By Julitta Clancy

‘What an effect might be caused in Ulster were some friendly advance to be made to her now—were the boycott to be called off and a real and lasting truce to be proclaimed? I verily believe that the one moment of all the centuries has been reached in which north and south might understand each other.’

(Belfast linen manufacturer, UUC member, November 1921)

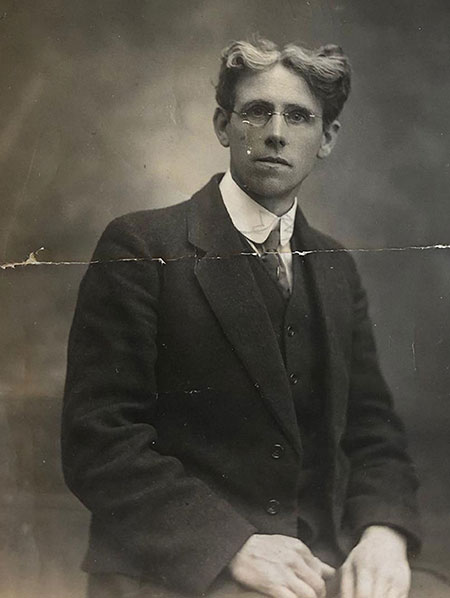

In November 1921 the focus in the Treaty negotiations in London turned to ‘Ulster’. The Northern Ireland government and parliament had been in operation since June and partition was an established fact, but the aspiration of ‘essential unity’ was central to the Irish position in the negotiations. While discussions centred on an ‘all-Ireland parliament’, and Lloyd George conferred with Sir James Craig, the Dáil cabinet and plenipotentiaries commissioned J.L. Fawsitt (1884–1967), adviser to Robert Barton, to proceed to Belfast to ‘enquire into and report on the economic conditions prevailing in the North … and to make soundings amongst the leading men of commerce in Belfast as to the conditions on which they would be prepared to advise their Government to throw in its lot, politically and economically, with the rest of Ireland’.

Recently recalled from New York as the Republic’s first consul-general to the USA (1919–21), and formerly secretary of the Cork Industrial Development Association, Fawsitt visited Belfast five times—from late November 1921 through the dramatic events of December and January. Alongside analyses of economic and industrial conditions, his four reports to cabinet include observations on the changing political views of some leading Belfast businessmen—attitudes to an all-Ireland parliament and unity—before and after the signing of the Treaty on 6 December. From initial enthusiasm, the reports trace the ‘somewhat sobering down’ of their views in response to ‘extremist speeches’ in the Dáil. On the fourth visit Fawsitt carried a message from President Arthur Griffith to the Northern Ireland government, while the fifth and final visit was to relate to Bishop McRory ‘the circumstances surrounding the decision of the Cabinet of Dáil Éireann to lift provisionally the Belfast Boycott’.

Although the reports are in the National Archives and National Library, the story of this historic initiative—later overtaken by north–south tensions and the divisions of the Civil War—has remained largely unexplored. Newly discovered material, found by the Fawsitt family in the old farmhouse loft in Manch, West Cork, in 2018, has now shed further light on the mission and the personalities. Scattered among thousands of documents crammed into tea chests were Fawsitt’s own records of the mission—letters, reports, diaries, expense accounts and a notebook listing interviewees and the main points discussed. This material, along with the remainder of the Fawsitt Papers at Laurelmount, Co. Cork, was arranged and listed by the writer prior to their donation by the family to Cork City and County Archives in 2019, and forms the basis for the following chronological account.

First visit, 24 November–1 December 1921

‘The time of my visit was marked by the imposition of Curfew on Belfast; the appearance of military in war accoutrements in large numbers and armoured cars on the streets, by shootings and bombings in the business heart of the city, by the return of Sir James Craig from London, and by the discussion in the Belfast Parliament on the negotiations towards a political settlement.’

