RTÉ1, 20 December 2023

Fís Éireann/Screen Ireland Blueprint Pictures

By Sylvie Kleinman

This disturbing documentary on a somewhat unusual atrocity of the early Troubles concludes with a deeply heartfelt expression of hope for the future. Engaging with events at a macro-historical level to locate them on a time-line, it mostly historicises the impact on survivors of a particular act of wanton brutality, triggering a chain of tragedies in one family for a quarter of a century. In the Senate chamber of the Northern Ireland Assembly on 11 March 2023, Tanya Williams-Powell spoke during the European Day of Remembrance for Victims of Terrorism. Opening up, she said, could help alleviate the grief and guilt that victims and families of violent ideologies carried: it was possible to break the cycle of intergenerational trauma.

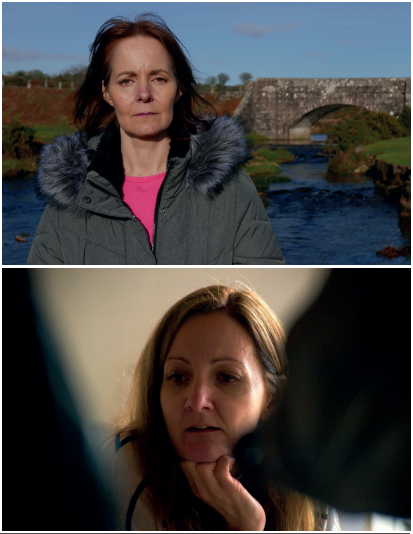

Half a century after the kidnapping and brutal killing of her maternal grandfather, Thomas Niedermayer, in Belfast on 27 December 1973, she had overcome depression and loved her life as the mother of two young daughters in rural England. This relatively brief yet highly effective film reconstructs very mediatised events from her personal perspective and that of her sister, Rachel Williams-Powell, who had escaped to Australia to ‘start anew’. The eventual discovery of Niedermayer’s remains in 1980 and revelations of what had actually happened to him had not brought the family closure. A decade later, his wife Ingeborg took her own life. Their youngest daughter, Renate, who had opened the door to the abductors, then starved herself to death, after which her older sister, Gabriele Williams-Powell, took her own life, as did her husband Robin in 1999. It was then that their two daughters, Tanya and Rachel, discovered press cuttings and began to reconstruct what they had never been told about.

Niedermayer came to Belfast with his family in 1961 to manage Grundig’s new electronics factory, the first established outside Germany. It manufactured their iconic tape recorders and successfully created much-needed employment across the sectarian divide. The workforce was apparently quite contented and respected their manager, whose local reputation was enhanced in 1971 when he became honorary consul for West Germany in Northern Ireland. By the summer of 1972, however, Northern Ireland was plunging into a terrible time ‘of slaughter, of mayhem, of butchery’, as journalist Kevin Myers recalled, then reporting to the sound of repeated bombs in Belfast. Yet Niedermayer stayed. A ‘good man’ who provided employment and now very much in the public gaze, he became ‘a soft target’, according to the plain-speaking former RUC Special Branch detective inspector William Matchett. At work, Niedermayer had already clashed with one shop steward, Brian Keenan, who left and became a hard-edged and brutally persuasive IRA commander. The background to the abduction was linked to the IRA 1973 car-bombing campaign in London. When Dolours and Marian Price were convicted and received life sentences, they went on hunger strike and were force-fed. Keenan became involved in a campaign to have them moved to Northern Ireland, and masterminded the abduction of someone prominent enough to blackmail the British government. But negotiations behind the scenes suddenly stopped. Ingeborg had long remained convinced that her husband was still alive. She and her daughters experienced the various forms of disinformation prevalent at this time, including gossip and innuendo about Thomas. Predictably, this related to his private life, or perhaps he was a secret arms trader. Myers bluntly reflected that he had been duped by fabrications and that the press, including himself, had behaved appallingly.

After Keenan’s arrest in 1979 and his sentencing, an informant revealed the truth to Alan Simpson, a former RUC detective superintendent tasked with re-opening the case. He supervised a dig in a rubbish dump and, merely one mile from the family home, Niedermayer’s body was found in March 1980. He had in fact died three days after the kidnapping, having been clubbed in the head with the butt of a handgun when he had tried to escape. This bungled operation had to be silenced, and the victim was buried face down in a shallow grave, gagged and his hands bound, though already dead. Former IRA Volunteer Shane Paul O’Doherty recalled how a buddy in September 1970 had ‘discovered the Provos’ and urged him to be sworn in. At fifteen, they were exhilarated to be ‘secret agents’ of the IRA at one minute, but at the next threatened by their new controllers. If they squealed, they’d be shot dead. Interviewees evoked this ruthlessness and total disregard for victims, and Keenan’s grandiose patriotic funeral was contrasted with the painful fate of the Niedermayers.

Familiar footage of bomb scenes alongside carefree children playing was here juxtaposed with a compelling international layer, strengthening the film’s historicising value. Ingeborg was from north Prussia in eastern Germany, and as a teenager had experienced vicious atrocities as the Russians moved west in 1945, losing several relatives. Some graphic footage left viewers in no doubt of the trauma she had carried with her into adulthood. That she was actually being treated in hospital for her mental health when Thomas was taken was not silenced, and after she had bravely pleaded with the abductors not to harm him personal issues became public. It was moving to see Tanya, now out of ‘the dark place’, enjoy watching an interview of her stoic mother Gabi, then aged only twenty. Renate as a child had loved rescuing animals, and was working in a South African shelter when she died. Projecting personal experiences outwards in a broader historical context, Face down is rooted in the present, though it does not engage with the legacies. Niedermayer’s granddaughters, of a generation accustomed to public and essential conversations about post-traumatic stress disorders and the tackling of depression, turned back to Belfast and reached out to others, and met their German family.

The script, by the former RTÉ producer David Blake Knox, based on his 2019 book of the same name, flows well and tightly. The documentary was released in cinemas last August and was widely commented on. Its television broadcast, just before Christmas, triggered some blunt and uncompromising reviews on how the context and perpetrators of this cruelty are viewed half a century later.

Sylvie Kleinman is Visiting Research Fellow at the Department of History, Trinity College, Dublin.