By Brian Hopkins

By the 1860s, Ireland was emerging from the devastation of the Great Hunger into an era of relative agricultural prosperity for some that coincided with a revival of Anglo-Irish landlordism. Support for or against landlords became increasingly more pronounced in elections to two-member seats during this decade. Tenant farmers were generally not predisposed to defy their landlords at the ballot box, not only because of a change in their fortunes but also because their votes were a matter of public record. Nevertheless, there were instances in the 1860s where such reluctance was not evident. The 1865 general election in County Louth is a case in point.

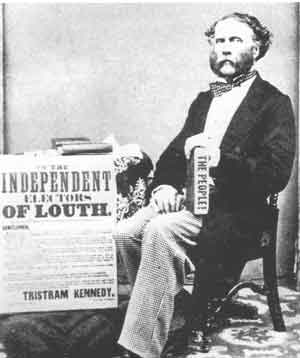

THE CANDIDATES

Donegal-born Tristram Kennedy first appeared on the Louth political landscape in 1852 as a representative of the Independent Irish Party (IIP). He and Chichester Fortescue were elected at the expense of John McClintock and his Tory running mate. Having lost his Louth seat in 1857, standing again for the IIP (now in its death throes), Kennedy tried his luck in the King’s County (Offaly) 1859 general election without success. He then kept his political powder dry until the 1865 Louth by-election, now as a Liberal. By this time he had gained the support of the local clergy and backed the disestablishment of the Church of Ireland and tenant rights. He was viewed, however, with suspicion by Archbishop Cullen, who was unsure of Kennedy’s commitment to educational reforms that were being pursued by the Catholic Church. Notwithstanding Cullen, Kennedy was narrowly elected in the by-election and stood again in the general election three months later.

Hailing from Carlingford and from one of the leading families in the county, Chichester Fortescue held his seat from 1847 to 1874. A political heavyweight on both sides of the Irish Sea, he served in various Westminster posts under the Palmerston administration and those of Lord Russell and William Gladstone while retaining his seat in Louth. By 1865 he had nailed his colours to the mast of the Liberal Party, now becoming the most eminent Irishman in the upper echelons of the party. Like Kennedy, he dedicated himself to achieving reconciliation between Catholics and independent liberals. Initially he appeared to be opposed to tenant rights; as the 1865 election approached, however, he attempted to promote a land bill that would ensure such rights, but the effort was eclipsed by the parliamentary focus on the Reform Bill. As a consequence, he resigned from his ministerial post in June 1866.

Frederick John Foster was a scion of an influential County Louth family of the Ballymascanlan sept. He served as a justice of the peace and in 1845 he became deputy lieutenant and high sheriff for Louth. He stood as a Conservative candidate in the general election of 1859, achieving only 23 votes. It seems that Foster was nominated as ballast to counterbalance the threat offered by the two Liberal candidates. His Tory running mate John McClintock suffered a narrow loss, with Fortescue and Richard Montesqieu Bellew securing the seats.

John McClintock, a dyed-in-the-wool Tory, was a progeny of a prominent Louth family that owned extensive agricultural land in and around the village of Drumcar. He assumed the post of high sheriff of the county in 1840, and first stood as a Conservative in the 1841 general election but had to wait until 1857 before he was elected MP. Two years later he lost his seat. To all intents and purposes, McClintock had sunk his political credibility below the Plimsoll line.

We now turn to the ‘dynamic maverick’ who could not avoid adding fuel to what proved to be a rambunctious contest between Liberals and Tories in the 1865 general election: Vere Foster.

VERE FOSTER—PHILANTHROPIST AND EDUCATIONALIST

Vere Foster was born in Copenhagen to a rather distinctive family of politicians and diplomats: his grandmother formed a ménage à trois with the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire, while his father, Augustus, killed himself by slitting his throat. They were also Irish landowners, with an estate at Glyde Court near Ardee and elsewhere in County Louth. Following his father’s death, Foster made his first visit to the family estates in Louth in 1847 at the height of the Great Hunger. What he saw and learned turned him into a champion of all things Irish. History has dubbed him a philanthropist and educationalist.

His considerable family inheritance allowed him to fund the needs of emigrants to North America and elsewhere, having himself experienced the misery of coffin ships on three transatlantic trips and in the process coming close to death. Foster was especially concerned with the plight of female emigrants and in 1852 established the Irish Female Emigration Fund.

