By Madeline O’Neill

In 1900 in Pienaarspoort, some fifteen miles east of Pretoria in the South African Transvaal Republic, an Irish Catholic major in the Connaught Rangers, Maurice George Moore, considered the orders forbidding him to provide supplies for a group of Boer women and children who had been removed from their farms. Insufficiently supplied with food, they were left in a small church to starve. In that same year, Lt. Jourdain, a young Anglo-Irish officer under Moore’s command, described a ‘piteous’ scene at a spruit on the Caledon River, with ‘Boer women in open wagons, being drenched, with crying children all around them … one of the women was dying in one of the wagons but no notice was taken of her’. When he returned to the South African Union on a diplomatic mission for Dáil Éireann twenty years later, that same Catholic officer, now Colonel Maurice Moore, wrote to the South African premier, Jan Smuts, that he ‘had suffered in mind and conscience’ for the actions he was ordered to undertake against the Boer people during the second Anglo-Boer War, 1899–1902.

Moore’s reluctant complicity in the ‘scorched earth’ policy adopted by Kitchener, which enforced the removal of Boer women, children and the aged to concentration camps, caused him to draw parallels with the Cromwellian devastation and destruction of seventeenth-century Ireland. He witnessed an ‘English gentleman’ express satisfaction at burning 22 farms near Bronkhurst station, and observed that ‘two and a half centuries ago Cromwell might have said that he had punished the enemies of the Lord, but even he would have regarded it as an unfortunate necessity and would certainly not have gloated at the misery and wretchedness entailed by such acts’. Moore may have been forced to comply with Kitchener’s orders, but he found ways to subvert them and to prevent some of the farm removals. In so doing, he was to become an example of Alvin’s Jackson’s much-quoted description of the Irish in empire as both bulwark and a mine within its walls, as he practised subtle strategies of collaboration and resistance, often simultaneously. He earned, for example, both military honours for services to empire and the sobriquet of ‘Boer Colonel’ for his sympathetic treatment of the Boers.

COLONIAL DISCOURSE FUSED WITH NATIONALIST RHETORIC

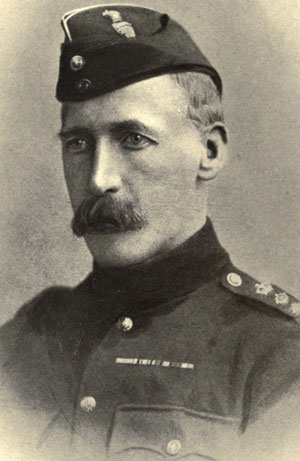

Major Maurice George Moore, as he was in 1899 when he went to war, was the younger son of Catholic landed gentry in Mayo. He was described as having an upright carriage and being typical of the Catholic families of Ireland. He possessed aquiline features and a military moustache and was regarded as kindly, genial and approachable. His more controversial brother was the novelist George Moore; his father, George Henry Moore, had been a founding member of the Independent Irish Party in 1852 and a supporter of the Tenant League. He also had a reputation as a landlord who came to the aid of his tenants during the Great Hunger. As the younger son of a family impoverished by the Famine, Maurice joined the Connaught Rangers in 1874. His background had given him a set of patriotic ideals founded on the earlier loyalism of a Catholic élite with Whig-liberal tendencies. These had mutated under the influence of his father’s more radical politics and the nineteenth-century nationalist cultural and literary movements into a more ardent, but not then separatist, nationalism. None of this was inconsistent with his sense of military loyalty or his identity as an officer in an Irish regiment in the British army. This confluence of nationalist identity and imperial service was expressed in Moore’s relationship with the soldiers under his command, which was both paternal and spiritual. He led ‘his boys’ in prayer every night on their sea voyage to South Africa, and in the dawn before battle he led them in the rosary and in an act of contrition. With Moore’s approval, the regiment frequently carried green banners and sang rebel songs as it marched to war against the rebellious Boers.

