By Pat Poland

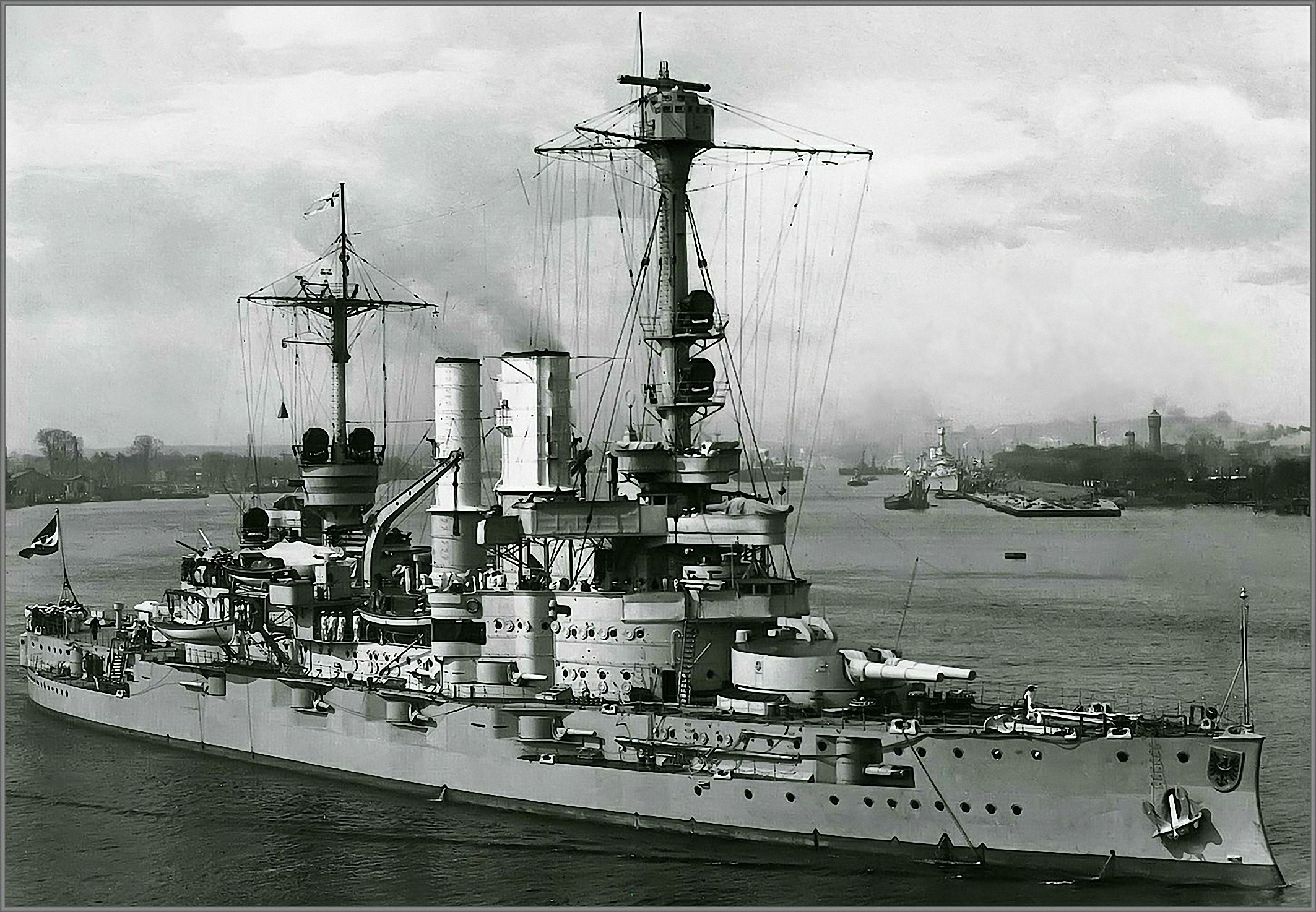

In the early hours of the morning of 1 September 1939, the German pocket-battleship Schleswig-Holstein quietly entered the mouth of the River Vistula near the city of Danzig (present-day Gdansk in Poland), ostensibly on a friendly visit. The unsuspecting Polish garrison on the island of Westerplatte allowed the battleship to sail deep within its defences. Then, at precisely 4.47am, the Germans executed the code-word ‘Fishing’ and opened fire at the island with their massive 11in. guns. Elsewhere, thousands of German soldiers were pouring over the border into Poland. The Schleswig-Holstein was joined by her sister ship, the Schlesien, and their overwhelming fire-power remorselessly bombarded the Westerplatte fortifications. The gallant Polish defenders managed to hold out for five days.

