By Daragh Fitzgerald

The Coleraine Historical Society is celebrating its 40th anniversary this March, and to mark the occasion a ruby type is used on the front cover of the latest volume of their journal, The Bann Disc. This diverse collection of essays concerning all things Coleraine (and its environs) contains something of interest for all shades of history-lovers, from the story of ‘Wee Joe’ Scott, an eighteenth-century highwayman, to golfing sensation May Hezlet, who in 1899, aged seventeen, won the Ladies’ Open Championship and the Irish Ladies’ Open Championship, both on the links course at Newcastle, Co. Down.

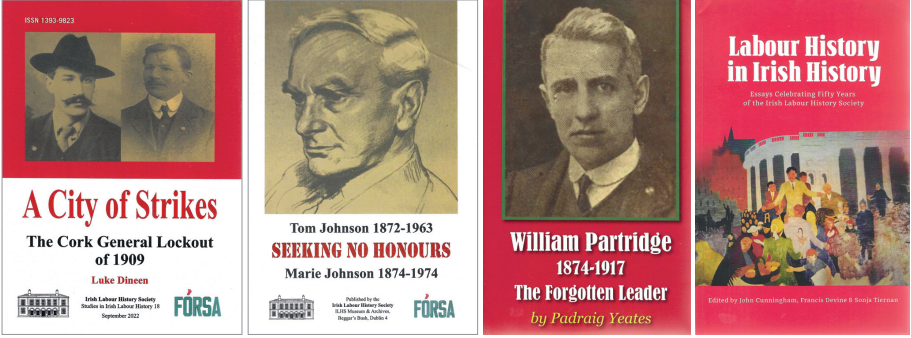

Another group—the Irish Labour History Society—marked its golden anniversary last year. It is both a cliché and a truism that labour history has been rather neglected in the mainstream historiography of Ireland, and in the popular consciousness the epic set piece of the 1913 Dublin Lockout tends to dominate, perhaps to the detriment of broader discussions regarding labour and class. The Irish Labour History Society has since its inception endeavoured to buck this trend and instead to augment and broaden our understanding of labour history, and Luke Dineen’s A city of strikes: the Cork General Lockout of 1909 is a fine manifestation of this enterprise. Remarkably, A city of strikes is the first publication dedicated solely to the lockout in Cork, even though the clash contemporaneously inspired plays by two of Cork’s most famed sons—Daniel Corkery and Terence MacSwiney. Cork, like every Irish city outside Ulster, deindustrialised across the nineteenth century in the wake of the Act of Union, producing entrenched poverty and a pool of unskilled labour in the city that would be the bread and butter of Larkin’s Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union. The Cork Lockout in many ways pre-empted the storied clash between labour and capital in Dublin four years later, as Cork’s version of William Martin Murphy, Sir Alfred Dobbins, formed an Employers’ Federation in the city to combat ‘Larkinism’ which bullishly prolonged the strike for as long as possible to bleed the Transport Union white. Sinn Féin’s newspaper took a rather dim view of Larkin as a meddling Englishman, while the workers formed a proto-Citizen Army to mount a defence against the regular attacks from strike-breakers and the RIC.

Despite leading the labour movement through the latter half of the revolutionary period and several general strikes, Tom Johnson is also a victim of the collective amnesia displayed towards labour history in Ireland, while Marie Johnson—Tom’s wife, a suffragette, trade unionist, socialist and peace activist in her own right—has been completely marginalised. Tom Johnson 1872–1963, Marie Johnson 1874–1974: seeking no honours provides biographies of both of their lives and includes Tom Johnson’s statement to the Bureau of Military History in full, documenting the extent of his and labour’s contribution to the revolutionary period, along with the Democratic Programme, which he drafted, and reflections on his legacy from the disparate perspectives of a contemporary, Cathal O’Shannon, and one of his successors, Brendan Howlin. Johnson had the unenviable task of leading the labour movement in the aftermath of Larkin’s departure to America and Connolly’s execution in Kilmainham, and he is excoriated by many who remember him today for wilting in those titans’ shadows. While much of the ink spilled over the last century regarding Johnson has been polemical, it is true that he was not a revolutionary but a social democrat—although of the old vintage, much closer to Marx than to Blair. The zenith of Johnson’s career was his leadership in the movement to defeat conscription in 1918. That year ended, however, with Labour’s decision not to stand in the general election, a decision for which Johnson has never been forgiven. He had an unfortunate tendency to fudge exigent issues like this, illustrated in his presidential speech to the Irish Trade Union and Labour Party Congress in 1916, when he conflated the execution of Connolly with the Allied war dead, which could have been lifted right out of the Decade of Centenaries ‘shared history’ playbook.

