RTÉ1, 12 August 2024

By Brian Trench

As you approach Valentia Island on the ferry from Renard Point, you see a village like very few others along the western seaboard. Knightstown displays a row of imposing buildings, none of them associated with church or state. The hotel grew in the mid-nineteenth century on the success of the slate quarry, and the larger buildings to its south were built a few decades later to accommodate the telegraph station and some of its 200 employees.

Valentia Island became a transatlantic hub in the 1860s, when, after a decade of trying, a cable was laid between the island and Newfoundland in Canada which could transmit the dots and dashes of the newly developed Morse code between Europe and North America.

The story of the cable’s laying, starting in the 1850s, is well known in the history of technology, and the story of the telegraph operation at Valentia is well known as part of the heritage of County Kerry. This documentary will help raise the visibility of these stories in the history of the country—and none too soon. Science and technology hardly feature in the national story. In an extended ‘decade of centenaries’, the decision in 1925 to commission the Ardnacrusha hydroelectric works deserves its place. An alternative History of Ireland in 100 objects could include a scientific instrument made by Grubbs of Dublin, a piece of the Leviathan telescope erected at Birr Castle and a piece of the first transatlantic telegraph cable that came ashore at Valentia Island.

It took a remarkable confluence of ideas and personalities to make this happen: an entrepreneur willing to pursue a speculative venture, investors willing to back him, an ‘improving’ landowner supporting business on his property, the commercialisation of gutta-percha in which to wrap the copper cable, physicist William Thomson’s realisation that a low-voltage signal boosted at the receiving end was better than a high-voltage signal which burned the copper wires, the daring engineering of Isambard Kingdom Brunel that made the 693ft paddle and propeller steamer Great Eastern possible, and the mariner skills that gave new use to this passenger ship.

The story is told with the help of maps, striking cartoon animations, many moody seascapes, dramatic re-enactments, interviews and footage from Heart’s Content, Newfoundland, as well as from Valentia, and images of bustling contemporary city streets with people on their phones. The key element is a long list of ‘talking heads’, mostly identified by nothing more than names and institutions. Cultural and literary historian Chris Morash of Trinity College, Dublin, is the most extensively used, though without reference to his recent writing on early telegraph cables or his Canadian origins. He is given wide scope to set the cable-laying in wider cultural contexts, but also to set the excited tone of the story-telling: this was the moon shot of its time, he says; this is where globalisation starts.

The documentary takes us eventually to robotic surgery and worldwide telecommunications, whose origins are traced back to this cable. But there are very many large steps in radio, visual media, silicon chips, software engineering, laser physics and much else between the Valentia cable and the systems that facilitate our current communications. The overworked analogies are drawn in part from the (very British) notion of The Victorian Internet, a book of 25 years ago on the telegraph written by journalist Tom Standage, who is extensively used here. The ‘annihilation of time and space’ claimed for the transatlantic telegraph in its own time is echoed by references to the global superhighway and the collapse of time and space in our own time.

The idea of a nineteenth-century technology changing the world, as presented in the documentary’s title (and in that of a 2003 book on the same topic), is amplified repeatedly through observations from more of the experts interviewed. As far as I can ascertain, only one of these is a historian of technology, Prof. Simone Müller, author of Wiring the world: the social and cultural creation of global telegraph networks (2016). The credentials of other experts are less clear and, in any case, not stated.

