By Colum Kenny

There is an ironic twist to the circumstances of the birth of Éamon de Valera, then named ‘George de Valero’, in a Protestant charitable institution. Given that he is the politician who dominated the evolution of the Irish nation state in the twentieth century—with its paraphernalia of Magdalene laundries, mother-and-baby homes and dubious birth records—he might have ensured a better environment for those like himself who longed for knowledge of their fathers and whose mothers found themselves at the mercy of others. Yet even one of his own sons, a leading gynaecologist, colluded in various unlawful Irish adoption schemes that involved putting pressure on single mothers to give up their babies. The absence or falsification of Irish records left many people ignorant of the fact of their adoption and unable to trace their family histories when they discovered the truth.

THREE VERIFIABLE BIRTH AND PARENTAGE RECORDS

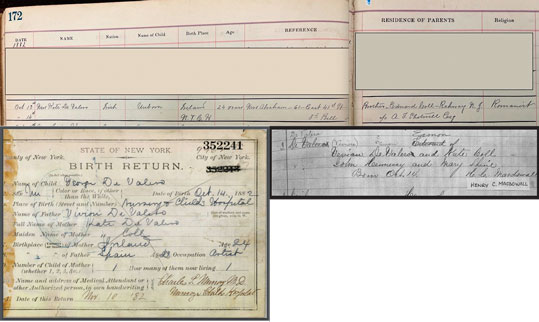

Before describing the grim nature of the Nursery and Child’s Hospital (NCH) where de Valera was born in Manhattan, it is worth laying out details of the only three contemporary records relating to his birth and parentage (and ignoring assertions or speculation).

According to the NCH Register 1878–83 (reproduced here for the first time), his mother, ‘Mrs Kate de Valero [sic]’, was admitted on 13 October 1882. Her religion was ‘Romanist’, her nation ‘Irish’ and her age ‘24 years’. The register did not require the name of her baby’s father. It did request ‘RESIDENCE OF PARENTS’. Kate’s parents were in Ireland, so she gave instead her fellow immigrant, ‘Brother, Edward Coll, Rahway N.J. c/o A.J. Shotmill Esq.’. She also gave a reference as required: ‘Mrs. Abraham, 61 East 41st St, 3rd bell’. No other detail was registered.

An official New York State Birth Return from the NCH, dated 10 November 1882 and signed by Dr Charles Murray MD of the NCH, returned ‘George de Valero’ as the only child of ‘Kate de Valero (maiden name Kate Coll), age 24, of Ireland’. It returned as his father ‘Vivion [sic] de Valero, birthplace Spain, age 28’, by occupation an ‘artist’. The form required neither the signature nor the home address of either parent. It is not known why Kate first called her child George. Her father was Patrick, while her uncle and brother, who both went to America, were Edward.

Thirty-four years later this original birth record was altered. On 30 June 1916 the New York Commissioner of Health approved a corrected record of birth, signed by de Valera’s mother (now ‘Catherine Wheelwright’ of Rochester, NY). Kate and her second son (Thomas Wheelwright) were that summer asking the US State Department to lobby the British, on the basis of de Valera’s US birth and citizenship, to reduce the prison sentence imposed on him for participating in the 1916 Easter Rising. This new certificate changed her first child’s name officially to ‘Edward de Valera’. As Kate then explained (according to a copy of an affidavit of 1916 in her name), she had ‘instructed Doctor Murray, the physician who attended during her illness, that the child was to be called “George” and in pursuance of such instruction the said Doctor Murray had the name recorded as such, but deponent [Kate] at the Baptism of the child gave it the name of “Edward”, by which name he has always been called …’ (UCD Archives P150/528). We do not know whether she meant that ‘the deponent’ alone later gave the child a different name rather than both of his parents agreeing to do so. The amended certificate of 1916 gives her own name in 1882 as ‘Kate or Catherine de Valera’. It also adds an 1882 address for herself and ‘Vivion de Valera [sic]’—61 East 41st Street, which, according to the 1882 NCH register, was also the street address of that Mrs Abraham who had provided Kate with a reference as required before her admission there. In 1916 Éamon de Valera’s father’s birthplace was given again as Spain.

The third contemporary record shows that Kate’s son was not christened until almost two months after his birth, on 3 December 1882—according to the baptismal register of the Church of St Agnes, Manhattan. A reason for this delay is suggested below. The register gave the boy now as Edward de Valeros [sic], his father as Vevian [sic] de Valeros [sic] and his mother as Kate Coll (not Kate de Valeros/Valera). It gave no address or other personal details. John Hennessy and Mary Shine are recorded as witnesses. The entry was later defaced by someone writing on it ‘Valera’ and ‘Eamon [no fada]’ and crossing out the letter ‘s’ in de Valera’s father’s registered family name ‘Valeros’. De Valera, as a child in Limerick and later at Blackrock College in Dublin, was known as Eddie. By 1916 he had adopted an Irish form of that name, Éamon.

