Kilmainham Gaol

By Donal Fallon

On a recent (and regular) walking tour of the Kilmainham and Inchicore area delivered by historian Fergus Whelan from nearby Richmond Barracks, he joked of how the restoration of Kilmainham Gaol had become a little bit like the GPO on Easter Week 1916. Everyone, allegedly, was in there. The hard graft of local volunteers, from carpenters to plumbers, was instrumental in saving a site that had become essentially a film location. Lorcan Leonard, a driving force in saving the prison, recalled in the 1950s that ‘the memories of what had happened there made the subject still too raw for some, and successive governments continued to allow it to decline into ruin’.

The fight to restore Kilmainham Gaol is one of many tales told within its museum. Journeying through it, we encounter curious historic relics like the registration plate of the cab belonging to James ‘Skin-the-Goat’ Fitzharris, a member of the Invincibles, recalled for the 1882 Phoenix Park assassinations. While the museum is familiar to many, it is the top floor that has played host in recent times to a number of intriguing exhibitions that greatly broaden the focus of the museum. Now there are two simultaneous exhibitions, so complementary in focus and approach as to feel singular.

‘Hearts ne’er waver’ is an exhibition exploring the experiences of women imprisoned during the Civil War in Kilmainham Gaol, in Mountjoy and in a prison camp established at the former North Dublin Union. Voices presents work by artist Margo McNulty, a series of paintings and prints intended not only to evoke the atmosphere of Kilmainham Gaol for the women detained there but also to shine a spotlight on their individual characters. These photo etchings, of items like candle-holders or religious embroideries, give insights into the prison experiences of familiar names like Sighle Humphreys and Grace Gifford Plunkett.

On stepping inside the shared exhibition space, the visitor is first drawn not to an artefact but to sound. In the distance we hear ‘Kevin Barry’, sung beautifully by Kaija Kennedy. Later we hear ‘O’Donnell Abú’. These songs were both connected to the digging of escape tunnels. We learn that the first song ‘conveyed the news that some stranger was approaching, when work inside would cease’, but ‘O’Donnell Abú’ instead ‘would set them working again and all went merrily as wedding bells’.

The exhibition draws on the firsthand testimonies of the women imprisoned, but where to find such things? The Bureau of Military History witness statements, a ground-breaking oral history collection which illuminates the 1913–21 period, generally does not include Civil War testimony (though thankfully some participants did insist on giving Civil War memories). Instead, the exhibition draws on testimonies contained within the archives of the Gaol itself, including correspondence in and out of the prison. There is also brilliant use of Margaret Buckley’s The jangle of the keys, a 1938 memoir which remained rare and elusive for many years (it has fortunately been reprinted in recent times by the Sinn Féin Bookshop).

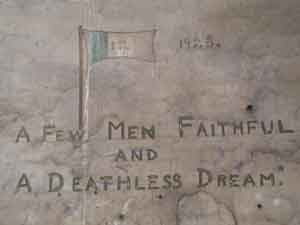

In telling the story of imprisonment at Kilmainham Gaol, the walls themselves speak. The exhibition makes good use of enlarged images of graffiti within the cells of republican women. One of the most familiar pieces of graffiti from the Gaol is present, with the words ‘A FEW MEN FAITHFUL AND A DEATHLESS DREAM’ from the cell of Brigid O’Mullane. Visible in the enlarged image, but something a visitor to the cell itself might miss, is the inclusion of the letters ‘I.R.’ within the tricolour. In August 1922, IRA leader Liam Lynch had instructed anti-Treaty forces to amend the tricolour to include the letters, ‘owing to the abuse of the Tricolour by the Free Staters during the present hostilities’. Another enlarged image shows us a fascinating message left behind by Sighle Humphreys, providing information on an escape tunnel: ‘Tunnel begun / in basement laundry / inside door on left / may be of use to successors / good luck / Sighle G’.

Political illustrations and cartoons were weapons utilised by both sides in the conflict. In the Freeman’s Journal there were the cartoons of Ernest Forbes, a.k.a. ‘Shemus’. These lampooned anti-Treaty leaders, showing de Valera as a mouthpiece for Erskine Childers (‘Now, don’t forget to say it exactly as I told you’). Women artists were central to the republican equivalent, and ‘Hearts ne’er waver’ presents examples of such work by Constance Markievicz and Grace Gifford Plunkett. That several of the women imprisoned here were artists makes the inclusion of Margo McNulty’s interpretive work, alongside the historical materials, particularly interesting. Such collaborations between historic museums and contemporary artists remain rare in mixed settings.

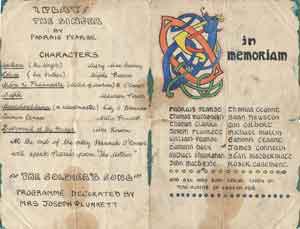

The artist Grace Gifford Plunkett brings visitors to Kilmainham Gaol today, her name synonymous with the 1985 ballad penned by Frank and Seán O’Meara and recorded in recent times by Rod Stewart. The ballad is heard from the terraces of Celtic Park, and long before the O’Meara song it was one of the great human stories of the Easter Rising, told in RTÉ’s 1966 Insurrection. Tours of the prison incorporate the chapel where she married Joseph Mary Plunkett on the eve of his execution. Here, we get insights into the mind of a different Grace, who was now herself a prisoner. A programme for a commemoration of the 1916 Rising, held in the prison on 24 April 1923, was illustrated by her and includes other names connected to the story of the Rising. Nora Connolly O’Brien, daughter of the executed James Connolly, is listed as reading the 1916 Proclamation.

Commemoration has long been integral to republican identity. Dorothy MacArdle noted her own belief that ‘it was good to be prisoners where the men of 1916 were prisoners, and to know that it was because we had been faithful to their deed and would not waste their sacrifice that we were here’. These women felt that they were keeping faith with the dead of Easter Week, but a tricolour created in the prison by Carlow members of Cumann na mBan reminds us how they themselves became part of the same narrative. The flag, showing the emblem of Cumann na mBan upon a tricolour, was last utilised at a republican funeral in Carlow in 1975.

In recent years Kilmainham Gaol has become a ‘must visit’ for many international visitors to Dublin. This appeal has led to overwhelmingly sold-out tours. Yet the Kilmainham Gaol Museum remains free to visit, separate from the tours of the Gaol, and the frequently changing exhibitions on its top floor should encourage us to revisit a place that we can now also leave at our leisure.

Donal Fallon is the presenter of the Three Castles Burning podcast and author of Three castles burning: a history of Dublin in twelve streets (New Island, 2022).