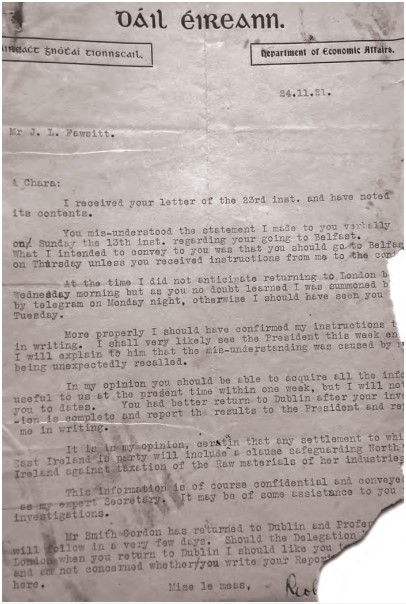

Briefed on Sunday 13 November at meetings in the Mansion House with ‘Barton, Childers, Cosgrave, etc.’, and later with de Valera, Fawsitt proceeded to Belfast on the 24th, taking the 3pm train with Professor R.M. Henry of Queen’s University and staying at the Royal Avenue Hotel (the street was the scene of an IRA attack on a crowded tram that evening). He spent the week following up contacts, holding interviews and attending to correspondence, including from Seán Milroy in London, relaying Robert Barton’s instruction to ‘report the results to the President [de Valera]’, which occasioned an overnight return to Dublin on Sunday 27th.

Contacts and interviewees

‘I approached and conferred with many men representative of the economic life of the city. These included shipping, linen, tobacco, biscuit, whiskey, timber, engineering, flour and other industrial interests; also, representative solicitors, accountants, insurance and banking officials. Many of those interviewed were prominent members of the Ulster Unionist Council and of the Orange and Masonic Orders. In addition I conferred with the Catholic Bishop and certain Catholics directing large businesses in Belfast and district … I was careful to explain … that though I was attached to the Ministry of Economics of Dáil Eireann, my visit on this occasion was private and unofficial.’

Fawsitt’s key contact in Belfast was Alec Wilson JP, Protestant Home Ruler and accountant at Harland & Wolff, who, like Fawsitt, had long been involved in the promotion of Irish industries. Wilson introduced him to R.V. Williams (the poet ‘Richard Rowley’), linen manufacturer and UUC member. Further introductions were provided by Thomas Burns (accountant) and J.J. Cosgrove (potato exporter), including to a gentleman who occupied ‘a very important position in the Corporation’. Fawsitt’s diary records meetings with Gordon Dickson (solicitor), Sam Kelly (coal exporter, shipowner and UUC member) and Joshua Cunningham (Northern Whig family), while his notebook also lists J[ames] Brady JP (linen finisher), R[aymond] Burke (son of Sir John Burke, shipbroker), W. Heney (linen merchant), J. Hoey (of Bushmills), P[atrick] O’Driscoll (banker), Wellwood (timber merchant), J.J. Kelly (insurance), and the aforesaid Prof. Henry and Bishop McRory.

First report to cabinet (3 December)

Fawsitt departed Belfast on 1 December and proceeded via the 9.15pm North Wall Dublin boat to Holyhead. Arriving in London at 9am on the 2nd, he found that ‘Barton, A.G. [Arthur Griffith] and others had returned to Dublin’. Here he completed his first report, comprising analyses of economic and industrial conditions alongside observations on the views of industrial leaders: ‘The war and its aftermath of unsettled political and economic conditions’, the ‘loss of British and oversea markets, the crushing impost of British taxation, and the fickleness of political allies in Great Britain’ had ‘unconsciously occasioned a searching into the soundness of the political faith heretofore adhered to so devotedly’.

Fawsitt concluded:

‘Not one of the many Belfastmen whom I interviewed individually expressed any “die-hard” spirit. All expressed grave concern for the future of the country as a whole, all desired a political understanding and settlement with the rest of the people of Ireland, and all felt that the best and most immediate way to secure this was by means of conference in Ireland with Irish national leaders.’

They were, he believed, ‘of sufficient weight both in financial and political circles to secure for whatever views they may advance a respectful and serious consideration in the quarters indicated’.

Second visit, 13 December 1921

Writing on 7 December, Alec Wilson welcomed the ‘extraordinary success’ of the negotiations: ‘I am filled with admiration for the entire Treaty document … the most important event in Irish history for many centuries … a real charter upon which the wider liberties can be built; a contribution-making Treaty which will be a permanent part of our national life for generations to come’.

R.V. Williams wrote excitedly from Ormeau Avenue on the 12th: ‘Things have changed since I saw you in Belfast, and events have travelled rapidly. I have been astonished to find, since the Treaty was published, how strong a feeling there is in the business community of Ulster … if the Dáil accepts the Treaty, Ulster will be ready to go into an Irish Parliament. There will be, of course, strong opposition from the extreme elements …’. He had ‘put together the nucleus of a businessman’s committee, to influence our government in the direction of making terms at once’.