Six months earlier, when the Schlesien sailed into Cork Harbour, the lord mayor, Alderman Jim Hickey TD, had refused to extend to the ship’s officers and crew the courtesies usual in such circumstances. Why?

TOXIC VATICAN/NAZI RELATIONS

In 1939 relations between the Vatican and Nazi Germany were toxic, despite the so-called Reichskonkordat agreed in the dying days of the Weimar Republic in an attempt by the pope to secure the rights of the Catholic Church in Germany. Pope Pius XI, however, became an outspoken critic of Nazi ideology, culminating in the encyclical Mit brennender Sorge (‘With deep anxiety’), written in German. Infuriated, the Nazis responded with mass arrests of clergy and the closure of church presses, events that were widely reported in the international press.

A fortnight before the German battleship’s visit to Cork, the Catholic world was saddened by the announcement, on 10 February 1939, of the death of Pius XI. The Cork Examiner devoted several pages, framed in black, to the event. The German News Agency was less deferential, however, describing the late pontiff in disparaging terms. For Lord Mayor Hickey, a staunch Roman Catholic, this was the last straw. For him, the logic was simple. The pope was Christ’s vicar on Earth, and whoever insulted the pope by definition insulted Christ. His mind was made up. When the Germans arrived in Cork he would refuse to meet them.

JIM HICKEY

Jim Hickey was a native of Ballinagar in the north of the county, one of twelve children. At the age of 27 he moved to Cork and secured employment with the City of Cork Steam Packet Company, later moving to John Daly and Co. He joined the Labour Party and became a trade union official. Now, in February 1939, the 53-year-old Hickey was about to make the most controversial decision of his political career, a decision that would grab international headlines and be reported around the world. And Nazi Germany was not pleased.

From the mid-1930s, the German high command and secret service began to gather intelligence on the fortifications of these islands for the coming war with Britain, which they deemed inevitable. It was envisaged that their Fall Grün (Case Green), the invasion of southern Ireland, might be included in those plans. For hundreds of years military strategists had been aware of the adage that ‘He that would England win must with Ireland first begin’. It is not unreasonable to assume that the newly reconstructed German Navy, the Kriegsmarine, was involved in intelligence-gathering during their many ‘courtesy calls’ to various foreign ports. Cork was not their only pre-war visit to Éire. In April 1937 the Schleswig-Holstein sailed into Dún Laoghaire harbour on a five-day visit. On that occasion every courtesy was extended to the Germans.

FROSTY RECEPTION

At seven o’clock on the morning of Saturday 25 February 1939, the Schlesien, with her complement of over 900 of all ranks, steamed into Cork Harbour on a week’s visit. She came, according to her press release,

‘… on the order of the Führer, Adolf Hitler, and the Greater German Reich, as a harbinger of peace, to find new friends, and to confirm and deepen friendship with old and true friends. We come to understand and get acquainted with your nation with all her sorrows and joys.’

The ship moved into the inner harbour at around eight o’clock, and as she passed beneath Fort Carlisle (now Fort Davis) fired a salute of guns. The Irish responded with a full salute of 21 rounds. As a portent, perhaps, of the frosty relations with the Cork City authorities that were imminent, her captain—Kapitän zur See Lindenau—rashly chose to ignore the Harbour Commissioners’ pilot and the anchorage that had been indicated to him between Deepwater Quay and Haulbowline. Instead, he dropped anchor close to the Spit Bank lighthouse, two miles from Cobh pier. Shortly after the ship’s arrival, she was boarded by Capt. Power, liaison officer from Army GHQ in Dublin, the German chargé d’affaires, Herr Thomsen, and the local German consul, Mr O’Keeffe. When the party arrived back on shore, it was obvious to the waiting reporters that something was wrong. Capt. Power refused to answer any questions and directed all enquiries to the Government Information Bureau. All the others would say was that several social visits provisionally arranged had been cancelled.

