By Michael Flavin

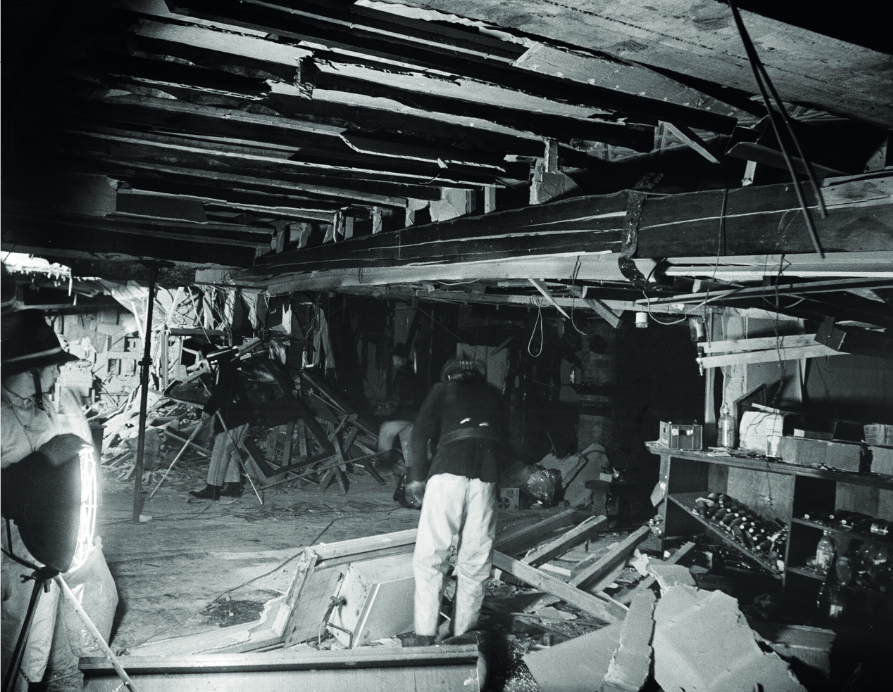

On Thursday 21 November 1974, a small IRA unit in Birmingham, acting without authorisation, planted bombs in two city-centre pubs, the Tavern in the Town in New Street and the Mulberry Bush in the Bull Ring. The Mulberry Bush was at the base of the Rotunda tower, a well-known Birmingham landmark, while the Tavern in the Town, a basement pub, sat underneath the New Street office of the Inland Revenue. A third bomb was placed at Barclay’s Bank on Hagley Road, one of Birmingham’s main arterial routes to the south of the city, but it failed to explode. The bombers intended to phone warnings through to the offices of the Birmingham Post, but the phone box identified for the purpose had been vandalised. By the time another phone box was found and the warning given, it was too late to evacuate, and the bombs exploded, killing 21 and injuring close to 200. Two of those killed were seventeen years old. Two were brothers, and Irish.

LARGE IRISH COMMUNITY

Birmingham had a large Irish community, many of whom had arrived in the 1950s, attracted by the National Health Service, by an education system that was free up to the age of eighteen and with the prospect of free higher education for those who got the grades, and by plentiful work opportunities. Irish construction workers built roads and housing estates, many of them working ‘on the lump’ (cash or cheque in hand without job security or compensation in the event of injury). Each morning, men lined up along the Coventry Road or outside the Mermaid pub in Sparkhill hoping for a day’s or a week’s work. Irish transport workers kept the local economy and society going. Irish nurses worked for the National Health Service. Irish parishioners swelled congregations at Catholic churches in Birmingham. The Irish immigrants added to the number of children on the register at Catholic schools. The Irish were economically, socially and culturally active, substantial contributors to the life of the city.

