By Cormac Moore

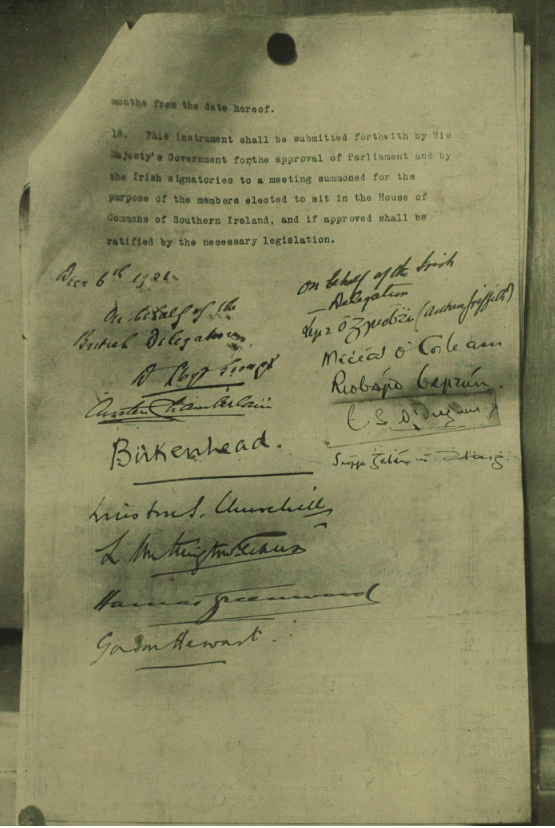

One hundred years ago, on 6 November 1924, the Irish Boundary Commission convened for the first time. It consisted of three commissioners: Eoin MacNeill, appointed by the Irish Free State government; Joseph R. Fisher, appointed as the Northern Ireland representative by the British government (the Northern Ireland government had refused to recognise the Boundary Commission); and the chairman, Justice Richard Feetham, a British-born South African-based judge who was also appointed by the British government. While the Boundary Commission ended a year later in great controversy, there was much controversy before it convened in the first place, almost three years after it had formed part of the Anglo-Irish Treaty between the British government and Sinn Féin plenipotentiaries in December 1921.

NORTHERN IRELAND OPTS OUT

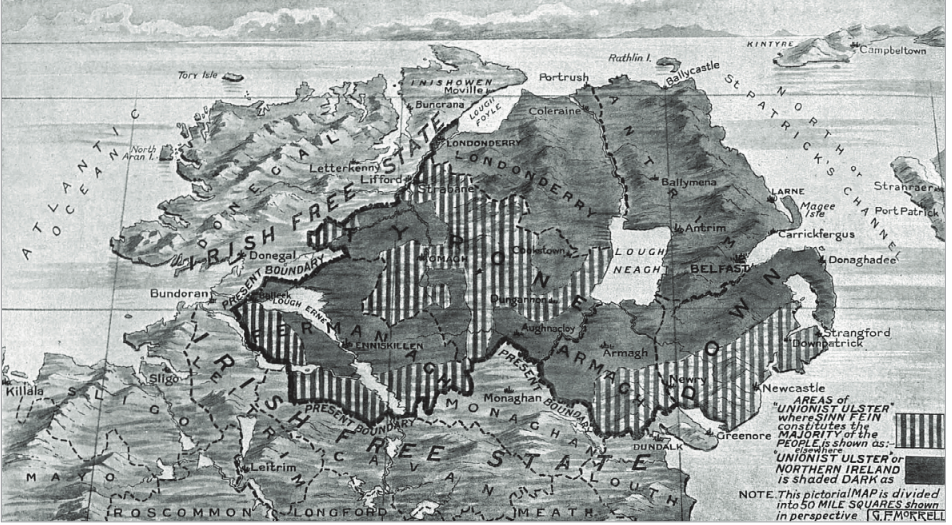

Under Article 12 of the Treaty, if Northern Ireland, which had been in existence since the summer of 1921, opted not to join the Irish Free State, as was its right under the Treaty, a Boundary Commission would determine the border ‘in accordance with the wishes of the inhabitants, so far as may be compatible with economic and geographic conditions’. Although Northern Ireland was nominally included in the Irish Free State, it took the first opportunity to opt out of the Dublin jurisdiction in December 1922, which then triggered the establishment of the Boundary Commission.

Even before the ink was dry on the Treaty signatures the interpretation of Article 12 was widely contested—not surprising, given its ambiguous wording. Most nationalists, both pro- and anti-Treaty, believed that the Boundary Commission would lead to the transfer of large swathes of territory from Northern Ireland to the Irish Free State, including counties Fermanagh and Tyrone, Derry City, most of south Down and south Armagh. The initial nationalist consensus over the Boundary Commission in large part explains why partition did not feature prominently in the Treaty debates of December 1921/January 1922.

What were the intentions of the British negotiators in relation to the Boundary Commission? Did they intend to rectify the existing border or to fundamentally change it and reduce Northern Ireland to an unviable size? While the British signatories claimed after the Treaty that it was always their intention to recommend a slight rectification, this is not the impression that they gave to the Sinn Féin negotiators. The British signatories were able to show flexibility on their interpretation of the Boundary Commission owing to the extremely ambiguous wording, something they consistently exploited up to the end of 1925.

