By Emma Quinn

A March 1931 article in the Irish Examiner announced that a ‘solemn decree protesting against “so-called sexual education of youth” had been issued’ by the Vatican. The same year, the Carrigan Committee submitted its final report on sexual behaviour in the Irish Free State; this provided a plan for legislative reform to combat rising rates of sexual crime against young women and children, prohibit the sale of contraceptives and, as argued convincingly by James M. Smith, establish the ‘origins of Ireland’s containment culture’. The report’s influence on Irish policy against subversive sexual behaviour has been highly discussed, and rightly so—the impact of mother and baby homes, confinement, Magdalen asylums and other Catholic Church-operated and State-endorsed forms of sexual control continues to affect the country today.

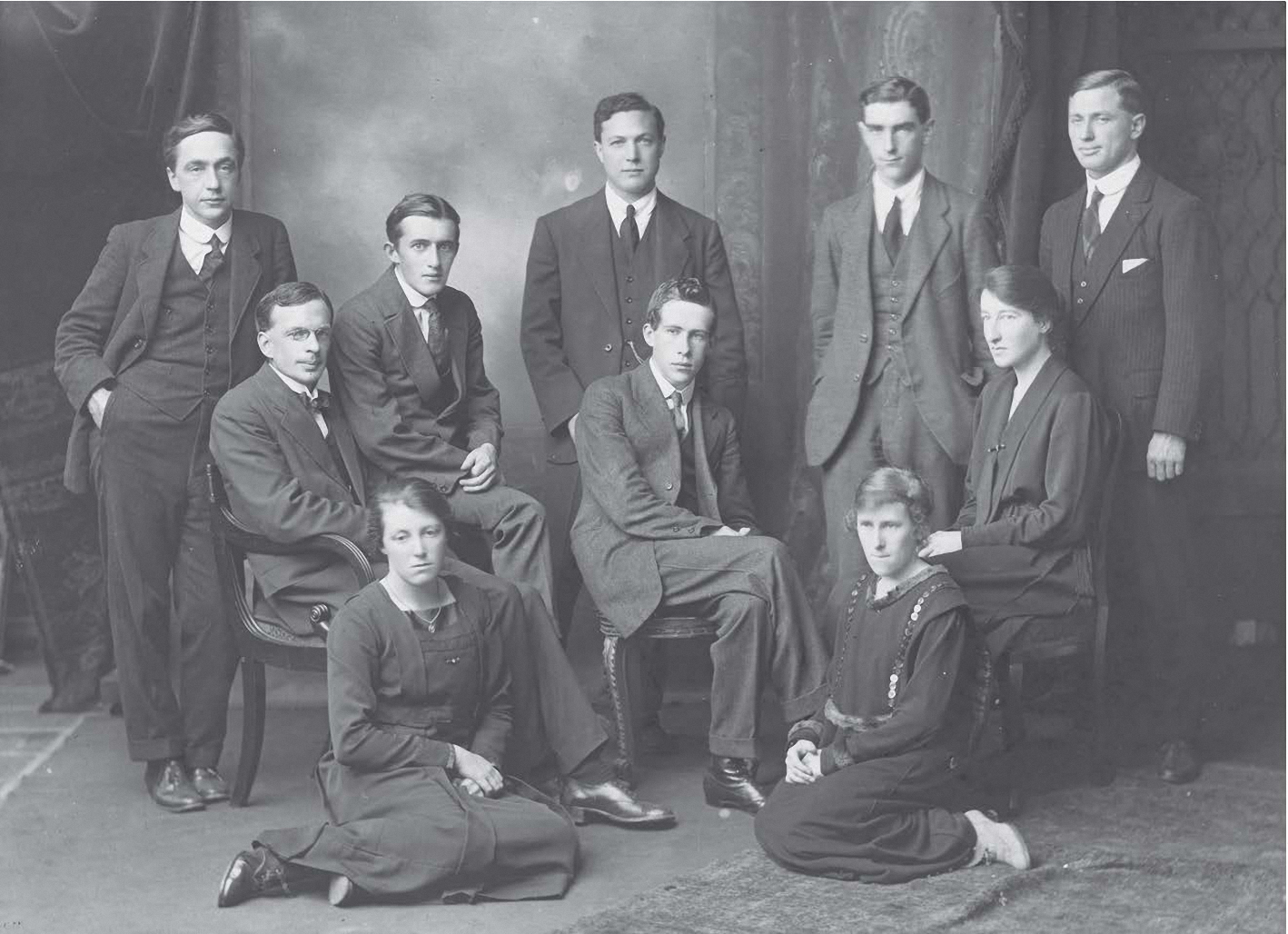

FEMALE WITNESSES

The Carrigan Committee was appointed to update the 1880 and 1885 Criminal Law Amendment Acts on social and moral issues, especially regarding underage prostitution. A surprising number of the witnesses called to testify in front of the committee were women—eighteen out of 29. They came from a variety of fields: healthcare, charitable work, unions and women’s rights organisations. The final report, however, explicitly alluded to the women participants only once, dramatically underemphasising their role as experts and suppressing their suggestions, especially regarding sexual education and rehabilitation for marginalised people. The various paths taken by these women to become highly visible professionals and experts aided their value as witnesses, yet ultimately failed to give their suggestions enough weight to be enacted in the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1935.