Meeting again with the businessmen, Fawsitt reported that ‘one and all were ready to act on the Committee referred to … they but awaited the ratification of the Treaty by both Parliaments, to come together formally to take steps to make their views known to the Premier and Cabinet in Belfast’, adding that ‘in Orange circles it was reported to me that refusal by the Dáil to ratify the Treaty will be seized upon to press for wider powers for the Northern Parliament’.

He appended a statement by a UUC member setting out the assurances required: no taxes on raw materials or exports, ‘freedom of education from any kind of clerical control’, and guarantees that ‘there will be no attempt to make the Irish language compulsory in the schools, or that ignorance of that language will be a bar to promotion in the public services’. Above all, ‘let Sinn Féin assure Ulster that … there is no desire for conquest or ascendancy; that Ulstermen will be welcome to assist in the task of building up a new Ireland’.

In the event of the ratification of the Treaty, Fawsitt intended to go to Belfast to put together his ‘businessman’s committee’.

Third visit, 29 December 1921

During the Christmas recess, Fawsitt again met with the businessmen, this time at the ‘special request’ of Michael Collins. His report (31 December) noted that the Treaty debates had ‘sobered down somewhat their keenness on immediate action’ towards unity with the south. More than one of them referred to the ‘extremist’ speeches uttered in the Dáil. The ‘more liberal’ among them ‘felt some disappointment at the apparent hesitancy of the members of An Dail … to accept the terms of the Treaty in a spirit of goodwill … Practically, one and all of the Belfastmen told me that no progress towards a political settlement with the south could be attempted until the decision of An Dail was known, and a Provisional Government set up in the south under the terms of the Treaty’.

At an ‘informal meeting … all present were favourable to union with the south’. On ratification of the Treaty they intended to hold a formal meeting of the ‘Unity Committee’ and would then consider ‘approaching the Northern Premier and … suggesting to him the advisability of arriving at an understanding with southern Ireland’. They called for ‘a public statement by a responsible southern leader, along the lines of the declaration made by Minister Griffith’, which would ‘be timely and helpful to those working for unity and understanding in the north’.

Fourth visit, 11–13 January 1922

Following the ratification of the Treaty, the resignation of de Valera and the election of Arthur Griffith as president, Fawsitt travelled to Belfast carrying credentials from the new cabinet and a letter to the Northern Ireland government signed by Griffith. He approached UUC member Sam Kelly, seeking his aid in contacting the Northern Ireland cabinet, and later met with Wilson, Professor Henry and Bishop McRory. Having transmitted Griffith’s message to Minister for Labour John M. Andrews, Kelly brought back a statement setting out the position ‘towards union with the Irish Free State’: while ‘understanding and cooperation with the south is desired’, a change in policy was not warranted, and a ‘line of future political action’ would be presented to the UUC meeting on 27 January. Pending their decision, ‘the Ulster Cabinet will take no steps towards an immediate arrangement with the Provisional Government of the Irish Free State’.

Kelly undertook to discuss the matter with the ‘Unity Committee’ and to ‘take suitable action both with regards to the Northern Cabinet’s attitude, and to the … meeting of the Ulster Unionist Council of which all are members’. Back in Dublin that evening (13th), Fawsitt reported ‘to A.G. [Arthur Griffith] and M.C. [Michael Collins] on Ulster’; his awaited return was noted in the cabinet minutes.

Fifth visit, 25–26 January 1922

Following the first Craig–Collins Pact, Fawsitt was sent by Griffith to personally inform Bishop McRory of the circumstances behind the lifting of the boycott and, while there, he met up again with Sam Kelly. On 27 January the UUC rejected the proposals on the boundary that Craig had agreed with Collins and no further visits are recorded by Fawsitt. In February and March, as acting secretary in the Ministry of Economic Affairs, he went on three more ‘special missions’—to London and twice to Cork—and submitted expenses for all the missions in May. His last reference to the Belfast mission was on 26 September 1922, in the course of a long letter to President W.T. Cosgrave.

Julitta Clancy is an archivist and indexer, and a granddaughter of Judge Diarmaid Fawsitt.

Further reading:

B. Barton, ‘The Dáil Cabinet’s mission to Belfast, 1921–22’, in P. Bew et al. (eds), Northern Ireland, 1921–2021: centenary perspectives (Belfast, 2021).

J. Bowman, ‘Sinn Féin’s perception of the Ulster Question: autumn 1921’, The Crane Bag 4 (2) (1980–1) (Northern issue).

J. Clancy, ‘Treasures in the loft’, Ríocht na Midhe (2020).

F. Murray & E. Sagarra (eds), The men and women of the Anglo-Irish Treaty delegations 1921 (Cork, 2021).