‘THE ROOT OF ALL EVIL’

Ulster unionists were bitterly opposed to the prospect of a Boundary Commission, with the Northern Ireland Prime Minister James Craig describing it as ‘the root of all evil’. Although Ulster unionists were not party to the Treaty, they were now obliged to adhere to its clauses. The Boundary Commission reopened uncertainty and put Northern Ireland’s future, at least significant parts of it, in doubt yet again. Ulster unionists contended that they were promised by British statesmen that the Government of Ireland Act 1920 was the final settlement of the boundary question.

At a meeting of the Northern cabinet on 10 January 1922, the first since the Treaty was signed, Craig ‘thought the best course would be not to show our hand at the present time but to consider the matter very carefully during the few months that might elapse before the Boundary Commission would be established’. This was agreed upon and proved to be the correct and fortuitous decision from an Ulster unionist perspective, as a lot more time had elapsed by the time the commission finally met in late 1924.

Even though Craig claimed that the Boundary Commission was the ‘root of all evil’ for unionists, it resulted in uniting them and leaving the boundary unchanged. And Ulster unionists used the threat of the Boundary Commission to advantage in elections held up to late 1925.

For Northern nationalists, though, the Boundary Commission turned out to be the root of much evil. It gave false hopes for the transfer of large tracts of territory and people from Northern Ireland to the Irish Free State. The policy of ignoring and obstructing institutions of Northern Ireland was promoted and supported by senior Sinn Féin figures such as Michael Collins and Eoin MacNeill.

The Treaty resulted in differing opinions and strategies being adopted by nationalists within Northern Ireland. While nationalists living in the border regions, particularly in Fermanagh and Tyrone, were optimistic that they would be quickly transferred to the Free State, those living in Belfast and east Ulster knew that they would remain in Northern Ireland regardless of the generosity of the Boundary Commission. Unlike within Ulster unionism, there was a lack of consensus amongst Northern nationalists in general regarding the policy to be adopted towards partition and the Northern Ireland government.

The split within Sinn Féin over the Treaty compounded the confusion of Northern nationalists and effectively prevented the formulation of a policy that might have unanimous support. While local authorities such as Fermanagh County Council and some in south Down and south Armagh remained defiant and refused to recognise the Belfast parliament, others such as Tyrone County Council acknowledged the de facto jurisdiction of that parliament in view of what was described as ‘the temporary period during which the northern parliament is to function in this area’. The main argument put forward by local authorities who believed in recognising the Northern jurisdiction and by leading Sinn Féin figures like Arthur Griffith and W.T. Cosgrave was that they would lose nationalist control and would rob whole nationalist districts of effective representation in the face of the Boundary Commission.

The Northern Ireland government decided to act against the ‘recalcitrant’ local authorities. Over twenty nationalist-controlled authorities were suspended by April 1922. Paid commissioners were put in place to run the affairs of the suspended local authorities. On top of suspending local bodies, the Northern government looked to take back control of them. It did this by abolishing Proportional Representation (PR), compelling councillors to pledge an oath of allegiance to the Crown and the Belfast parliament, and by the rearranging of local government boundaries. Michael Collins, chairman of the provisional government from January 1922, complained to Winston Churchill that some of the decisions were made in anticipation of the Boundary Commission’s work, ‘to paint the Counties of Tyrone and Fermanagh with a deep Orange tint’. All these decisions that transformed the electoral landscape of Northern Ireland were evident when the Boundary Commission finally did meet in late 1924.

DELAY

The convening of the Boundary Commission was delayed by almost two years from the moment Northern Ireland opted out of the Irish Free State in December 1922. There were many reasons for the long delay. On the Free State side, the Civil War from June 1922 to May 1923 was the primary factor. Kevin O’Shiel, director of the North Eastern Boundary Bureau, established in October 1922 to prepare the Free State’s case, pointed out in January 1923: ‘What a ridiculous position we would cut—both nationally and universally—were we to argue our claim at the Commission for population and territory when at our backs in our jurisdiction is the perpetual racket of war, the flames of our burning railway stations and property and the never-failing daily lists of our murdered citizens’.

O’Shiel also argued that his bureau needed time to prepare their case. The dedicated team of staff of the boundary bureau did an enormous amount of preparatory and propaganda work by producing leaflets, pamphlets and a book, The handbook of the Ulster Question, as well as hiring legal agents in the north and advising Free State government ministers. O’Shiel argued that their motto should be Festina lente (‘make haste slowly’). Meanwhile, however, the Northern government was availing of the maxim ‘Delay defeats equity’ not only by changing the electoral structures of Northern Ireland but also by instigating infrastructure projects such as a reservoir in the Silent Valley in the Mourne Mountains to supply water to the residents of Belfast in 1923, and the reconstruction of Carlisle Bridge in Derry, all with a view to adding permanency to the six counties as a compact unit. The Free State was also guilty of ‘stereotyping the existing boundary’ by introducing customs barriers in April 1923 all along the land border between the Free State and Northern Ireland.

