ARNOLD HORNER

Wordwell

€55

ISBN 9781913934712

REVIEWED BY

Thomas O’Loughlin

Thomas O’Loughlin is Emeritus Professor of Historical Theology at Nottingham University.

Every map depends on a seemingly simple but necessary assumption: that it pictures reality—that is to say, that in a visual image we, who are viewing it, are seeing reality through it. It is easy to exemplify this: the distance between two dots, A and B, on the page can tell us accurately how much time/fuel we need to drive between two towns, A and B. So important is this notion that maps ‘picture reality’ (emphasis on the link to the extra-mental world) that we often find ourselves ‘ground-truthing’ maps and using this as a judgement of the map’s quality. This procedure, however, only has direct relevance to a fraction of the maps we see, those which are products of topographic survey and are designed to give us specific kinds of information such as distances and acreages. But we all know that a map—any map—is an editing of the information and is presented with particular focus from a definite perspective: it is one way of picturing reality (with the emphasis on the mind that guided the picturing hand). A map, therefore, is not simply an adjunct to historical research (e.g. giving information about how many houses were in a townland at a certain date) but is a primary historical source: it tells us about how a specific group of people, the mapmakers, understood and imagined the reality of the land and people addressed by the map. We not only use old maps in research but also decode them as historical witnesses in their own right, offering the historian a unique range of information.