The Carrigan Report was finalised in August 1931 after seventeen meetings. The compiled results revealed extensive evidence of sexual crimes against young women and children, rising rates of illegitimacy, and a general disconnection between Catholic moral purity and reality. In response, the Committee provided a set of legislative proposals, including raising the age of consent to eighteen, increasing the scope for prosecuting sexual crimes and prohibiting contraceptives, as well as generally increasing fines and sentences for sexual crimes. The Carrigan Report provided a description of attitudes and practices surrounding sex while also formulating a response that would align with Irish national identity, which increasingly centred Catholic values of moral purity.

One might assume that the finalised report reflected the opinions of the majority of the witnesses. However, while most witnesses were women, their contributions were barely mentioned, and their proposed solutions differed significantly from the punitive focus of the report’s suggestions. These women were active practitioners and eyewitnesses who interacted closely with those whose lives would be most affected. This direct knowledge made them more likely to question the current structure and imagine alternative solutions. They envisaged a more forgiving future for people who strayed from strict behavioural standards. Many suggested that educating young women about sex and diminishing the stigma attached to unmarried mothers would lessen the severe prejudices against single mothers, their children and victims of sexual violence. They acknowledged that women were often unwilling to come forward as victims because of the stigma surrounding sexual immorality, and that education and rehabilitation would be more suitable responses than punishment.

MALE WITNESSES

Most of the men who were called as witnesses were clergy (six), while others included Eoin O’Duffy, commissioner of the Garda Síochána, and other representatives from the justice system or charitable organisations. Many male witnesses were involved in either defining moral standards of behaviour as religious leaders or enforcing these standards as members of law enforcement agencies. As a result, their testimonies focus primarily on perceived sources of moral degeneration such as dancehalls, conflating them with rising rates of illegitimacy. For the male witnesses, the core issue was inadequate punishment and containment of sexual knowledge. Their solutions reflected their perspectives as enforcers of Irish Catholic morality.

James M. Smith notes that institutionalisation was still central to the women’s suggestions and points out that, given what is known about the conditions within many mother and baby homes, the women’s ideas were complicit in creating a harmful system. The horrendous suffering inflicted by these homes is undeniable, but it is unfair to blame these women for massive failures in government oversight and regulation that they could not have predicted and which they were certainly not envisaging for their proposed system. Instead, they hoped to provide a safe place for unmarried mothers and their children so that they could avoid the much more traumatic consequences—such as emigration, prostitution and/or incarceration—of a society that had little tolerance for sexual transgressions. The report did endorse institutional provision as a solution to contain Ireland’s social ills, which allowed a culture of silence around improper sexuality to bloom. It was that cultural silence that allowed extensive abuse to persist, not the women who were hoping to create safe places for young women. As with much of their testimony, the nuance of their perspective on institutionalisation was occluded in the final report.

TRAIL-BLAZING WOMEN

Given the narrative that Irish culture in the 1920s and 1930s became increasingly conservative, the presence of so many women in public professional roles seems out of place. These women emerged from a more liberal attitude stretching back to the late nineteenth century, when Irish medical schools became the first in the United Kingdom to admit women as students, while other fields like policing and political organisation welcomed women during the revolutionary era. These women witnesses were the result of various paths to public participation opening for women in the 50 years before 1930. Much of the initial trail-blazing for women in public roles was done by religious sisters. According to scholar Siobhan Nelson, nuns altered the public perception of nursing from being an unskilled job for poor women ‘into an uplifting task for good women’. Nuns offered a path for other women to enter these spaces as nurses, doctors, volunteers and charitable administrators.

The late nineteenth century also saw the relaxation of restrictions against women studying at universities. The number of women participating in third-level education increased steadily through Irish independence and peaked in the 1920s before declining sharply, not surpassing those heights until the 1970s. The growing cultural ideal of women remaining within the private sphere as wives and mothers caused this decline, which also affected constitutional rights. For example, citizenship rights such as jury service were eroded in 1924 and 1937, a public service marriage bar was enacted in 1932, and the 1937 Constitution cemented the place of the woman within a domestic sphere.

Four of the women witnesses were doctors: Ita Brady, Angela Russell, Delia Moclair and Dorothy Stopford Price. Laura Kelly argues that the Kings and Queens College of Physicians in Ireland (KQCPI), as the first institution in the United Kingdom to allow women to take licensing exams in 1877, was open to admitting women for several reasons, including a more liberal attitude towards women in higher education and the significant amount of income accruing from the student fees paid by women. The KQCPI became a ground-breaking institution in terms of gender inclusion, licensing 24 of the first 26 women listed on the Medical Register.