His interventions in the field of education still resonate today, based on his experience of witnessing the pitiful state of national schools in County Louth and elsewhere. He paid in part for the building and refurbishment of hundreds of schools in Ireland, meeting opposition from the Catholic clergy backed by the ultramontane Cullen. His other achievements include the publication of books on landscape painting and handwriting.

Given his ongoing and extensive campaigns on behalf of the poor, Foster must have had the constitution of a triathlete. Coming from a family steeped in politics, perhaps for relief he found it hard not to constrain his dabbling in the political arena. One such occasion was during canvassing in the 1865 County Louth general election.

CANVASSING IRISH-STYLE AND FOSTER’S INTERVENTION

Perhaps quintessentially Irish was the political influence of the clergy. In the 1860s the Irish clergy were polarised into two factions: one led by the ecclesiastical imperialist Cullen, who was inclined towards moderate liberals, and the other by Archbishop McHale of Tuam, whose sympathies lay with the nationalist, but not Fenian, movement. This distinction was mirrored by parish priests, who tended to support moderates, in contrast to curates, who could be disposed towards candidates holding more extreme views. Occasionally, priests would preach fire and brimstone from the pulpit, threatening those who opposed their preferred candidate with exclusion from the sacraments.

Electors and agricultural workers would sometimes engage in a ‘donnybrook’. Such was the case in the 1852 Louth general election: during a meeting of the tenant rights club in the mid-Louth town of Dunleer, Kennedy’s carriage was pounded by missiles, clergymen were threatened and one of their number was knocked to the ground. Fuelled by drink, the violence was instigated either by the Bellew family or Phillip Callan, Fortescue’s agent. Fortescue won the election and Kennedy scraped into the second seat at the expense of McClintock.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the front pages of local newspapers often devoted space to individuals to promote their favoured candidates. In the general election of 1865, Vere Foster availed himself of the opportunity to publish his preference. Printed in the Drogheda Argus and other newsprint outlets, on 8 July his long-winded diatribe denounced the candidature of McClintock and endorsed those of Fortescue and Kennedy with the words: ‘Vote for Kennedy and Fortescue … down with McClintock, down at the foot of the poll’. His letter included a somewhat cryptic suggestion that McClintock might be an anti-Catholic bigot. This oblique accusation triggered a rambling response published in the Drogheda Argus from 114 signatories identifying themselves as Roman Catholic farmers, tradesmen and labourers living on McClintock’s Drumcar estate (one of the signatories, Owen Verdon, is the author’s great-grandfather). Referring to him as ‘Honest John McClintock’, the signatories emphasised, among other things, that he was not a bigot who hated Catholics, as witnessed by his voting record in parliament and a contribution of £10 towards the building of the local school.

Why was Foster so critical of McClintock and supportive of Fortescue and/or Kennedy? The most straightforward answer is that he recognised that both men shared his liberal and non-sectarian views. If the preceeding 1865 by-election is any indication, then his first choice would have been Kennedy, whom he valorised in both writing and speech-making for his radical policies during that election.

THE OUTCOME

On a voter turnout of about 48%, Fortescue and Kennedy garnered 600+ votes each, with the former coming first with a margin of just 21 votes. As for ‘Honest John’ and fellow Conservative Frederick John Foster, they accrued the miserly totals of eight and six votes respectively. As Vere Foster had urged, McClintock was ‘down at the foot of the poll’.

It is tempting to infer that Foster’s intervention led to McClintock’s disastrous result. To arrive at a satisfactory interpretation, however, the by-election and general election need to be compared. In the by-election, held only three months previously, the turnout was 79%, with McClintock trailing by 79 votes. Thus it seems that a substantial number of electors were deterred from casting their votes in the general election—almost half, in fact. Typically, by-elections serve as a warning signal for candidates, with a more telling vote being expressed in a subsequent general election. In that scenario, Foster’s published letter could have carried some weight with voters when it came to the general election. Certainly, the epistle of support for McClintock by some of his Drumcar residents does not seem to have had the desired effect.

To conclude, the 1865 general election was a significant turning-point in Irish political history, as it paved the way for the rise of Home Rule and nationalist politicians and the dissipation of the Irish Liberal and Tory parties. That would have pleased the dabbling maverick Vere Foster.

Brian Hopkins is Emeritus Professor of Psychology at Lancaster University.

Further reading

B. Colgan, Vere Foster, English gentleman, Irish champion 1819–1900 (Belfast, 2001).

C. Kenny, Tristram Kennedy and the revival of Irish legal training 1835–1885 (Dublin, 1996).