None of that mattered. As Birmingham awoke to devastation on 22 November, it was filled with fury against its Irish population. The Irish Centre, a cultural and social hub, was attacked, as were Catholic schools and churches. Irish workers were sent home, at risk of attack from their colleagues. People with Irish accents were refused service in shops. Traders in Birmingham’s Bull Ring market refused to handle Irish goods. An anti-Irish demonstration was held at the Longbridge car assembly plant, attended by 1,500 employees marching under the banner ‘Hang the bastards’. The Irish were the enemy.

BIRMINGHAM SIX

A few hours after the bombs went off, five Irishmen (four from Belfast and one from Derry) were detained at Heysham port. They were travelling back to Northern Ireland to visit family and to attend the funeral of James McDade, an IRA man who blew himself up on 14 November 1974 while planting a bomb at the telephone exchange in Greyfriars Lane, Coventry, c. twenty miles from Birmingham. Some of the men were carrying Mass cards for McDade. The five were transferred to Morecambe police station, where a forensic test established that two of the men had handled explosives—though the test was never repeated for confirmation purposes. Three of the five confessed under police interrogation. A sixth man, who had seen the five off at Birmingham’s New Street station, was arrested at his council house in Aston and also confessed. The police had their men.

Except they didn’t. The Birmingham Six were innocent. The test that produced positive results produced the same results from handling a range of substances, including playing cards (the five had played cards on the train journey from Birmingham to Heysham). In addition, the forensic scientist who undertook the tests on the Irishmen, Frank Skuse, was retired at the age of 51 early in 1985 by the Home Office on the grounds of ‘limited effectiveness’.

As for the confessions, they were the result of violence and maltreatment. The arrested men were assaulted by police and were later assaulted by prison officers. Their confessions contradicted each other and did not tally with the findings at the sites of the explosions themselves. For example, the confessions stated that the bombs had been carried in plastic bags, but examination showed that they had been in suitcases with ‘D’ handles. The locations of the bombs in the pubs, as recorded in the confession statements, were also incorrect. The contradictions in the statements did not matter, nor did the ‘Not guilty’ pleas of the Birmingham Six. They were sentenced to life in prison on the basis of what the judge, Mr Justice Bridge, later Baron Bridge of Harwich, called ‘the clearest and most overwhelming evidence I have ever heard’.

The campaign to overturn the miscarriage of justice was long, arduous and, for many years, fruitless. It was led by an investigative journalist, Chris Mullin, later Labour MP for Sunderland South. A first application to appeal in 1976 was refused, as was a full appeal in 1987. A second full appeal in 1991 was successful and the Six were finally released. Two of them—Richard McIlkenny and Hugh Callaghan—have since died.

KEEPING THEIR HEADS DOWN

The impact of the Birmingham pub bombings went far beyond the explosions. The Prevention of Terrorism Act was rushed through parliament in the bombings’ aftermath, allowing suspects to be detained without charge for up to seven days—a provision which has since been extended to 28 days. Furthermore, the Irish had held an annual St Patrick’s Day parade, a mark of the Birmingham Irish community’s self-worth and pride, since 1952, but the parade vanished after the bombings and did not return until 1996. That said, while the culture of the Birmingham Irish withdrew, it did not disappear altogether: Gaelic games continued to be played at Glebe Park, east of the city. The Irish Centre kept going, too. The Irish in Birmingham continued to sustain the economy and society; they just kept their heads down.

My semi-autobiographical novel, One small step, portrays what it was like to be a young Irish child growing up in Birmingham when, in the aftermath of the bombs, walking home in my Catholic school uniform was enough to earn me beatings. The novel’s hero, Danny Cronin, cannot understand the chaos around him and so retreats into a parallel fantasy world of rockets and aliens where his enemies disintegrate at the zap of a ray gun. Meanwhile, back in the real world, Danny’s parents’ marriage disintegrates too, and the streets of Birmingham get scarier and more dangerous. Furthermore, an unexpected visitor from Northern Ireland arrives at the Cronins’ home the morning after the bombings. Tension in the house builds to breaking-point. Danny, marginalised and isolated, distils his experiences into resentment and radicalism.