THE CAMPAIGN

Moore departed for Natal on the troop ship Bavarian on 28 November 1899 as one of three majors in the Connaught Rangers, with the command of B Company. At the age of 45, he had served empire in India and South Africa for more than twenty years. He was not an ideological tabula rasa when he first set foot on the African continent. His earlier impressions of South Africa from the Xhosa and Zulu wars of the 1870s were representative of contemporary colonial discourse fused with nationalist rhetoric. His accounts of the Zulu warriors contained many of the markers that distinguished colonial constructions of an African ‘other’, and his descriptions of the veldt exulted in the topography and the clear air. By the 1900s the British propaganda on the Boers that he had absorbed before his posting to South Africa was displaced by a more intimate understanding in which he came to regard the Boers as an exceptional people, although he continued to construct Boer culture within the familiar parameters of a British ruling élite.

Arriving in Durban on 1 December 1899, he joined Maj.-Gen. Fitzroy Hart’s Irish Brigade, which included the Inniskilling Fusiliers, the Dublin Fusiliers and the Border Regiment. In the first stages of the war, known as ‘Black Week’, the British suffered three humiliating defeats at the hands of the Boers, at Stormberg, Magersfontein and Colenso. Moore and the Rangers arrived in Durban in time to take part in the third of these major defeats at Colenso, where the Rangers were fired upon at the Tugela River by the Boers, who were armed with new Mausers. The Times recorded that the ‘Dublins and the Connaughts advanced magnificently against the almost overwhelming fire, men falling at every step’. But it was at Hart’s Hill on the final stage of Sir Redvers Buller’s offensive at the Tugela Heights that the ‘Boys from Roscommon and Mayo and other counties, Catholic and Nationalist’, were to ‘suffer so terribly’, as John Redmond protested in Westminster at the lack of mention of their sacrifice in the national press. A Mayo newspaper carried a report of ‘12 days desperate fighting’, in which the Dublin Fusiliers, Connaught Rangers and Inniskilling Fusiliers forming General Hart’s Irish Brigade were almost decimated.

By the second stage of the war, with the capture of Pretoria and Johannesburg in the Transvaal and Bloemfontein in the Orange Free State, Moore was placed in support of the flying columns of Generals French, Mahon and Hamilton as they swept the veldt from Kimberley to the Transvaal through Johannesburg, Heidelberg and Pretoria and then north-east to Balmoral. By December 1900 he was in Aliwal North in the north-east of the Cape Colony, attempting to prevent the still-active Boer commandos from entering the northern Cape Colony, where they might enlist the support of the Cape Afrikaners. By the third stage of the war, the veldt was dotted with garrisoned blockhouses to flush out the remaining Boers. Given the vast distances to be covered, Moore began a campaign to train the Rangers as mounted infantry, encountering resistance from his commanding officer, Gen. Hector MacDonald. He finally received permission from a reluctant Kitchener but little or no practical help, as the depot refused to supply the necessary mounts. Moore obtained horses from Aliwal, mostly runaways in poor condition, reconditioning them for use in the infantry and training the men both to ride and to care for their mounts. By June 1900, 440 men in five mounted companies were ready for operation in the Cape Colony and Orange River Colony and began an eighteen-month period in pursuit of the Boer commandos in the Aliwal Burgersdorp district.

Moore was ordered to Aliwal to intercept the notorious and elusive Boer general Fouché, who was an important symbol of resistance for the Boer nation. The guerilla-style skirmish that followed was reported as a victory of sorts for the British, while the Boers remained jubilant at Fouché’s continued freedom. Fouché had captured two of Moore’s men and threatened to execute them in retaliation for executed Cape rebels. Moore had treated Fouché’s captured field cornet, Olivier, with kindness before he died of his wounds, sending Fouché the message that ‘no burger had been hanged for fighting against the British’ and that he and the Connaught Rangers had treated his people with courtesy and consideration, and that he expected the same in return. Fouché released the two Rangers and thanked Moore for his care of Olivier. Moore emerged as something of a hero for his courageous, rational, dignified and honourable conduct, while Fouché continued to roam the veldt and three of the Rangers ended up in graves on the Zuurvlakte plain.

