By Edel Bhreathnach

One of my earliest memories is of going with my parents to the parish church in Killester, which was dedicated to St Brigit. It held a relic of St Brigit, reputedly part of her skull, which was brought there from Lisbon in 1929 for the church’s consecration. It was enshrined in a reliquary inspired by the medieval shrine of St Patrick’s Bell. This reliquary was stolen in 2012, although the relic itself remains in Killester. A ceremony was conducted in Irish on the Sunday nearest 1 February. It was normally a cold, windswept day, and as children it was not our favourite annual event. No doubt many children of my generation visited wells dedicated to Brigit on similarly cold days and, as in our family, a sibling was named after her. Despite the cold misery of the day, I did not leave Brigit behind and to this day she remains something of a historical enigma to many around the world. Of course, the nature of the popular image of her has changed radically since the 1960s. She has been transformed from a national saint, a representation of all that was virtuous in womanhood, to a feminist icon, Celtic goddess and, increasingly, a healing, nurturing woman with environmental credentials.

A TIME OF CHRISTIAN CONVERSION

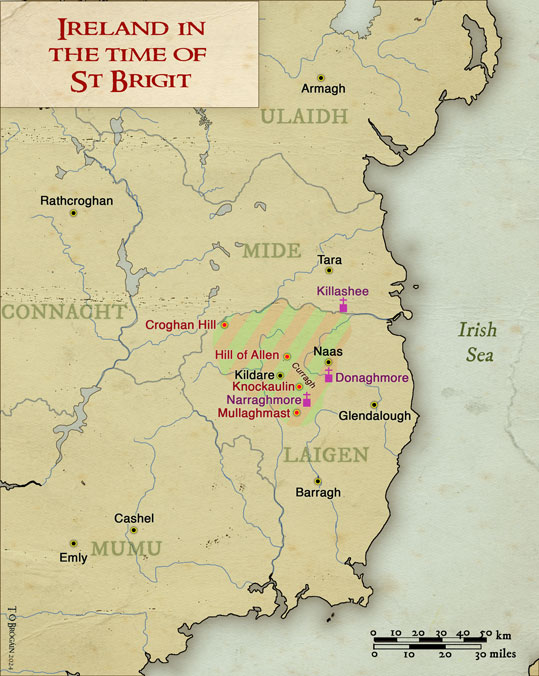

But who was St Brigit? How do we know her story, saint or goddess? The earliest sources to narrate her life and origins date from the seventh, eighth and later centuries. These consist of lives in early Irish and in Latin and a curious poem embedded in the earliest genealogies of the Fothairt, a people who were settled in pockets throughout Leinster but especially between Croghan Hill, Co. Offaly, and the Hill of Allen, Co. Kildare. The Irish annals record that Brigit was born around AD 439 and died around AD 524. These dates are not necessarily reliable, and, for those who do not believe that Brigit was a historical figure, are worthless. Nevertheless, Professor Daniel McCarthy, a leading expert on the construction of the Irish annals, has made a strong case in favour of their authenticity, and has even suggested that her existence was acknowledged in the great monastery of Iona at an early stage.

If Brigit did indeed live at this time, she was born into a period of great change in Ireland. This was when the Irish were going through a religious conversion from a pre-existing religion (or religions) to Christianity. With the new religion came a new language, Latin, and literacy. The process of conversion was not as decisive as the popular narrative relates, of St Patrick singlehandedly displacing druids, chasing snakes away and converting the island in one lifetime. Christianity spread gradually at different rates and by various means, through Christian missionaries, trading networks or familial connections with Roman Britain, western France and even the Mediterranean. The appearance of imported Continental and Mediterranean pottery from these regions on Irish archaeological sites at this time is clear evidence of such extensive contacts with places that were themselves being contemporaneously converted to Christianity. British and Continental missionaries and others, among them the noble Palladius, sent by Pope Celestine from Rome to seek out the Irish believing in Christ in AD 431, were active in Ireland as part of this religious conversion. It seems likely that the inhabitants of the eastern and midland region known as Laigen (modern Leinster), the province where Brigit was born, were converted at an early stage owing to its strong contacts with western Britain.

CHRISTIAN BRIGIT

The lives of Brigit, written more than 200 years after her likely death, are primarily Christian texts. One of the seventh-century Latin lives of Brigit was written by Cogitosus sometime around AD 650–80, with the objective of glorifying Kildare as a powerful monastery with national interests. His famous description of the church with the highly ornate tombs of Brigit and her bishop Conláed set on either side of the monastery’s altar, revered by the nuns and monks of the double monastery and by the select laity, is reminiscent of late antique Christian basilicas housing the shrines of great saints. Whether this is simply a literary trope or a genuine description remains an open question.

