On the omission of Collins from Yeats’s poetic pantheon

By Fionnbharr Rodger

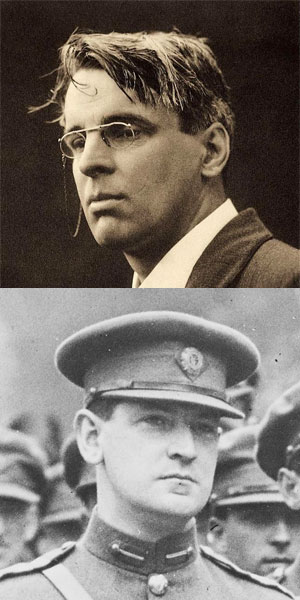

‘When news came in of the death of Michael Collins, one of the ministers recited to the cabinet … the entire Adonais of Shelley’, wrote Yeats in a letter to Olivia Shakespear. What is remarkable about this line is that it is the only explicit reference to Collins in all of Yeats’s writing, an output famous for invoking political and public figures such as Pearse, Connolly, Parnell, the ghost of Roger Casement and ‘MacDonagh’s bony thumb’. It seems strange that Michael Collins would not join this cast of characters, for, with the benefit of hindsight, his legend encapsulates the revolutionary period. At the time of the Truce and Treaty he became a romantic figure and a celebrity, with much gossip regarding his personal life, including a rumour propagated by Constance Markiewicz during the Treaty debate that Collins was secretly engaged to a minor member of the British royal family. There is something about his character that has made him an attractive topic for writers generally, such as Frank O’Connor, Brendan Behan, Louis MacNeice and Seamus Heaney. There is reason to suggest that this was a conscious omission on Yeats’s part, symptomatic of his wider tendency towards revision of his own life and narrative.

ONE FACE-TO-FACE MEETING

On at least one occasion the two men met face to face: at the house of Oliver St John Gogarty, the drawing room of which was described by Kevin O’Shiel, Orangeman, Irish Volunteer and election agent to Arthur Griffith, for the Bureau of Military History (WS1770). Gogarty’s house was frequently used to hold court by the leading lights of the Gaelic Revival and Sinn Féin movement. O’Shiel describes one occasion when it seems that Yeats and Collins were both in attendance, yet if they interacted with each other it appears to have been unremarkable enough not to have been recorded. O’Shiel recalled:

‘Yeats would occasionally break into verse, quoting from his own work or that of some other poet in what I thought, a curious, monotonous and rather stilted sing-song, marking the metrical emphasis by the rise and fall of his hand. Gogarty told me that Yeats had convinced himself that that was the way that poetry should be recited.’

It is possible that Yeats’s recitation of his own work may have come at the behest of Collins, requesting his favourite pieces, yet it is also possible that Yeats may not have required much persuasion.

The highlight of the night, at least as far as O’Shiel was concerned, seems to have been an exchange between Collins and George ‘Æ’ Russell. Russell was affectionally nicknamed ‘Mahatma’ by his literary friends, in recognition of his seniority in terms of age and grandeur. Mahatma, in his ‘quiet, sonorous voice, rather light for so big and bulky a man’, was in ‘excellent form that evening … reclining in his armchair in his comfortable loose fitting suit of rough Irish tweed, he pontificated with great verve, realising that he had a most important and attentive listener in Collins’, and he took the opportunity for ‘propounding some of his more mystical theories—the tranquil might of moral and spirit power as against the angry forces of evil in the contemporary “cosmos”’.

‘Mick, with his head bent towards him, pulling out his famous note-book that he was never without, and his fountain-pen’, then asked, ‘“but what is the point, Mr Russell?”’, which appears to have left Russell nonplussed and caused embarrassment to fall ‘on the company at the enormity of putting such a query, of all queries, to the prophet’. It is well established that Collins enjoyed the company of older people, having been born when his father was already 74 years of age; he seems to have shown every respect and courtesy towards Russell, and their meeting seems to have been mutually amicable. We see something of Collins’s personality here, in his deference towards his elder, his interest in the discussion of ideas and his insistence that there should be some practical application at the end of the philosophising.

Given Collins’s magnitude in the Irish political scene of the period and Yeats’s prolific output as a political writer both keen to make the nation in his own image and to record the events of the day, it does seem very strange that the former was not cast in the latter’s work, and one must ask whether this was a conscious sin of omission. One imagines at the very least that Collins would, on the night in question, have been very interested in Yeats.

COLLINS A FAN OF YEATS

It’s fair to say that Collins was a fan of Yeats. Having been born in the same year that ‘The Lake Isle of Innisfree’ was published in the National Observer, he was very well aware of the poet’s work. ‘To the day of his death he remained an extraordinarily bookish man,’ wrote Frank O’Connor in his biography. O’Connor wrote that Collins admired ‘Shaw and Barrie, Wilde, Yeats, Colum, Synge; knew by heart vast tracts of The Ballad of Reading Gaol, “The Widow in the Bye Street”, Yeats’ poems, and The Playboy’.

