiago in 1607. Interestingly, there is record of a decree confirming the Spanish title ‘Marques de Mayo’ to ‘Baltasar de Burgo Macuillburgk’ on 21 July 1627.

Declan Keenan is a Transport Infrastructure Ireland engineer with an MA in History.

Read More

IRISH CHIEFS’ AND CLANS’ PRIZE IN GAELIC HISTORY 2022

Further reading

Beatha Aodha Ruaidh Uí Dhomhnaill, Corpus of Electronic Text Editions (CELT), UCC.

E. FitzPatrick, Royal inauguration in Gaelic Ireland c. 1100–1600: a cultural landscape study (Martlesham, 2004).

M.A. Freeman (ed.), The Compossicion Booke of Conought (Dublin, 1936).

H.T. Knox, The history of the county of Mayo (Castlebar, 2000).