Lord Mayor Hickey, however, had no intention of beating around the bush with his reason for refusing to meet the Germans. In a statement to the Cork Examiner (and widely reported elsewhere) he said:

‘I have been approached and asked to welcome the officers and crew, but in view of the insult given to the Catholic world on the death of the Pope, when the German Press termed our Holy Father a “political adventurer”, I cannot see my way to give any recognition, whether in my public or private capacity, to representatives of the German Navy.

I hope and feel that I am interpreting aright the views of the citizens of Cork in taking this action. This is my protest against the official German view, and not against the masses of the German people, who, I am sure, would be slow to offer such an insult to the Catholic world.’

BUT WELCOMED IN COBH

Hickey found a ready ally in the formidable Catholic bishop of Cork, Dr Daniel Cohalan, known affectionately as ‘Danny Boy’, who publicly congratulated the lord mayor on his stance. Nevertheless, despite the city’s blatant snub of the Germans, the Cobh and Irish Army authorities felt that they had little option but to extend the normal civic courtesies to the ship’s company. The following morning, Sunday, almost 200 Germans paraded to Mass in St Colman’s Cathedral, Cobh, and on the way back enthralled the people of the town with their rendition of stirring marching songs. That afternoon the ship was open to visits from the public, and again on the following Wednesday. Bus trips were organised for some of the ship’s company to the beauty spots of West Cork and Kerry, where they stayed overnight, while others got the train to Cork city or explored the harbour town. The weather gods, however, did not smile benignly on them; their visit was marred by incessant rain, resulting in the cancellation of several sporting events. Captain Lindenau recalled that on his previous visit to the town (in 1912), as a young cadet, he had witnessed a hurling match to which they had been invited by GAA official and nationalist activist J.J. Walsh (later to become the first postmaster-general in the Irish Free State).

Promptly at noon on Friday 4 March the Schlesien weighed anchor and began her voyage home to Wilhelmshaven, the chief naval base on Germany’s North Sea coast, after an absence of four and a half months. The ship was taken out of the harbour by the pilot, who left her three miles south of Roche’s Point. Earlier, Captain Lindenau spoke warmly of the hospitality they had been shown by the Irish people and expressed the wish to return someday.

MESSAGES OF SUPPORT

Lord Mayor Hickey was inundated with phone calls, telegrams and letters congratulating him on his stance, many of them from the UK. The German press, however, were indignant, with no intention of allowing this slight to the Fatherland to pass without comment. One Corkonian returning from Berlin recalled reading a newspaper that assured its readers that the lord mayor’s real name was ‘Icki’, not Hickey, and that he was really a Polish Jew; no self-respecting Irishman, traditional enemies of Britain, would have carried on like he did. The incident would not be forgotten, the paper asserted, and the day of reckoning for ‘Icki’ would come sooner rather than later.

It is not recorded whether Jim Hickey was unduly worried about falling into bad odour with the Nazi hierarchy. He went on to have a successful political career. He served as lord mayor of Cork on four occasions and was elected to the Dáil several times, the last at the 1951 general election. In 1954 he was nominated to the Seanad by Taoiseach John A. Costello. He passed away in 1966, at the age of 80, and was laid to rest in Rahan Cemetery near Mallow, Co. Cork.

The Schlesien, which took part in the opening salvoes of the war, remained in a secondary role throughout owing to her vintage (she was commissioned in 1908). On 3 May 1945, as she steamed to Swinemunde to evacuate 1,000 wounded soldiers, she struck a mine. She beached in shallow water, much of her superstructure, including her main guns, still visible. At the cessation of hostilities she was broken up, though some parts of the ship could still be seen as late as 1970.

Pat Poland is an Associate Fellow of the Royal Historical Society.

Further reading

Cork Examiner/Evening Echo, 27 February–2 March 1939.

Generalstab des Heeres, Militärgeographische Angaben über Irland [General Staff of the Army, ‘Military geographical information on Ireland’] (Berlin, 1940).

E. Kirwan, The threshold of a newer movement: the Cork Labour Party 1914–1950 (Cork, 2021).