There were many opportunities for the two men to be made personally aware of each other, via their mutual connections. Firstly, Arthur Griffith was a very familiar figure to the poet, the pair of them having campaigned together against the Boer War, though primarily through Griffith’s position as a newspaper editor. In The enigma of Arthur Griffith, Colum Kenny recounted a meeting when Yeats went to Griffith’s office to complain about a review the latter had published of a poetry collection compiled by a friend of Yeats, criticising it for omitting works by Wilde and Alice Milligan. ‘There was a wobbly chair against the wall and a witness later recalled that Yeats “sat on the chair while expostulating. I heard a commotion myself, and on looking in—Yeats was floundering on the floor, the seat having collapsed from under him, to Griffith’s intense amusement”.’

Despite a bitter falling out over the role that Irish theatre ought to play in the struggle for independence—Griffith thought that it should have been more proactive—Griffith, as president of the Dáil, nevertheless nominated Yeats for the Irish Race Congress held in Paris in January 1922. Yeats also posited that he would have been tempted to accept if offered a position as culture minister in Griffith’s government, which would have made him a cabinet colleague of Collins.

SEÁN MACBRIDE

Secondly, there is Seán MacBride, for whom Yeats was a family friend who would pass regularly through his home in Paris whenever he felt a marriage proposal coming on. In 1921 Collins assigned MacBride to act as his aide-de-camp for the Treaty negotiations. During their time in London, MacBride lived with Collins at 15 Cadogan Gardens, reportedly ‘amazed by the amount of drinking Collins did’, even ‘revolted’ by it, but not to the extent of not joining in.

Collins and MacBride were later cast on opposing sides of the Civil War, yet the latter stated that there was never any personal animosity between them. At their final meeting at the Gresham Hotel, MacBride seems to have bought Collins’s ‘stepping stone’ argument that the Treaty was mere ‘breathing space’, and that Collins would regroup and resume fighting for full independence.

‘The Municipal Gallery Revisited’ (1937) contains a potential reference to Collins. That poem invokes Arthur Griffith, Kevin O’Higgins and Hazel Lavery, three figures but a single degree of separation away; the poem also refers to ‘an ambush’, which could be taken as a reference to Béal na Bláth … or it could refer to any of the other ambushes of the period.

Yeats was adept, when it suited him, at capturing the political moment—the poem as reportage. This is shown in ‘Easter 1916’, the first few lines of which provide a good portrait of the average IRA Volunteer: ‘Coming with vivid faces / From counter or desk among grey / Eighteenth century houses’ creates a useful image of the young, lower middle-class generation that fought the revolutionary war.

DISILLUSIONMENT

Yet there was a turning-point in Yeats’s later years, when political disillusionment saw him adopt a bleaker outlook nationally and a more revisionist, detached view personally. ‘September 1913’, with the lines ‘Romantic Ireland’s dead and gone / It’s with O’Leary in the grave’, suggests a bizarre degree of romantic naïvety, that he would join the IRB in the age of Parnell and later balk when violent revolution became more than a poetic concept, though Kenny argues that Yeats’s IRB membership was important in seeing the poet appointed to the Seanad in 1922.

‘Griffith, Connolly, Collins, where have they brought us? / Ourselves alone! Let the round tower stand aloof / In a world of bursting mortar’, wrote Louis MacNeice in his great work Autumn Journal. On the surface this is a vaguely humorous pun but, as usual with MacNeice, the comedy is a vehicle for the idea. Here he has chosen three figures who did not survive the revolutionary period but who were most prepared to live beyond it, with ideas for governance—three figures least taken by the idea of dying gloriously for Ireland, albeit they were all prepared to do so. MacNeice seems to have lamented that war claimed the best of us; the ‘round tower’ is a direct challenge to Yeats, and possibly a reference to ‘Man and the Echo’, published while Autumn Journal was being written in 1938.

It seems that Yeats the senator was highly prone to using diplomatic rhetoric when discussing his earlier political life; ‘did that play of mine’ seems to gently tiptoe around feelings of guilt, addressing his own responsibilities without addressing them. It is well established that Yeats was very well aware of Collins, which makes his exclusion from the poet’s output a glaring omission. It has to be considered that this was a conscious effort on Yeats’s part, and symptomatic of a wider attempt at personal revisionism—that there was some mental block where Collins was concerned. It is also unusual that, for possibly the two most written-about Irishmen of the twentieth century, where their lives converged has escaped the notice of secondary source material, especially considering that they each, in contrast, create a good, and interesting, profile of their respective classes within the society of the Ireland of their day.

Fionnbharr Rodgers has written articles for Northern Slant and Slugger O’Toole; he has had poems published in A New Ulster, Blackbird and Blackbox Manifold.

Further reading

C. Kenny, The enigma of Arthur Griffith (Kildare, 2020).

P. Hart, Mick: the real Michael Collins (London, 2005).

F. O’Connor, The Big Fellow (Nashville, 1937).

C. Tóibín, Lady Gregory’s toothbrush (London, 2003).