These are the sole officially verifiable facts relating to Éamon de Valera’s birth and paternity. The de Valera papers in UCD include two photographs said to be of his father, one that he framed and kept on his desk when taoiseach and president and the other a miniature in a pendant (P150/167–9). Those papers also include statements by him and his mother and others about his father and his father’s family that are unverifiable, but his mother gave inconsistent accounts. As Mary Bromage wrote in her biography of 1956, ‘Those who heard about Vivion through Kate were to recall him variously as a sculptor, a professor, an actor, a linguist, a doctor, a singer, a raconteur …’. The recurrent US census and church and other records have not yielded to any researcher any evidence of a Vivion/Vivian/Vevian de Valero/Valeros who could be the father of Éamon de Valera, or of any such person’s birth, marriage or death before 1888. The name de Valero/de Valerio is rarely found in the US census then, although some variants turn up—mainly in US states adjoining Mexico. In 1880 a Cuban waiter, James Davalero [sic], lived with his Irish wife Julie in New York City. The name de Valera is even rarer in US records. In 1891 a Joseph de Valera, son of August, is found marrying a German woman and having children in New Jersey. And a Juan de Valera of Spain, aged 59, immigrated at New York in 1884.

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATE?

Kate Coll said that she married de Valera’s father in St Patrick’s Church, New Jersey. In the 1950s, however, Monsignor J.A. Hamilton of St Patrick’s Church, New Jersey, made ‘extensive searches’ of both Jersey City and New York church records for any marriage certificate of de Valera’s parents and found none (UCD P150/187).

De Valera himself and others too have tried in vain to find any further record of his father or paternal grandfather. His mother later said that his father left her in 1884 to go west for health reasons and died soon afterwards. There is no known official documentation that supports either this or what de Valera’s authorised biographers (T.P. O’Neill and Frank Pakenham) wrote in 1970, which was that his father’s name was Vivion Juan de Valera and his grandfather’s Juan de Valera. The first chapter of their biography seems to be based largely on what de Valera himself told them. When in Dartmoor Prison in 1916, de Valera sent his mother a note asking ‘to know more about grandfather’s family and business’. An earlier letter from his mother, referring to his father and grandfather, reached the UCD archives missing four pages for some unknown reason. As de Valera’s papers in UCD amply attest, the resources of both church and state were utilised in the search for his paternal details (UCD P150/171–2, 216–29, 1200, 3673).

In April 1885 Kate sent her first son back to Ireland with her brother Ned, six months after Eddie’s second birthday. Eddie de Valera as a child lived thereafter with relatives in rural Limerick.

Only one wedding certificate for Kate has ever been found, that for her later Catholic wedding on 7 May 1888 (at the Church of St Francis Xavier in Manhattan) to Charles Wheelwright. He was an English Protestant immigrant who came to the USA and found work as a coachman. Remarkably, as it happened, Charles seems to have worked earlier in London for a coachman named Edward Devall.

Having married Wheelwright in 1888, Kate in 1889 had a daughter, Annie, and in 1890 a son, Thomas (these were also the first names of Wheelwright’s English parents, Kate’s being Elizabeth and Patrick). She moved with her new family, upstate to Rochester. She rejected her first son’s pleas to bring him back to America. In US censuses (1900, 1910) she is recorded as the mother of just two children living or dead, not three. Kate and Eddie did exchange correspondence, with the future Irish president writing to her in his twenties: ‘Mother you will think it strange but many times I hear others talking of their mother I feel more or less an orphan. Fate has been rather hard on us’ (UCD P150/170).

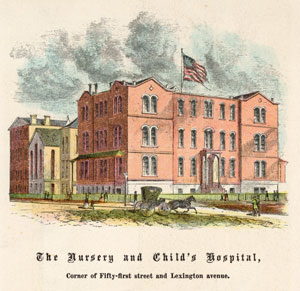

MANHATTAN’S NURSERY AND CHILD’S HOSPITAL (NCH)

Dev’s birthplace was fraught. Originally known as the Nursery for the Children of the Poor Women, the NCH stood where 51st Street meets Lexington Avenue. Founded in 1854, the Protestant institution took in children who were abandoned or badly mistreated and also poor pregnant women—with a preference in the first instance for married women. It is said to have been the first hospital in the USA to treat children under the age of twelve. Its secretary wrote in her report for 1881 that it ‘stands unique in itself, as it cares for children of such a tender age, and for mothers, in most cases, so young and so unhappy’. She added: ‘The cases are many and sad that are presented to the ladies on duty … and too many are the times where admission has to be refused for want of a room’.

