By Clare O’Halloran

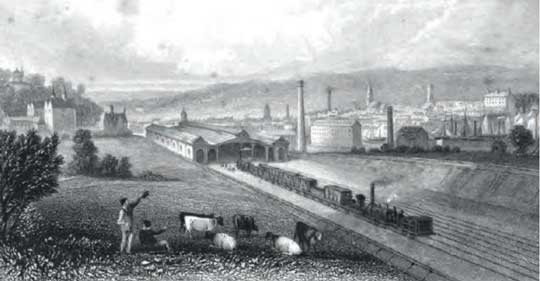

‘The stupendous power of steam has, within a very few years, annihilated all previous calculations of time and space.’ The sentiment of this breathless opening line of an all-but-forgotten 1844 history of Drogheda by the barrister and historian John D’Alton was a commonplace of the early age of steam transportation and especially the railway. The greatly increased speed of trains as a form of transport (20–30mph in the 1840s, compared to 8–10mph for the stagecoach) seemed to have caused space to shrink and geography to have been radically reconfigured. Even this history of a small Irish town 50km north of Dublin and a minor port and commercial hub for the north-east bore the marks of this steam-age revolution in the time–space continuum.

SPONSORED BY THE DUBLIN AND DROGHEDA RAILWAY COMPANY

Commissioned by the Corporation of Drogheda to write and publish a history of the town and its environs for a fee of £200, D’Alton required additional funding to include illustrations and therefore approached the directors of the newly established Dublin and Drogheda Railway Company for sponsorship. In return for a set of engraved plates, D’Alton agreed to include a separate account of their newly completed line and the landscape through which it passed. In fact, the work opens with this description of the railway, and thus not only highlights one historian’s view of the impact of rail travel and the developing railway infrastructure on the material remains of the past but also shows how a railway journey could provide a panorama of Irish history through the carriage window (so much larger and clearer than that of a stagecoach), and how the new velocity could meld ancient and modern into one apparently seamless whole.

D’Alton’s station-by-station rail travelogue is, on one level, focused on the excitement of the changing landscape panorama that a journey at speed can achieve. For example, he describes the line emerging from ‘the depths’ of a hill and ‘burst[ing] into scenes’ of rich and cultivated fields. More to the overall purpose of the book, however, the rail journey gave the illusion of closely connecting not only different times, ancient and more recent, but also uniting them with the present and future in the form of the newest technology and infrastructure. Thus, for example, D’Alton points out that the railway line is framed by two battle sites of great historic resonance, beginning with the ancient and moving forward, in space as well as time, to the modern. Close by the newly built Dublin station is Clontarf, where in 1014 the high king Brian Boru and his armies defeated the Vikings of Dublin and their allies, while from the terminus in Drogheda ‘almost in view’ is the battlefield of the Boyne, where the deposed James II was defeated by his son-in-law William in 1690, bringing about the end of the Stuart monarchy and transforming the future of Ireland. Reaching for similes that will convey the status of these sites, D’Alton dubs Clontarf ‘the Marathon of Irish History’, recalling the Greek defeat of the Persians in the fifth century BC, and the Boyne ‘the Waterloo of Ireland’, when Ireland was ‘relieved from devoted vassalage to a feeble, infatuated, and ungrateful dynasty’. But D’Alton is also alive to the need to convey to his tourist viewer that Ireland is not a country with its head turned solely towards the past. As the train leaves Dublin, he points to signs of modern industry visible from the new line: ‘Mr Kane’s oil of vitriol and bleaching powder works … a bottle factory [and] a soap boilery’.

FROM 1014 TO 1690

The main message conveyed in the memoir, however, is that in a journey time of about two hours—estimating a locomotion speed of 20mph and allowing for stops at the intervening stations—it was possible to travel from 1014 to 1690, and also, along intervening points on the railway line, to range swiftly back and forth between the ancient and the more recent past, eschewing the linear narrative of conventional history used in the history of Drogheda that follows. Instead, these random juxtapositions of new and old are solely shaped by what was visible from the compartment window, and, somewhat like an infinite Möbius strip, that haphazard pattern could be reversed by making the return journey south.