PAGAN BRIGIT

What of the ‘pagan’ attributes of Brigit? Many popular theories associate Brigit with a goddess, Brigantia, who was revered among the British people known as the Brigantes. The evidence is not conclusive. The name Brigit includes the element brig– (‘high, exalted’) and could have existed in Ireland separately from Brigantia and the Brigantes. There are other saints named Brigit and Bríg throughout Ireland, and it has been argued that they and their many ritual sites, normally wells, retain the memory of an earlier non-Christian tradition that transferred to a Christian cult. That may be so, but it does not preclude the existence of a historical individual who founded a female community in Kildare.

And it is to Kildare that we must turn to understand the ‘pagan’ and Christian narrative of Brigit. It is often forgotten that Kildare is at the head of the Curragh, one of the most crowded prehistoric funerary landscapes in Ireland. Clusters of Bronze Age barrows and ring-ditches, Iron Age ring-barrows and enclosures, henges and linear earthworks have been identified in this landscape. One of Leinster’s most important prehistoric monuments, Dún Ailinne (Knockaulin), classified as a ‘royal’ site, overlooks the Curragh and, like Kildare, features in the earliest literature associated with the region. Excavations undertaken in the Curragh by Professor Seán P. Ó Ríordáin during the 1940s unearthed burials that might date from as late as the sixth century. We can safely conclude from this evidence that while Brigit may have been busily founding her monastery in Kildare in the late fifth/early sixth century, non-Christian ritual practices were far from suppressed outside the monastery’s enclosure in the Curragh.

Brigit was on the cusp of a great transition in Ireland. One episode in the saint’s Irish life that has been overlooked seems to offer a key to what was happening in Kildare and how the change could have come about in reality. Brigit’s protégé, a nun named Dar Lugdach, expressed a wish to die on the same day as Brigit but the saint insisted that she die a year later, declaring that both of them would share the same feast-day. And so it happened. The joining of the women so closely together infers an effort by the author to weave two traditions into one. Why is Dar Lugdach portrayed as Brigit’s protégé? The answer to this may unravel the goddess from the saint. The name Dar Lugdach means ‘the daughter/devotee of Lugaid’. Lugaid is one manifestation of Lug, the Celtic god of all arts and warfare, known throughout the Continent, Britain and Ireland from personal and population names, place-names and mythology. If Dar Lugdach was a devotee of Lugaid, it is possible that Kildare’s original function was that of a site, perhaps a sanctuary, dedicated to Lug, and that this was tended by women. Brigit and Dar Lugdach may be one and the same individual, or perhaps Brigit replaced a genuine female devotee of Lugaid and inherited her sanctuary but retained it primarily as a female foundation. Alternatively, as Dar Lugdach is listed as Brigit’s immediate successor, perhaps this was how Lug’s devotee was Christianised?

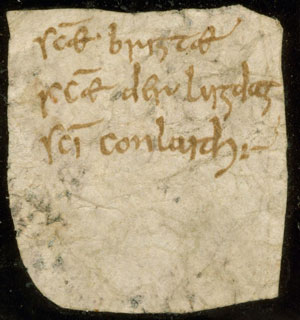

Professor Julia Smith’s important discovery of a vellum label that would have been attached to a relic contained in a small, probably wooden, reliquary in the monastery of Saint-Maurice d’Augune, Switzerland, located on the main Roman road over the Alps from Italy into Gaul, casts a different light on the early history of Brigit and Kildare. This tiny label, or relic authentic, likely to date from c. AD 700 or slightly earlier, reads: s(an)c(t)æ·brigtæ/s(an)c(t)æ derluigdag/s(an)c(t)i conlaith (‘[relics of] St Brigit, St Der Lugdach, St Conláed’). As Professor Smith has remarked, ‘this label challenges reliance on narrative content [i.e. the lives of St Brigit] as the main source for the early history of Kildare’. Clearly, Dar Lugdach was regarded as a saint along with Brigit and her bishop, Conláed, at an early stage.

A DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVE?