There were no distinctly Irish names among the NCH’s many officers and managers, but settled New York families, including the Vanderbilts, were well represented. On its advisory committee was Erasmus Brooks, editor and politician, who was no friend of the Irish or of Catholics. He backed the ‘Know-Nothing’ movement, hostile to immigrants from Ireland. One Catholic critic had called the NCH a ‘proselytising nursery trap’. The hospital’s founding directress, Mary Du Bois, a friend of Brooks, was still working there in 1882. An Evangelical religious reformer, she worried about poor working girls tempted by the flattery of ‘fast’ young men. She explained to people how ‘an idle word and a slight pleasantry at first amuses, then is expected, and the result of flattered vanity is ruin. They are turned out, disgraced, and driven by the horrors of remorse often to suicide.’ The hospital in 1882 cared for 483 adults and 653 children. The death rate among immigrant mothers and their impoverished children in Manhattan was alarming. Irish women formed the greatest band of such mothers. One million or more young Irish women had poured into Manhattan in the previous few decades.

If a pregnant woman could afford to pay $25 for her board at the NCH, she could leave as soon after the birth of her own child as the physician deemed prudent. If, however, she was unable to pay, she had to give her service for three months, nursing and feeding both her own and another infant unless medically unfit to do so (two others if her own baby died). This condition may help to explain why de Valera was not baptised in a church for seven weeks after his birth. Provided that the conduct of any woman admitted was good during her stay at the hospital, the ladies of the institution might assist her to find work afterwards in ‘a desirable situation as wet-nurse or otherwise’. This condition may be the key to explaining why one American obituary for Kate de Valera would later state that she ‘entered a training school for nurses in NYC’. Éamon de Valera wrote that she worked as a nurse for a doctor in Manhattan at one point. In the 1910 US census she is described as a ‘nurse’.

Of 275 children admitted to the NCH in the year of de Valera’s birth there, almost a quarter died. Of another 219 actually delivered there that year, sixteen were stillborn and 43 died. Eleven women had also died in childbirth. One recurrent problem at the NCH was neonatal ophthalmia, which can have severe effects and even cause blindness.

‘LAWFUL WIFE’?

St Agnes’s Church in Manhattan came to use a standard printed certificate on which to give people details of their baptism there if later requested. It included after their father’s name the printed words ‘his lawful wife’ before their mother’s name. One such certificate, dated 1897, is among de Valera’s personal papers in UCD (P150/3). He seems to have taken consolation in it when rumours that he was ‘illegitimate’ circulated in June 1917. He was standing for election to parliament and reportedly wrote to his wife, ‘By the way isn’t “lawful wife” in Baptism certificate. I think it is—that would be sufficient to prove the lie …’ (‘Author’s copy’, T.P. Coogan, De Valera, p. 5). However, only the parents’ names ‘Vevian De Valeros’ and ‘Kate Coll’—and no such indication of Kate’s marital status—appear in the original handwritten register entry. The Church of St Agnes later adopted a more exact form of certificate, dropping the words ‘lawful wife’—as seen on copies of his baptismal details made in 1927, 1931, 1956 and 1961 that are also among the de Valera papers in UCD.

THE STIGMA OF ILLEGITIMACY

The status of illegitimacy was abolished in Irish law only in the 1980s. For much of the twentieth century it was both a legal and a social stigma. De Valera’s eagerness to confirm his parents’ marriage and father’s details may be viewed in that context. The way in which his own papers indicate that the possibility of his becoming a priest was deflected when he expressed it may indicate doubts about the status of his mother’s relationship with his father in the light of a missing marriage certificate, for in canon law illegitimacy was an impediment to ordination. His personal history resulted in rumours being circulated about him at election time, and even in the anti-semitic suggestion by John Devoy in New York that de Valera was a ‘half-breed Jew’ (UCD Archives, P104/259 (1–9)). Later, de Valera as taoiseach and president of Ireland was well positioned to mitigate the stigma of illegitimacy had he chosen to do so.

De Valera’s personal history mattered greatly to him, perhaps even as much as it has to many in the last and present centuries who have asked questions about their own origins or about their background in Irish mother-and-child homes—or about irregular adoptions that the State tolerated and that have left them lost for answers. We can only regret that Éamon de Valera did not do more when he was in a position to protect those who, like himself and his mother, found themselves dependent on strangers.

Colum Kenny is Emeritus Professor of Communications at Dublin City University and author of A bitter winter: the Irish Civil War 1922–23 (Eastwood Books, 2022).

Further reading

J. Miller, ‘Transatlantic anxieties: New York’s nineteenth-century foundling asylums and the London Foundling Hospital’, Annales de Démographie Historique 2 (2007), 37–58.

P. Murray, ‘Obsessive historian: Eamon de Valera and the policing of his reputation’, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 101 (2001), 37–65.

Nursery and Child’s Hospital, Manhattan, Annual Reports.