By Peter Gray

The collapse of Protestant radicalism in Ulster in the wake of the 1798 Rebellion has attracted much historical discussion. From being an epicentre of United Irish activity in the 1790s, Belfast and its rural hinterland appeared to have abandoned such enthusiasms and reoriented themselves to a conservative unionism over the following century. The extent to which the rebellion was truly ‘forgotten’ in Ulster has been persuasively challenged by Guy Beiner in his recent book Forgetful remembrance; nevertheless, it is undeniable that an array of overlapping forces combined over time to ‘squeeze out’ any public expression of United Irish politics among most Ulster Protestants. These included the trauma of the repression of the rebellion itself, along with perceptions that it had taken a sectarian turn elsewhere; the assertive expansion of the Orange Order in the wake of 1798; the rapid development of Belfast industry within the free-trade area created by the 1801 Act of Union; the growth of evangelicalism within the Protestant churches, which was connected to conservative politics by leading clerics such as Dr Henry Cooke; and the anxiety provoked by the emergence of Catholic majoritarian mass politics led by Daniel O’Connell. In this context, conservative landed élites reasserted their dominance in the countryside, and the urban middle classes tended to back away from the legacies of popular republicanism.

AN UNLIKELY CANDIDATE FOR RADICAL LEADERSHIP

This is not, however, the whole story. Over the decades that followed the Union, radicalism did reassert itself in the north, not just among the disaffected Catholics of the province but also among many Protestants, in reaction against the new political dispensation. If this revival by necessity took on a different form from that of the 1790s, it nevertheless looked back to eighteenth-century models and continued to rely heavily on Presbyterian traditions of social and political radicalism. The renewed movement found a figurehead and inspiration between 1830 and 1861 in the person of William Sharman Crawford, and his memory would continue to be cited by Ulster liberals through to 1900 and beyond.

Sharman Crawford was an unlikely candidate for radical leadership. An Anglican landowner, he had inherited estates in counties Down and Meath in 1803 and added to his substantial holdings with the bequest of his father-in-law’s estates at Crawfordsburn and Rademon in 1827. By 1830 he had emerged as a leading figure in the ‘independent’ political group in Down, which challenged the control of the dominant Hill (Downshire) and Stewart (Londonderry) families. Crawford himself stood for the county in the 1831 election as a ‘radical’ supporter of the Whig government’s parliamentary reform bill, but defeat by the landed interest left him frustrated by the highly undemocratic structures of politics and conscious that only the mobilisation of a tenant electorate around agrarian reform could counter the combined weight of deference and sectarianism in the countryside.

His campaigning had, however, impressed the middle-class liberal leadership in Belfast, and he was invited to stand in the first contested election for the borough in 1832, alongside Robert James Tennent, nephew of the former United Irishman William Tennent. Their joint campaign stressed the issues of reform of the franchise and the introduction of the secret ballot, the abolition of colonial slavery and Irish tithes, and the removal of the corn laws, which kept food prices high. Crawford believed it important to canvass both Catholics and the broader working class in the town and emphasised his commitment to social reform, but only middle-class ratepayers had the vote and large sections were alarmed both by the rising threat of O’Connellism and by the inherited association of Tennent and his allies with the United Irishmen. To counter this, the Belfast radicals appealed to the memory of the Volunteers of 1778–93, a movement which in the north had embodied patriotism and political reformism without the problematic association with revolution. Crawford’s record was strong in this respect: his father, Colonel William Sharman, had chaired the 1783 and 1793 Volunteer Dungannon Conventions and had been the presiding officer at the 1791 Belfast parade to celebrate the fall of the Bastille (his father-in-law John Crawford had done the same in 1792). Pride in the Volunteers was still a potent force in Ulster in the first half of the nineteenth century, and Sharman Crawford was its living embodiment. This was not enough, however, to swing the 1832 election in Belfast, with the radicals losing out to moderate candidates more in tune with bourgeois anxieties. Belfast politics over the following decades would see seats swing between the Tory and Whig parties, but by the time R.J. Tennent was finally elected in 1847 he had shifted towards the political centre.

FOR AND AGAINST O’CONNELL

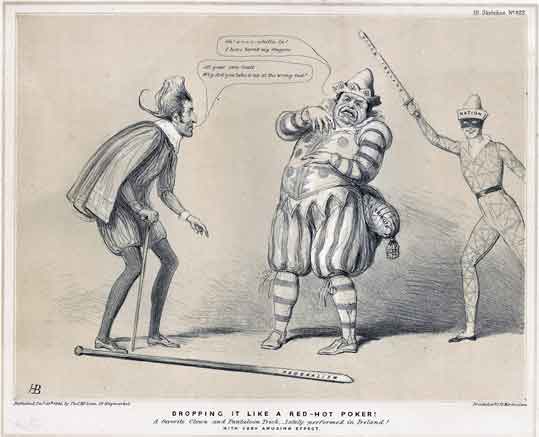

In contrast, this second setback pushed Sharman Crawford into exploring alternative alliances to attain radical reform. Impressed by O’Connell’s success in achieving Catholic Emancipation through peaceful mass mobilisation in 1829, he opened discussions with the Catholic leader and published two pamphlets in support of Catholic demands and Irish self-government in 1833. O’Connell initially welcomed his northern admirer to the Repeal fold and found him a safe seat at Dundalk in 1835. Relations quickly soured, however, as Sharman Crawford came to publicly criticise the Liberator’s social conservatism on both the Poor Law and tithe questions and to challenge his autocratic leadership style. In 1837 he was deselected and returned to Crawfordsburn, from where he penned numerous public letters to the press attacking the ‘Liberator’. Never a whole-hearted Repealer, and conscious of northern Protestant suspicions of nationalism, Sharman Crawford articulated ‘federalism’ as an alternative that might reconcile Irish national feeling with British sovereignty and the benefits of free trade. O’Connell briefly toyed with the scheme in 1844, only to abandon it under pressure from his Young Ireland critics, while most Ulster Protestants remained indifferent. Federalism would only gain wider traction when revived by Isaac Butt under the names of ‘home government’ and ‘home rule’ in the 1870s.