Padraig Yeates’s William Partridge 1874–1917: the forgotten leader documents the life of another neglected labour leader. Born in Sligo, William Partridge was active in labour politics in Dublin and played a key role in both the Lockout and the Easter Rising before his unglamorous death from nephritis in 1917. Partridge typified many of the intellectual currents of the ‘Vivid Faces’ generation: a committed nationalist and trade unionist who became a syndicalist under the influence of Larkin, he was equally a devout teetotalling Catholic guided by Rerum Novarum, and as such never embraced socialism. A fine public speaker, contributor to The Irish Worker and Labour councillor, Partridge claimed to have stopped the first tram at the start of the Dublin Lockout; he also recruited Michael Mallin to the Citizen Army and served under his command at Easter 1916, saving Margaret Skinnider’s life during the Rising. Fellow Sligonian Constance Markievicz gave the graveside oration at Partridge’s funeral, in which she credited the religious devotion he demonstrated during the Rising for her conversion to Catholicism.

Labour history in Irish history: essays celebrating fifty years of the Irish Labour History Society is a perceptive collection of writings covering topics as diverse as rural labour, nineteenth-century trade unions, Rosie Hackett, the Belfast relief riots of 1932 and Travellers’ rights activism, from a stellar panel of contributors that includes Terry Dunne, Emmet O’Connor, Mary McAuliffe, Fearghal MacBhloscaidh, Margaret Ward and Uachtarán na hÉireann Michael D. Higgins.

Central to the Transport Union and the Dublin Lockout were the dockworkers of the city’s port, and Dublin Port chief engineers covers the lives and careers of the two men primarily responsible for its construction, Bindon Blood Stoney and John Purser Griffith. Readers will recognise Bindon Blood Stoney from Brian Smyth’s article in the last edition of History Ireland. His name is not easily forgotten and belongs in the pantheon of fantastic names from Irish history alongside Hercules Mulligan, James ‘Skin-the-Goat’ Fitzharris and Sitriuc Silkbeard.

Town and country: perspectives from the Irish Historic Towns Atlas may also sound familiar to subscribers of History Ireland, as, in recognition of their loyalty to the magazine, a number of editions included laminated inserts provided by the Irish Historic Towns Atlas, detailing the history and development of places like medieval Dublin, Kells, Carrickfergus and many others. This book explores the interconnection between town and country, discussing the complex and enduring entanglement of the urban and rural from monastic times to the nineteenth century; it also contains reflections on the life and legacy of John Andrews, the innovative historical cartographer who passed away in 2019.

An rud is annamh is iontach (what’s seldom is wonderful), mar a deir an seanfhocal, and while it may not have been wonderful for those involved, Wise’s Irish Whiskey: the history of Cork’s North Mall Distillery recounts what is certainly seldom these days—an Irish whiskey distillery closing down rather than opening up. Virtually no trace of the distillery survives today, yet in 1820–1 no other distillery in Ireland produced more gallons of spirits than Wise did at North Mall, trumping Jameson, Roe and Power. Wise remained Cork’s premier distiller until the middle of the nineteenth century, when increased competition from blended whiskeys alongside unsustainable production costs initiated a decline that was eventually fatal owing to the onset of the Great War and an accidental fire in 1920, consigning Wise’s Irish whiskey to the great bar in the sky.

Coleraine Historical Society, The Bann Disc (Coleraine Historical Society, £10 pb, 76pp, ISBN 9781915199126).

Luke Dineen, A city of strikes: the Cork General Lockout of 1909 (Irish Labour History Society, €9 pb, 70pp, ISSN 1393-9823).

Irish Labour History Society, Tom Johnson 1872–1963, Marie Johnson 1874–1974: seeking no honours (Irish Labour History Society, €12 pb, 136pp, ISBN 9780956052995).

Padraig Yeates, William Partridge 1874–1917: the forgotten leader (Umiskin Press, €24 pb, 138pp, ISBN 9781739156442).

John Cunningham, Francis Devine and Sonja Tiernan (eds), Labour history in Irish history—essays celebrating fifty years of the Irish Labour History Society (Umiskin Press, €28 pb, 453pp, ISBN 9781838111212).

Ronald Cox, Dublin Port chief engineers (Dublin Port Company and Engineers Ireland, €20 hb, 105pp, ISBN 9781399935500).

Sarah Gearty and Michael Potterton (eds), Town and country: perspectives from the Irish Historic Towns Atlas (Royal Irish Academy, €30 pb, 300pp, ISBN 9781911479819).

Barry Crockett and Stephen D’Alton, Wise’s Irish Whiskey: the history of Cork’s North Mall Distillery (Cork University Press, €49 hb, 256pp, ISBN 9781782055754).