TG4, 24 May 2023

By Sylvie Kleinman

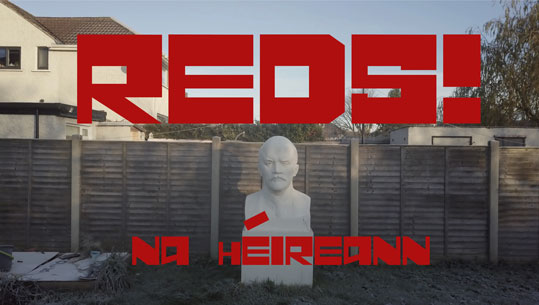

TG4 continues to air eclectic but probing documentaries. Conventional in format, this one is anything but boring and looks at the extremely off-centre topic of Irish adherents of communism. Given that Ireland was, as stated by a former member of the Connolly Youth Movement (CYM), Fergus Whelan, ‘the most conservative country in Europe’, this most secularising, supposedly levelling and culturally imported of left-wing movements never stood a chance here. Imagery, pace and soundtrack are all upbeat and entertaining. Although the documentary is probably aimed mostly at the uninitiated, many will enjoy its nostalgic throwback to 1970s smoke-filled meetings and sideburns and grainy TV clips, as well as the congenial and convincing frankness of the interviewees. It opens with a drone flying vigorously over an ordinary Irish residential neighbourhood, then descending into an ordinary back garden. Impervious to prevailing community values, the residents have elevated their humble family space with a large, crisp and lily-white bust of Lenin, gazing out assuredly at posterity. What tugged most at buried but vivid memories was the soundtrack, a few seconds of the melodious tones of a Red Army choir nobly ascending as we swooped down on Vladimir.

Reds! na hÉireann is not steeped in highbrow, academic analysis. Its effectiveness rests on its compelling human touch, letting the comrades construct the story outwards by reminiscing on the appeal to workers or students of a class-struggle ideology. Committed to recalibrating the social and economic order, they did not aim to make Ireland soviet. The narrative claims to tell the story from the founding of a party in 1921 until the fall of the Soviet Union, but it is tightly focused on the late 1960s to the 1980s, seemingly the peak of activism here. Evidently, once Lenin was unshackled from Stalin new beginnings were possible. The time-line is determined mostly by the direct evidence of the individuals. This makes sense, as who else could explain what an Irish communist thought and felt? At the outset we hear that in 1916 James Connolly and the Irish Citizen Army ‘helped show the way to Lenin, Trotsky and the Bolsheviks’ in the streets of Dublin. Not only are the latter conspicuously absent in participant reminiscences of the Rising but we heard this after seeing palaces stormed in the 1917 October Revolution. Roddy Ó Conghaile (like all interviewees, his identification is not translated in the English subtitles, in his case as his father’s son) related that in Moscow Lenin had told him that ‘Connolly’ stood head and shoulders above his social-democratic contemporaries in Europe. Connolly’s inspirational legacy is certainly indisputable, and his vision of an Irish workers’ republic motivated the next generations in Ireland. Fast forward to Whelan, aged thirteen in 1968, who ‘really liked’ the CYM marching in Che-style combat jackets at Bodenstown. But this was contested terrain: hissed and spat at by older members of Cumann na mBan, he was now a communist bastard who should go ‘back to Moscow’. Undeterred from attending his first meeting, he found himself amongst working-class people like himself, mostly printers and ‘very intelligent’. The dynamic of Irish communism, ‘passive’ by militant revolutionist standards, lay in the written word and disseminating the teachings of Marx, Engels and Lenin. This optimism was tempered with risks, hearing that ‘click’ when you started a phone conversation, and constant Special Branch and Garda surveillance.

Good-humoured, the youngest Red, the award-winning poet Belfast-born Sinéad Morrissey, reminisced about her communist upbringing, endless speeches and the ubiquitous plumes of smoke. Beckoning to ‘left-wing progressive people’ and being non-sectarian, in the North it attracted members across the divide. Helena Sheehan was most eloquent and not alone in having come to communism from the republican movement, around the time of the splits and brutal murders arising from the leftward shift of some republicans. From the 1930s to 1970 (the year of the merger with their Northern Irish comrades) Irish communists were ‘afraid’ to call their party by that name. Reds! is essentially a story from below rather than a scholarly analytical history from above. When telling of the Cold War and emerging ‘revolutionary left-wing groups’ in ‘Algeria and Cuba’, France and Italy are oddly mentioned last (and Germany not at all). In these more politicised and established labour cultures, even in rural areas, ‘workers’ and social movements trace their roots back to the 1830s and shaped national histories. For many French working-class families (like this reviewer’s maternal cousins), communism was the norm and very integrated into social activism, even national culture and rituals. Reds! is absorbing but a little narrow: we need to look elsewhere for those crucial missing years of the early and mid-twentieth century, e.g. the context in which Roddy Ó Conghaile met Lenin, and the obvious impact of international upheavals on activism here. Nor do we hear of the broad range of campaigns that Irish communists supported in the past five or six decades. Of Eoin Ó Murchú’s many revealing insights, his quick allusion to the Catholic Church here aligning communists with the devil is unsurprising, yet elsewhere accommodations were reached to overcome this apparent incompatibility.

The last third opens with a youthful Charlie Bird reporting in February 1990 on the opening of McDonald’s in Moscow, as people still queued for daily provisions—a blunt capitalist beginning of the end of a utopian vision. For some, the collapse of idealism had started with the 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, which ‘poisoned everything’. Having been convinced that they were on the ‘right side of history’, doubts increasingly crept in. Though people continued to travel to the Soviet Union and its satellite states, the corrupting influence of the heady welcome received in Moscow was incompatible with the grievances of Soviet citizens themselves. A ‘better form of socialism’ looked possible, but the opposite happened. Losing a ‘glorious idea’ or a misplaced (and dogged) belief can in itself be devastating, yet Sheehan still feels called to defend communism and Seán Edwards holds firmly onto his red flag. If, from a broader perspective, Reds! is not entirely satisfying, it started a popularised conversation about an unavoidable chapter of Irish political ideology.

Sylvie Kleinman is Visiting Research Fellow at the Department of History, Trinity College, Dublin.