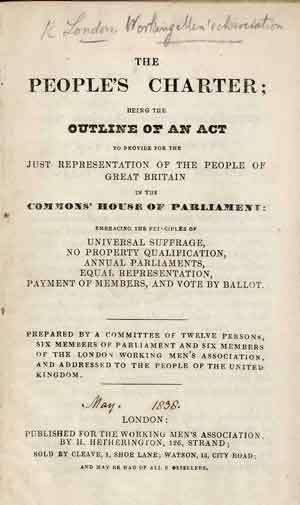

Sharman Crawford now sought to build a new entente with British democratic reformers; he developed a friendship with the London radical William Lovett and signed his manifesto, ‘The People’s Charter’, in 1838. As his attempt to create a pro-democracy body in Belfast with the Ulster Constitutional Association failed in 1840–1, he was drawn increasingly towards British Chartism. Invited by local Chartists and liberals to stand for the industrial borough of Rochdale in 1841, he was elected and held the seat until 1852, using the platform to advocate democratic and social reforms for the whole United Kingdom while also retaining his Irish agendas.

‘THE LEAGUE OF NORTH AND SOUTH’

Always widely praised as an ‘ideal’ landlord who sought co-operative relations with his tenants, Sharman Crawford developed an agrarian reform platform and introduced his first parliamentary land bill in 1835. By the mid-1840s his position had strengthened to a full defence of tenant right (as embodied in the ‘Ulster custom’ of recognition of a tenant’s financial stake in his holding) along with curbs on evictions and adjudication of a ‘fair rent’. The onset of the Famine was to turn this campaign into a mass movement, as tenant farmers, even in the less-distressed parts of Ireland, faced destitution and the growing threat of wholesale eviction. His advocacy in parliament, the press and public meetings helped stir a national agrarian movement from 1847. In Ulster the movement attracted the support of lawyers and journalists such as Samuel Greer and James McKnight and enthusiastic engagement from large sections of the Presbyterian clergy and laity. Despite setbacks associated with State coercion and the polarisations triggered by the Young Ireland rebellion and an Orange Order reaction in 1848–9, the tenant-right leadership worked to exclude religious antagonisms from their platform and rebuilt the movement in the lead-up to the formation of the Irish Tenant League in summer 1850. Their success, against the odds, in creating a national reformist alliance with mass support justified at least for a time Charles Gavan Duffy’s labelling of it as ‘the League of North and South’.

Although Sharman Crawford stressed the pragmatic case for legalising tenant right, he was also prepared to use radical rhetoric—denouncing his fellow landlords as social parasites and calling for measures to provide employment and welfare entitlements to the labouring poor as well as tenant farmers. In 1852 he gave up his English seat and stood again for County Down on a tenant-right ticket. The campaign was bitter and punctuated by violence, with the Presbyterian and Catholic clergy supporting Sharman Crawford at public meetings across the county. Despite great radical optimism, a combination of landed and Orange intimidation and fear-mongering about a ‘United Irish’ revival, in the continuing absence of the secret ballot and with a restricted electorate, again consigned him to defeat. Despite this setback, and the splitting of the League over prominent defections to the new liberal coalition government in early 1853, Sharman Crawford and his northern tenant-right allies remained politically active through the 1850s, retaining significant popular support. Regarded as an honest friend by the Belfast labour movement, one of his final public appearances before his death was at a working-class rally in the town at which he challenged the ‘oligarchy of the landed and moneyed interest’, demanded democratic enfranchisement and urged Belfast to throw off the curse of sectarianism and reclaim its place at the forefront of Irish radicalism, as in the era of the Volunteers.

HIS IDEAS SURVIVED

Following his death in 1861, Sharman Crawford was memorialised by a monument erected at his tenants’ expense at Rademon. His ideas also survived to shape the revival of Ulster liberalism in the 1870s and inform the belated conversion of William Gladstone and his Liberal party to Irish land reform from 1870. His son James succeeded where he had twice failed in gaining election for Down in 1874 (aided by the introduction of the secret ballot in 1872). This revival was ruptured by the polarisation over Home Rule in 1885–6, which sharply divided his family (his daughter Mabel praising him as an early home-ruler, his son Arthur founding the Belfast Liberal Unionist Club and his grandson Robert Gordon becoming a Unionist MP and UVF officer). Nevertheless, ‘Sharman Crawfordism’ persisted as a minority strand in Ulster politics, inspiring the agrarian radicalism of T.W. Russell at the turn of the century and laying foundations for the gradual recovery of a liberal-radical alternative to the politics of sectarian polarisation in Northern Ireland from the 1960s.

Peter Gray is Professor of Modern Irish History at Queen’s University, Belfast.

Further reading

P. Gray, William Sharman Crawford and Ulster radicalism (Dublin, 2023).