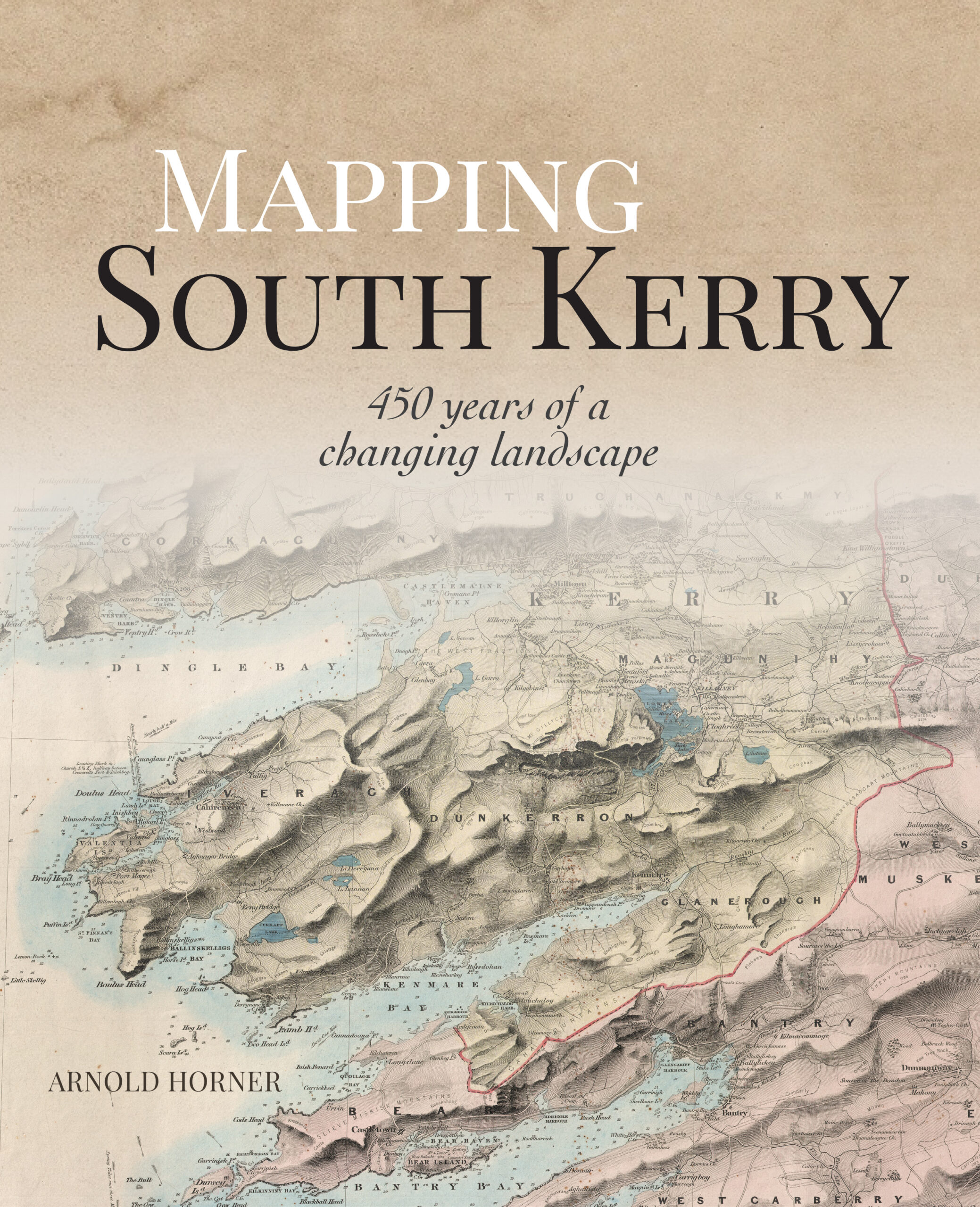

The reader might wonder why I have bothered to make this point about the epistemology of maps, but without noting it this very large (268mm x 215mm) and lavishly produced book might seem of value only to those who are interested in south Kerry or else in the history of cartography, viewing successive maps over a period as witnessing the technical evolution of cartography. But while this book does provide all the technical information that a historian of cartography seeks (see Part B, pp 305–41, and Part C, pp 344–420), it is also a model of how a longitudinal comparison of maps of a well-defined area can produce a historical narrative of a place and its people. This narrative is not just about the ground—the landscape—but also offers a unique contribution to the whole history of the place. If you have never considered this fuller dimension of maps as sources, this book will be an eye-opener.

That, however, does not mean that it is an easy read; Horner draws the reader into the whole development of mapping, from estate mapping (with even a nod to Ptolemy before that, p. 21) to the new mathematical world of the Ordnance Survey, beginning in the nineteenth century, and onwards to modern satellite mapping—while not forgetting the complex role of tourist mapping in a region that includes Killarney. This is complex in that even the Survey got involved in producing tourism-driven maps for the area around Killarney with a layer-coloured map, with the mountain landscape imaginatively portrayed—a practice still widely followed by the mapping agencies.

So how should one approach this book? Let me offer a suggestion. After reading some necessary background on the region (i.e. its baronies) and on mapping (pp xi–xiv), follow the changes in a few of the smaller towns in the later nineteenth century and early twentieth century. The section I would choose is that devoted to Killorglin, Cahirciveen and Kenmare (pp 208–12) as a demonstration of how those seemingly most detached of maps, those from the Survey, can, when read in conjunction with other local sources such as commercial directories, reveal the shifts in society in areas as diverse as the economy and religion. Then continue from p. 212 to p. 222 to see how valuation maps provide us with far more information than just the economy or the state of agriculture. In just these fourteen pages we are offered a master-class in how a historian can read and exploit a map for picturing not just the landscape but also the past. From this study—a smaller area and a shorter timespan—one can branch out to the rest of Part A (pp 1–304) of the book with a confidence that there is much more in maps than areas, heights and distances. That said, this book takes time to read. On virtually every page is the reproduction of part of the evidence (i.e. part of a map) on which the narrative is based (a rough reckoning gives six pages of text between p. 208 and p. 222, the rest being devoted to images), and one needs to devote as much, if not more, time to looking carefully at these maps as to reading the text. Horner doesn’t hide his evidence in a source footnote: he lays it out before our eyes.

Lastly, this book is beautifully produced in colour. Too often books on maps have too few maps, badly reproduced, too small to really study and without colour—none of these faults apply to this publication. This is a book that I imagine most historians will enjoy and will like to dip into as much as to read from cover to cover. Its title might put off those who do not think of themselves as specialists in matters relating to south Kerry, but they are missing a treat. Horner set a standard for cartographically based history in his Mapping Laois (2018), but I believe that he has surpassed himself in Mapping south Kerry. I am aware that there is not a word of criticism in this review, but one rarely encounters such a satisfying book.