By John Mulqueen

‘As we marched down Grafton Street calling out our message and asking for support, a few … decided to join us … The rest ignored us or patronisingly smiled at our foolishness … We were eventually met by a solid blue line of gardaí … I asked permission to protest formally at the embassy. Seconds later I was violently hurled through the air …’

Then ‘the strange animal sounds, the snarls, excited barks and whimpers … all so unexpected and unthinkable that it was hard to know what was happening’.

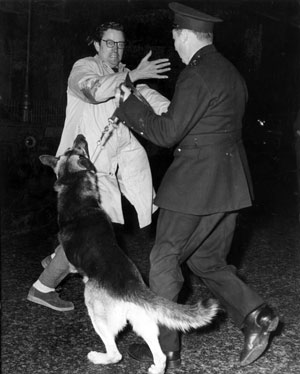

Noël Browne describes here an attack on him and fellow disarmament demonstrators on 23 October 1962 by Garda officers and their dogs in central Dublin. The placards held aloft during this impromptu protest against John F. Kennedy’s decision to confront Nikolai Khrushchev had a simple, if not simplistic, message: ‘Hands off Cuba’.

Browne, then an independent TD, and a few dozen others were brutally prevented from marching to the US embassy. Fearing a nuclear catastrophe, they wanted the US president to lift his blockade of Cuba, which prevented Soviet ships from landing on the Caribbean island. Five days later the Soviet leader blinked first. Khrushchev announced that he would not deploy nuclear missiles in Cuba in exchange for Kennedy’s promise that the US would not invade it. The Cuban Missile Crisis was effectively over, but for six days the world had come as close as it ever has to a nuclear war between the two Cold War superpowers.

If most people in Ireland had been less afraid during the crisis than many in, say, the US, it is safe to assume that they were not as nonchalant, or deluded, as Patrick McCabe’s character Francie in The Butcher Boy. While the other folks in McCabe’s fictional small country town saw it as the end of the world and sought divine intervention, Francie had his own ‘Wild West’ solution to the problem created by ‘these communists’: shoot them all. ‘I’m the man to do it. I’ll knock a bit of sense into them. Oho yes.’ But Francie did not have to put on his sheriff’s badge—‘Baldy Khrushchev’ and his gang had met their match this time. ‘Oh yes, yes indeed. They sure have! John F. Kennedy. I said it like John Wayne. John Ayuff Kennedy. Yup!’

ICONIC IMAGE OF IRELAND IN THE 1960S

The photograph (by Gordon Standing) of Browne, encountering the tough guys on the streets of Dublin with fear in his eyes, and the Garda dog became an iconic image of Ireland in the 1960s. Before the photographer captured the dramatic image, the animal briefly had Browne’s elbow in its mouth. Several of his fellow demonstrators—mainly students from Trinity College—were bitten by the dogs. The protestors’ statement for the US embassy pointed out the obvious fact that there could be no winner in a nuclear war, and added that if the Soviets wanted to have nuclear arms in Cuba they were doing the same as Kennedy and NATO in ‘nearly every country in Europe, from the Clyde to the Black Sea’.

In Ireland the advocates of nuclear disarmament were few in number, but in Britain it was different. The possibility of nuclear war spurred tens of thousands there to campaign for disarmament; at its 1962 peak 150,000 supporters of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) marched to the Atomic Weapons Establishment at Aldermaston.

LEMASS EVASIVE ON NEUTRALITY

Shortly after Khrushchev announced his historic compromise, opposition TDs questioned Seán Lemass in the Dáil on whether he would drop the state’s military neutrality in order to join the European Economic Community (EEC). Browne—dismissed as a ‘Red’ by the taoiseach’s Fianna Fáil colleagues—accused Lemass of attempting to involve the state in the Cold War by dumping ‘traditional neutrality’. Would he allow NATO bases in Ireland? Browne received a sarcastic answer: ‘Neither here nor in Cuba … Go back to Khrushchev and tell him.’ Lemass was being evasive here. In fact, he had been preparing the ground for a shift in the policy of military neutrality if this was required for EEC membership. ‘[O]ur desire is to participate in whatever political union may ultimately be developed in Europe. We are making no reservations of any sort, including defence.’ One of his ministers had earlier hinted that the government’s opposition to joining NATO—it necessitated recognising the partition of Ireland—had softened.