While women were admitted as students earlier than elsewhere in the United Kingdom, that did not mean that their admission was unnoticed or universally endorsed. Female medical students were often considered aloof or cold when compared to their male compatriots, and the field of medicine was deemed a ‘masculinising’ force for women students. Additionally, female students were not allowed to stay in the room for lectures on sexual health and attended a separate anatomy dissection from male students.

ARGUED FOR SEX EDUCATION

Following graduation, women doctors worked across a variety of specialties, although they were most likely to work in general practice, general hospitals and public health. Far from being confined to a separate sphere of practice, women doctors would have been very much aware of the medical consequences of the issues discussed in the Carrigan Report. Lindsey Earner-Byrne argues that the religious affiliations of most medical institutions in Ireland made healthcare policy subject to religious and political manipulation. She points to an alliance between the Church and medical providers that adopted a firm stance against birth control of any kind, including advising mothers to avoid additional pregnancies for their own health. Women doctors existed within this system and would have given medical advice in this context; three of the doctors testified that enhanced sex education for women and girls was necessary, pointing to extremely young mothers and the tendency for girls released from the industrial school system to become sex workers. These women pushed back against Church pressure by arguing in favour of sex education, likely owing to their firsthand experiences with the system’s evils. For example, doctors were regularly called as witnesses in criminal trials against women who committed infanticide.

These women’s careers did not preclude political engagement and participation. As graduates of higher education who most likely came from middle-class backgrounds that could afford school fees, they were also political and community leaders. The breadth of women’s political organisations represented by the female witnesses was significant—the Irish Women Doctors’ Committee (IWDC), the Irish Women Citizens’ and Local Government Association (IWCLGA), the Irish Women Workers’ Union (IWWU) and the Sectional Committee for Women Police and Patrols within the National Council of Women of Great Britain (NCWGB).

These organisations were all founded in the decades immediately preceding independence. They aligned with the growth of trade unionism in the late nineteenth century, alongside the perhaps most notorious Irish union, the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU). Furthermore, they were created because the growing numbers of working women wanted unions that would advocate for their interests. These witnesses campaigned for education and rehabilitation for young women, displaying a level of solidarity and understanding of the women’s experiences that is not present in the men’s testimony. This solidarity is central to the philosophy of these women’s organisations.

WOMEN IN CHARITABLE WORK

Some leading members of these organisations were part of the third group represented among the women witnesses: urban, educated, middle-class women who participated in political organisations and charity administration. As with healthcare, nuns helped to make charitable work a respectable activity for women, especially the middle and upper classes who did not need to work for money but did want to participate in the public sphere. Some women who worked in charity administration overlapped with the membership of organisations like the IWCLGA, although, unlike the multidenominational membership of the former, charities almost exclusively operated on sectarian religious lines. Women and men both participated in charitable work, but their experiences were quite different. While priests and laymen were committee members and raised funds, laywomen and nuns oversaw the day-to-day work of running the organisations. This immediacy gave women a very direct understanding of the personal and structural experiences that led people to need charitable aid.

The charitable organisations represented by Carrigan Committee women witnesses included some official state institutions such as the Lock Hospital, the Magdalen Asylum and the Dublin Union Committee, highlighting the pre-existing dependence on containment as a solution to social ills. The women representing these organisations saw at first hand the harmful effects of incarceration on young women, which points to another reason why they supported opportunities for rehabilitation rather than the harsh realities of the system in place. Therefore, like the women doctors and union representatives, the women who testified on behalf of charitable organisations understood the harm wrought by the culture of containment that defined how vulnerable women and children were treated within the Irish healthcare and welfare systems.

Many of the worst ills discussed by women witnesses were removed from the Carrigan Report, as was their endorsement of education and rehabilitation over incarceration and punishment. While the women’s status as experts was recognised enough for them to be asked to testify, ultimately the perspective of the male witnesses shaped the final recommendations of the report. Strong gender roles and moral laws regarding sexual behaviour were key to preserving the power of Church and State, and so men had little interest in rehabilitating women who (consensually or otherwise) broke the rules surrounding sexuality. Instead, by containing and limiting the knowledge of widespread sexual abuse, assault and trauma, the Church and the State enforced a powerful national image of Ireland defined by religious fervour and sexual purity. This cover-up led to extensive abuse, absence of justice and a culture of silence, the after-effects of which Ireland is still grappling with today.

Emma Quinn is a librarian and Assistant Professor at St John’s University in Queens, New York.

Further reading

- Earner-Byrne, Mother and child: maternity and child welfare in Dublin, 1922–60 (Manchester, 2013).

- Kelly, Irish women in medicine, c. 1880s–1920s: origins, education and careers (Manchester, 2012).

- Nelson, Say little, do much: nursing, nuns, and hospitals in the nineteenth century (Philadelphia, 2001).

J.M. Smith, Ireland’s Magdalen laundries and the nation’s architecture of containment (Notre Dame, 2007).

This is an edited version of one of the winners of the 2023 Irish Legal History student essay prize. Information on the 2025 prize here: https://www.irishlegalhistorysociety.org/?page_id=1464.