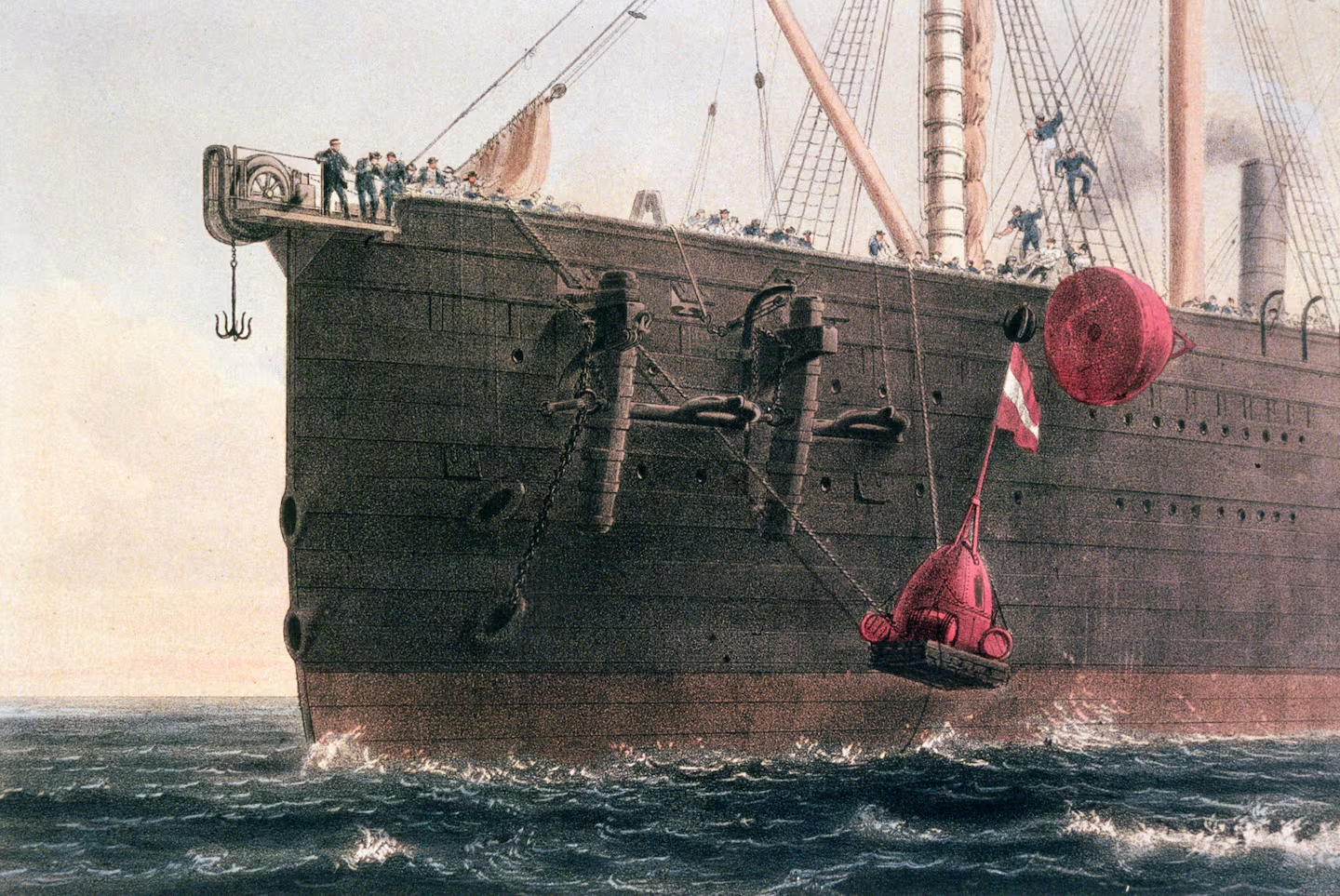

The story of the project is strong enough without so much dressing up. Following the laying in 1851 of a cable across the shorter span and shallower waters between England and France, the ambition to connect the Old World and the New World took shape. We are 30 minutes into the documentary before we get to the first attempt in 1857, which soon ended when the cable broke. The same again in 1858 (twice). On the third attempt the cable broke three times but, somewhat miraculously, it was lifted again from the seabed.

The connection made in 1858 was widely and wildly celebrated, but the cable stopped working owing to overheating. The project was denounced as a hoax and scandal and the experts were called to a public inquiry. Belfast-born physicist William Thomson was charged with finding solutions. Following the interruption of the American Civil War, the work resumed, using the Great Eastern. This leviathan had been launched in 1858 and was two to three times longer than the battleships used previously. Not only did this ship lay a cable end to end in 1866 but also later that year it retrieved a broken cable which it had lost and marked in 1865, and so a double connection was made.

Here an opportunity was missed to mark a significant Irish connection: the master of the steamer was Robert Halpin from Wicklow. He went on to become ‘Mr Cable’, leading the laying of tens of thousands of kilometres of submarine cable across the world. Halpin is commemorated in several places in Wicklow.

The documentary shows its concern for an international audience with brief notes on Irish history before and after the cable-laying. Its concern for a popular audience is reflected in the hype of the contemporary significance of the project. The repetition makes for a long 80 minutes, but the power of the story is immense and this telling leaves many lasting impressions.

Brian Trench was a senior lecturer in the School of Communications, Dublin City University.