These intervening sites and views that D’Alton highlights are presented from two familiar perspectives. The first is based on the most iconic aspect of Irish history and therefore of Irish identity since at least the seventeenth century—the Early Christian era, when Ireland was said to have been a haven of sanctity and learning, in contrast to the rest of Europe, including Britain, which, in the aftermath of the fall of the Roman Empire, was overrun by ‘barbarian hordes’. This ‘golden age’ myth was subscribed to by both Protestants and Catholics, each identifying their religion with early Christianity as introduced by St Patrick. Although most of the most noteworthy monastic sites in the area (such as Monasterboice) were not on the route of the railway, there were some ‘golden age’ remains properly adjacent to the line, such as in the village of Lusk, where the tourist could enjoy through the carriage window the spectacle of the ‘singularly beautiful remains of a church and round tower … built on the site of an ancient abbey, founded … at the close of the fifth century’. He also singles out the ‘ruined church of Killester’ and the even more romantic remains of the church at Killbarrack, founded, he says, by a Welsh saint, said to have first introduced bees to Ireland.

THE PALE

The second prism used by D’Alton in his travelogue was strongly linked to the colonial history of Ireland. The Dublin to Drogheda railway line was located in the Pale, the area of most continuous English settlement, where the policy of Anglicisation was regarded as having had the greatest success, at least relative to parts further west. In line with travel literature extending back into the previous century, D’Alton highlights the areas where this colonial project seems particularly to have borne fruit. Thus the ‘English’ scene that confronts the traveller when the train emerges from a particularly deep cutting at Skerries is attributed to ‘a resident proprietary’ of descendants of the first English colonists.

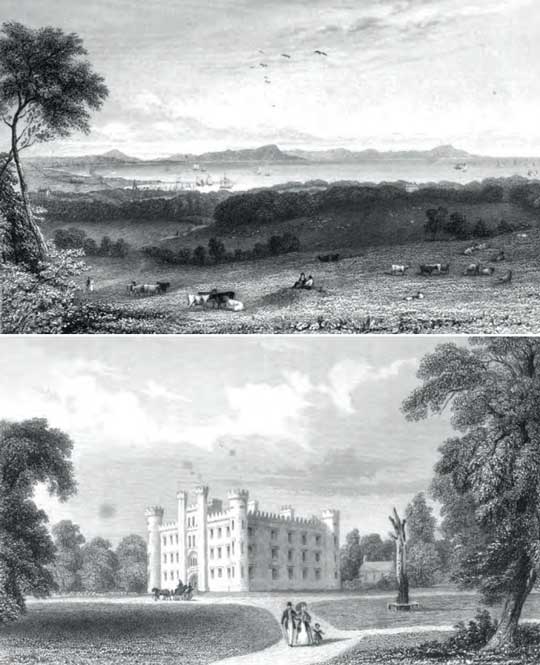

As the line proceeds northwards away from Dublin, this journey through the Pale becomes increasingly focused on these landowners and their efforts to effect improvements to their respective locales, which of course included allowing the railway to traverse their land. For example, Hampton Hall, an estate close to the village of Balbriggan belonging to George Alexander Hamilton, MP for Dublin and a director of the railway company, was described as presenting a ‘picturesque’ view from the train of a ‘noble house[,] pleasure grounds[,] beautiful undulations of the park [and] vistas through luxuriant and tastefully grouped woods’. The accompanying plate, however, is not taken from the railway line but from further west so as to include some of ‘the improving town of Balbriggan’, where three generations of the Hamilton family had invested heavily, building ‘several cotton works and a stocking manufactory’, a pier and ‘an inner dock’, making this a ‘place of some commercial importance’.

Above(Down): Gormanston Castle, seat of the Prestons, who found themselves on the losing side twice in the seventeenth century.

NO CONTINUITY IN FACT

The desired impression is of continuity and commitment on the part of landowning families in this long-settled and fertile part of the country, but it is undermined when it emerges that the Hamiltons, originally from County Down (and, to judge by their name, Scottish settlers of the Ulster Plantation), had only acquired the estate in the eighteenth century. It had belonged to Richard Talbot, Lord Tyrconnell, lord deputy and James II’s right-hand man in Ireland, and was confiscated and disposed of following his attainder for treason. George Hamilton remained true to his Williamite ancestors by being a fervent supporter of the Protestant interest in Ireland, a steady opponent of Daniel O’Connell at Westminster and a founder of the Conservative Society of Ireland.