The Free State was also reluctant for the Boundary Commission to convene while the Conservatives were in power in Britain, although O’Shiel himself believed that it was best to deal with the boundary question while the Tories were in government, as they were ‘traditionally more straighter and honester’ (sic) in their dealings than the other parties. From the signing of the Treaty in December 1921 to the tripartite government London Agreement in December 1925 there were three general elections in the United Kingdom and four changes of government, another reason for the delay.

UNSTABLE LABOUR MINORITY GOVERNMENT

When the Free State government did get around to nominating its commissioner, Eoin MacNeill, in July 1923, it asked the British government (by then a Conservative administration led by Stanley Baldwin) to appoint the chairman and to constitute the Boundary Commission. The British Secretary of State for the Colonies, the Duke of Devonshire, suggested a conference instead, to be convened once a Free State election was held. Claiming that its main goal was Irish unity, much preferable to the unsatisfactory Boundary Commission, the Free State government readily agreed to a conference of the main protagonists. The conference was delayed by the Free State general election in August 1923, by the Imperial Conference in London the following month and then by a UK general election at the end of 1923. By the time W.T. Cosgrave met Craig in conference in February 1924 there was a new British government, the first Labour government, an unstable minority administration led by Ramsay MacDonald.

To show that it could govern, the last thing the Labour government wanted was for the Irish question to re-enter British party politics and engulf it in controversy again. However, during its short period in office throughout most of 1924, MacDonald’s government was faced with a significant constitutional problem owing to the Northern government’s refusal to appoint its representative to the Boundary Commission.

The February 1924 conference was adjourned with a proposal by the British government that both Irish legislatures meet to discuss issues such as railways and fisheries. It was rejected by the Free State government, though, as less than what was already available through the Council of Ireland, which existed on paper, and too temporary in nature. After another conference in April 1924 also ended in failure, under pressure from the Free State government the British government was forced to demand that Craig’s government appoint its representative. Craig, and many within Northern Ireland and Britain, believed that if the Northern government refused to nominate a commissioner the Boundary Commission could not convene at all. The wording of the Treaty explicitly stated that the Northern Ireland government had to appoint a commissioner, yet another draughtsmanship flaw of the Treaty.

Fearing that the non-convening of the Boundary Commission would be a breach of the Treaty by the British that would then see subsequent breaches by the Free State, particularly around the oath, the British government sought the advice of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council on what courses could be taken in consequence of the non-compliance of the Northern government.

Despite the enormous pressure put on MacDonald’s government by Craig and his die-hard supporters in British politics and the press, an agreement was reached between the British and Free State governments to pass simultaneous legislation to allow the British government to appoint the Northern Ireland commissioner.

By then, MacDonald’s government had appointed the chairman, Justice Richard Feetham, who accepted after the government’s first choice, former Canadian prime minister Robert Borden, had turned the offer down. While Feetham was based in South Africa, he was British-born and, according to his friend Lionel Curtis from the Colonial Office, ‘constitutionally of conservative temperament’.

By the end of October 1924, after legislation was passed in the Dáil and at Westminster, in one of its final acts the British Labour government appointed Joseph R. Fisher, a barrister and former editor of the Belfast unionist-leaning newspaper the Northern Whig, as the Northern Ireland representative on the Boundary Commission. Even though Edward Carson was mooted as the choice, Ulster unionists could not have selected a better representative, from their perspective, than Fisher.

When the Boundary Commission met for the first time in November 1924, it was unanimously agreed that ‘The Commission resolved that no statement should be made for publication as to the work or proceedings of the Commission except with the authority of the Commission’. It is clear that, while MacNeill held rigidly to this, Fisher was in constant communication with the wife of Ulster Unionist MP David Reid, providing updates on the Boundary Commission proceedings which were then filtered through Ulster unionist ranks. Much to the dismay of nationalists, Feetham, who had enquired about the feasibility of conducting a plebiscite beforehand, decided not to do so, and chose a quasi-judicial approach to the Boundary Commission. From December 1924 to July 1925, the three commissioners conducted informal and formal hearings, interviewing more than 500 witnesses based on written statements submitted in advance. While the Free State government and many nationalists from border areas fully engaged with the Commission, all were to be disappointed by the end of 1925, as the Boundary Commission collapsed in chaos and acrimony.

Cormac Moore is Dublin City Council’s Historian-in-Residence for the South-east Area.

Further reading

G.J. Hand, ‘MacNeill and the Boundary Commission’, in F.X. Martin & F.J. Byrne (eds), The scholarly revolutionary: Eoin MacNeill, 1867–1945, and the making of the new Ireland (Shannon, 1973).

K. Matthews, Fatal influence: the impact of Ireland on British politics, 1920–1925 (Dublin, 2004).

C. Moore, The Irish Boundary Commission: ‘the root of all evil’ (Kildare, early 2025).

P. Murray, The Irish Boundary Commission and its origins (Dublin, 2011).