ALTERNATIVE NARRATIVE

When the alternative narrative of Moore’s involvement in the war is examined, it can be seen to differ markedly from the official one of service and devotion to duty. In this narrative Moore was more an agent of subversion than a participant in empire. While he was in the Aliwal/Burgersdorp district in the north-eastern Cape, he visited ‘nearly every farm in a very extensive district and made acquaintance with the owners’. He followed his orders in these farm visits and then subverted their execution by pretending not to understand when the questioned Boer women proudly declared that their menfolk were ‘on commando’. He entered into their records that they had died or were away, thus saving the women from imprisonment. Witnessing the lack of military opposition to Kitchener’s orders to shoot to kill the Boer leaders, Moore exposed Kitchener’s tactics in a letter to his novelist brother George, who had the letter printed in the Freeman’s Journal. It was copied in the London Times and the contents made their way to the Cape newspapers, causing an uproar.

Moore’s disaffection was not limited to the treatment of the Boer nation or the military tactics employed to capture the Boer leaders; it included concern at the treatment of his Irish troops. It was at the battle at Hart’s or Inniskilling Hill, which was part of Buller’s offensive at the Tugela Heights to relieve the besieged Ladysmith, that Moore’s dissent was most obvious. He expressed anger at Gen. Hart, the leader of the Irish Brigade, for the carelessness with which he sent the troops into battle. The heavy losses suffered by the Connaught Rangers and the Inniskilling Fusiliers moved Moore to make a blistering attack on the lack of credit given to the Irish regiments. ‘Had they been Highlanders or officers of the Staff, their pictures would have appeared in every illustrated paper.’ He wrote bitterly that ‘many a Victoria Cross had been granted for less merit’. It was reported in the Connaught Telegraph that a major in the Connaught Rangers from a prominent Mayo family had expressed opposition to the treatment of the Irish regiments in the war. This dissent was voiced in the House of Commons by Tim Healy, who called for the identity of this officer to be made clear, but once again Moore escaped detection.

His ethical engagement with the effects of military policy arose from his own moral vocabulary originating in his Irish Catholic élite background. His father’s humanitarian actions during the Irish Famine found a resonance in his son’s attempts to save the Boer women and children from the concentration camps. The fact that most of the Irish in the higher command of the British army were from Anglo-Irish Protestant backgrounds tends to obscure the presence of those who, like Moore, identified strongly as élite, Irish and Catholic. Unlike those Anglo-Irish officers described by Jane Ohlmeyer, who was writing of the Irish garrisoned in India, Moore did not view his ‘Irishness as something of a liability, even an embarrassment’, but rather as a crucial part of his identity—albeit it was an identity that he felt the army frequently preferred not to acknowledge. Moore retained the title of colonel to the end of his days, but his estrangement from British army authority and imperial rule deepened and became entrenched, so that by the 1920s he was firmly on the side of Irish separatism.

Moore’s return to South Africa to engage Premier Smuts’s support at the upcoming Imperial Conference in 1921 awakened former memories, which he was unafraid of referencing when he negotiated with politicians, many of whom had been commandos and members of a Boer landed class. He reminded his hosts that he had been responsible for the letter to the press revealing Kitchener’s orders to shoot to kill in 1901.

Moore had a reputation among his fellow officers for going his own way, embodying a singular character that often emerged in imperial accounts of travel, exploration and adventure, representing the values believed to be inherent in imperial expansion: autonomy, self-will and the ability not only to endure difficult circumstances but also to thrive on them. Imperial soldiering and Irish nationalism found a nexus in his person, creating an ambivalent set of loyalties that often defied simple identification.

Madeline O’Neill completed a biographical study of Senator Colonel Maurice Moore in 2018.

Further reading

A. Jackson, Ireland, the Union and the Empire, 1800–1960 (Oxford, 2005).

J. Ohlmeyer, ‘Ireland, India and the British Empire’, Studies in People’s History 2 (2) (2015), 169–88.