A military relationship with NATO members, of course, involved links to nuclear powers; therefore various disarmament groups, including Irish CND, highlighted the neutrality issue that had emerged around the bid to join the EEC. Browne argued that it had been ‘impossible’ to obtain ‘any categorical statement on the political and military implications’ of joining the EEC, and so the anti-NATO lobby called for a referendum to protect Ireland’s military neutrality. Those who opposed the possibility of Ireland joining a military alliance would ‘stand up and be counted’, an independent senator for Trinity College, W.B. Stanford, declared. Stanford—no ‘Red’—contended that there were ‘many serious-minded, well-informed and anti-communist citizens who would deplore our entering into any military bloc that involved the acceptance of nuclear armament’. Helen Chenevix, a lifelong women’s rights activist and a pacifist, drew attention to the failure of the government to provide information on the political—namely military—consequences of joining the EEC.

IRISH CND

Irish CND had been launched four years before, the same year as CND in Britain. At its first public meeting, in Dublin, a professor of physics at Trinity, the Nobel laureate Ernest Walton, called on the Irish government to continue to support all policies that might lead to nuclear disarmament. At the same event a prominent trade unionist, Donal Nevin, said that the Irish people could ‘feel proud’ of the stand taken on this question by Ireland’s representatives at the UN. The disarmament lobby asserted that CND demands in general were compatible with ‘Irish neutrality’ and Ireland’s initiative at the UN to prevent the proliferation of nuclear weapons.

Irish CND’s secretary, Betty de Courcy Ireland, urged women to become involved in political life and, in particular, to campaign against possible nuclear destruction. She had a basic Christian message for the Irish public: ‘All life is sacred, and any destruction of life is evil’. Ending the arms race, Chenevix argued, was the sane course of action.

The question of Ireland joining the EEC, and maybe NATO, fired up the nuclear disarmament campaign in 1962. Up to this moment there had been even fewer courageous men and women prepared to highlight the dangers of nuclear weapons, and, because ‘peace’ was seen as a Moscow-orientated cause, they were watched closely by the authorities. Some were communists and some, as in 1962, were not. Twelve years previously, G2, the Irish military intelligence directorate, identified the dozen individuals most involved in the ‘peace’ campaign, including a Church of Ireland clergyman. The following year, the secretary of the Department of External Affairs requested details from G2 on the leading light in the Irish Peace Campaign. G2 stated that this Trinity graduate’s communist involvement had cost him jobs in England, at the Royal Naval College—hardly a surprise—and in Ireland, with the Electricity Supply Board. Both the American and British embassies obtained details from External Affairs on Irish involvement in the international disarmament movement, which they saw as an instrument of Soviet propaganda. In the 1950s, however, with the Cold War in its most hysterical phase, even the Americans were not worried about Ireland’s anti-nuclear lobby. To illustrate the point, the US embassy informed Washington that two women seeking signatures for a ‘peace’ petition had been attacked by a mob in a Dublin suburb.

DETERRENCE AND DÉTENTE

Neither Kennedy nor Khrushchev were prepared to do the unthinkable and wage nuclear war in 1962. The following year the so-called Hot Line came into operation, staffed around the clock by technicians and translators, to prevent the misunderstandings that had occurred during the Cuban Missile Crisis. The nuclear age, and the Cold War, had entered a new phase of deterrence, and, later, détente. In addition, in January 1963 Ireland’s application to join the EEC fell along with Britain’s. The debate in Ireland about NATO membership, and consequent association with nuclear powers, came to a close. It would take twenty years for Irish CND to experience a revival, when there were renewed fears of the superpowers using nuclear weapons in Europe. However, the superpower rivalry of the Cold War came to an end in 1989.

Sixty years on from the Cuban crisis, the arguments articulated then still stand: nuclear war is unwinnable, immoral and insane. But what if, for example, Russia launched a ‘limited’ nuclear strike in Ukraine or another neighbouring state? Threats along these lines have been hinted at by Vladimir Putin. How would the world respond? How could the world respond? As in October 1962, we are back to contemplating the unthinkable.

John Mulqueen is the author of ‘An alien ideology’: Cold War perceptions of the Irish republican left (Liverpool University Press, 2019), now available in paperback.

Further reading

N. Browne, Against the tide (Dublin, 1986).

B. Evans & S. Kelly (eds), Frank Aiken: nationalist and internationalist (Sallins, 2014).

J. Horgan, Noël Browne: passionate outsider (Dublin, 2000).