Thus the warfare and rebellions of the seventeenth century had left their mark on the original colonial families of the Pale and on their lands. Most prominent here were the Preston family, holders of the title Viscount Gormanston and, since the fourteenth century, owners of Gormanston Castle and estate, through which the railway ran. Repeatedly unwise in their political choices in the seventeenth century, the sixth and seventh viscounts found themselves on the losing side, the sixth in the Confederate War of the 1640s and the seventh in the Williamite war of 1689–91, and both were declared outlaws. As D’Alton explains, their descendants in the eighteenth century had to go through lengthy legal processes, taking the best part of 100 years, firstly to get some of their lands and then their title restored.

Reinforcing this competing sense of a far-from-settled land, the railway line in quitting Gormanston crossed via ‘a noble viaduct’ the ‘exceedingly picturesque’ Nanny River, over whose ‘wooded banks’ towers Ballygarth Castle. This had belonged to the prominent Old English Netterville family, D’Alton informs us, but after the defeat of the Old English and Gaelic Irish Confederate army in 1652 it formed part of the Cromwellian confiscations and passed to a New Model Army soldier, George Pepper, in whose family it remained.

MEGALITHIC PASSAGE GRAVE

This accelerated journey via the railway through the history of the Pale reveals the fractures in Irish history caused by lengthy phases of war, conquest, expropriation and colonial settlement. No amount of picturesque views of the fertile and prosperous landscape could entirely mask the trauma still associated with that legacy. But there is a further source of unease to be found in this travelogue, which is linked to the very technology that had made it possible to traverse the Pale at a speed unimaginable to those who first established it. On the Gormanston estate, D’Alton describes a ‘long secluded mount, whose sacred remains are immediately contiguous to the railway’. This was a megalithic passage grave, one of a number in the townland of Knocknagin, which archaeologists have since identified as an important Neolithic burial complex dating from around 3500 BC, suggesting that it is a predecessor of the somewhat later Boyne Valley cemeteries of Newgrange, Knowth and Dowth. With the permission of Viscount Gormanston, the ‘sacred remains’ beside the railway line had been excavated in 1840 by neighbouring landowner George Hamilton, who discovered therein ‘a chamber, constructed of huge flags, some of them more than six feet in height’. Hamilton, however, in a letter to D’Alton, quoted by the latter, reported that he feared that many of these flagstones had since been used in the construction of the very railway line that D’Alton is describing.

The idea of time’s ravages eventually obliterating the remains of the past was long familiar to antiquaries and historians, but what if, in creating a modern communications infrastructure, not only time but also its spoliations were accelerated, creating a greater and more obviously man-made disjuncture between past and present? We find further signs of the unease that this generated in D’Alton’s historical survey of the environs of Drogheda in volume two of the work, where, on the one hand, he referred to the Boyne Valley as ‘an undisturbed, unexplored theatre for antiquarian investigation’, while on the other admitting three pages later that the Neolithic mound at Newgrange ‘served as a stone quarry to the vicinity, and the surrounding roads were paved from this repository’. In the same year, 1844, Thomas Davis, writing in The Nation, raised the alarming prospect of a new road being driven through the mound itself by the owner of the land on which Newgrange stood. For Davis, the fate of this ‘temple’ was in the hands of the ‘Drogheda antiquarians’, by whom he meant ‘men of education, ability [and] taste … who respect grey antiquity, and would secure its heirlooms to their children’, and who therefore had to oppose ‘the Meath road-makers’.

One of the lessons to be learnt, however, from D’Alton’s account of the Dublin and Drogheda Railway is that, where rail projects were concerned, landowners straddled both sides of the divide—at once investors in the railways and sellers of the land on which the network would be built, and yet also stalwarts of the antiquarian learned societies set up to document and protect Irish heritage. George Hamilton, landowner, MP, chairman of the directors of the railway company and excavator of the Knocknagin passage grave, is the prime case here, writing a report on that excavation that was published in the Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy in 1845. Significantly, perhaps, he omitted in that report to say that the flagstones from the passage grave had been used in the building of the line. Then as now, in the conflict between the development of commercial infrastructure and preservation of the built heritage, the asymmetries of power always favoured those who could claim to be facing the future as well as honouring the past.

Clare O’Halloran lectured in history at University College Cork until 2021, when she retired.

Further reading

J. D’Alton, A history of Drogheda, with its environs; and an introductory memoir of the Dublin and Drogheda Railway (2 vols) (Dublin, 1844).

P.J. Geraghty, ‘The Dublin and Drogheda Railway: the first great Irish speculation’, Dublin Historical Record 66 (1–2) (2013), 83–132.

W. Schivelbusch, The railway journey (Berkeley, 2014).