If this label reflects an early Kildare tradition, does this enable us to approach Brigit and her foundation from a different perspective? Brigit belonged to the Fothairt, a people who were settled in pockets throughout Leinster and as far north as near Armagh. Their primary function in genealogical and pseudo-historical sources was to protect the kings of Leinster, but perhaps one of their most important functions was to guard the ceremonial landscape of their heartlands, which stretched eastwards from Croghan Hill, Co. Offaly (Crúachan Brí Éile), to the Hill of Allen (Almu) and southwards to Knockaulin (Dún Ailinne) and Mullaghmast (Maistiu). This was the most important land in Leinster, which any king who wished to claim the provincial title had to control. The core of this prized land was the Curragh, with Kildare at its head.

Would it be any surprise, therefore, if Kildare was an early cult site, possibly dedicated to Lug, that became a Christian church at the time of conversion? I have written elsewhere about the possibility that people like the Fothairt—regarded as vassal peoples subject to the dominant dynasties that emerged during the seventh century—retained an important role as defenders of ceremonial landscapes such as Tara, Rathcroghan, Cashel, Emly and others. I would now include the Fothairt among them and argue that the reason that abbesses from among the Fothairt ruled Kildare sporadically until at least the tenth century was not only based on their genealogical association with Brigit but also on the Fothairt’s traditional role as guardians of Kildare and the Curragh, a status that is likely to pre-date its Christianisation. That the Fothairt genealogies also associate them with some of the earliest Christian churches in Leinster such as Killashee, Co. Kildare (Cell Auxilli), Donaghmore, Co. Kildare (Domnach Mór), and Narraghmore, Co. Kildare (Forrach Pátraic), also suggests that they were active in the early conversion of this contested territory.

The inclusion of Bishop Conláed on the vellum label hints at another aspect of the background to Brigit’s life that has been concealed in the existing hagiography. Conláed belonged to the branch of the Dál Messin Corb, a significant Leinster dynasty, to whom St Kevin of Glendalough and a plethora of other prominent early bishops belonged. And furthermore, another branch of the Dál Messin Corb, the Uí Garrchon, whose main residence appears to have been situated at Naas, Co. Kildare (Nás), are recorded as holding the kingship of Leinster until at least the late fifth century. Hence not only was Kildare an episcopal church from its foundation but it was also a royal foundation and remained so until the twelfth century. The rise of the Uí Néill in the midlands and of the Uí Dúnlaing in north Leinster, and of Armagh and the cult of Patrick during the seventh century changed the nature of Brigit’s cult, and her authority moved into another realm that extended beyond Kildare and the lands of the Fothairt. This change is the backdrop to Cogistosus’s life of Brigit, the Vita Prima and Bethu Brigte, in which Brigit shares the stage with Patrick, attends ecclesiastical synods and deals with Uí Néill kings. And yet it should be noted that the first genuine Uí Dúnlaing king of Leinster, Fáelán mac Colmáin (d. 666), whose brother Áed Dub was abbot of Kildare (d. 639), was married to Sárnat of the Fothairt, an alliance replicated so often in which a woman from a vassal people legitimised an incoming dynasty through marriage. Sárnat belonged to the Fothairt settled in the townland of Barragh (Berrech), barony of Forth (Fothairt), Co. Carlow.

CONCLUSION

To sum up, there is so much more that remains to be discovered about the historical St Brigit if we put aside current narratives, which in reality reflect our own modern cultural interpretations. She did exist and she belonged to the Fothairt, an important people who guarded Kildare and the Curragh in the pre- and post-conversion eras. Her seventh-century and later lives are replete with traditions and material of relevance to her, and probably to her predecessors in Kildare, but historically do not reflect the situation in late fifth/early sixth-century Leinster. As to a lesson in reading sources, the entries in the early annals, including the dates of Brigit’s birth and death, will always be open to interpretation. On the other hand, the genealogical sources should be examined for corroborating material. They are such an extensive record for so many different early peoples throughout Ireland that they are an essential tool for understanding what is a shadowy period in medieval Irish history.

Edel Bhreathnach is the author of Monasticism in Ireland, AD 900–1250 (Four Courts Press, 2024).

Further reading

E. Bhreathnach, ‘Clinging to power: the role of vassal peoples in early Ireland’, Discovery Programme Reports 9 (2018), 5–17.

T.M. Charles-Edwards, ‘Early Irish saints’ cults and their constituencies’, Ériu 54 (2004), 79–102.

D.P. McCarthy, ‘The chronology of St Brigit of Kildare’, Peritia 14 (2000), 255–81.

J.M.H. Smyth, Relics and the insular world, c. 600–c. 800, Kathleen Hughes Memorial Lectures 15 (Cambridge, 2017).