THE CAUSE OF ANTI-IRISH RACISM?

The condemnation of Birmingham’s Irish community after the pub bombings was absolute. It falsely conflated hard-working immigrants with a tiny number of perpetrators. It blamed the Irish as a whole for the strategy of the Provisional IRA, which had reasoned that bombs in Britain had far more impact than bombs in Northern Ireland. However, part of One small step’s contention is that the bombings did not cause anti-Irish racism because it was already embedded in British perceptions. As Edward Said, a Palestinian academic, notes in Culture and imperialism (1993):

‘Ireland was ceded by the Pope to Henry II of England in the 1150s; he himself came to Ireland in 1171. From that time on an amazingly persistent cultural attitude existed toward Ireland as a place whose inhabitants were a barbarian and degenerate race.’

Anti-Irish racism, latent in the ubiquitous anti-Irish jokes of the 1970s, burst to the surface when the bombs went off: it was not safe to be Irish in Birmingham.

WHO AND WHY?

The key question remains: who did bomb Birmingham and why? Paradoxically, the ‘why’ question may be easier to answer. The bombings were reactionary, a revenge attack for the death of James McDade in Coventry. As for who did the bombings, Chris Mullin, as part of his research, interviewed the actual bombers, which has made him a target of opprobrium for campaigners seeking justice for the victims in the years since. But if an investigative journalist knows who bombed Birmingham, it seems baffling, beyond credibility, that the police do not know too.

Mullin in the London Review of Books (2022) named two of the bombers, both of whom, Michael Murray and James Francis Gavin, are deceased. A third man, Michael Christopher Hayes, has admitted in interviews, available on YouTube, that he was part of the group who made and planted the bombs. The name of a fourth bomber is not in the public domain. Chris Mullin knows—which is probably why a prominent member of the ‘Justice for the 21’ campaign group shouted ‘Scum’ at him at an inquest in 2019—but the police surely know the name too. The same 2019 inquest also featured a witness known as ‘O’, who named Seamus McLoughlin, an IRA volunteer who died in 2014, as belonging to the planning team for the bombings (McLoughlin was OC of the Birmingham IRA). The police’s prosecution of six innocent men contributed substantially to the failure to apprehend the actual perpetrators.

The atrocious crime remains unresolved. Chris Mullin continues to be excoriated in some quarters despite having exposed a major miscarriage of justice. Anti-Irish racism in Britain carried on unabated into the 1980s and continued to find an audience. When Sir John Junor, editor of the Sunday Express, wrote, following the IRA Brighton bomb of 1984 which targeted the Conservative Party annual conference, ‘Wouldn’t you rather admit to being a pig than to being Irish?’, he was voicing a despairingly common view. Dangerous stereotypes about the Irish persisted, though they became less voluble after the Celtic Tiger made its appearance, signifying an increasingly self-confident, modern European nation. The Peace Process gained momentum, leading to the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, and Ireland strode into its post-conflict phase in which its broader constitutional status has once more become an object of discussion, with the distinct possibility of Sinn Féin in government north and south. Fora such as the Ireland’s Future events (irelandsfuture.com) create the opportunity to discuss what a post-partition Ireland might look like.

COMMEMORATION

A memorial in Colmore Row in Birmingham city centre records the names of the victims at the Tavern in the Town and the Mulberry Bush. Furthermore, an additional memorial, commissioned by the Birmingham Irish Association, was unveiled in 2018; comprising three steel trees, it stands outside New Street station. However, the impact of the bombings spread through the city and beyond, producing an indiscriminate wave of anti-Irish fury expressed through practices, images and tropes embedded in the colonial relationship between the two islands. Memorials are poignant and valuable and prevent society from losing sight of the suffering of others, and so there may one day be a memorial, too, for the Birmingham Six, the Guildford Four (wrongly convicted of two pub bombings in Guildford), the Maguire Seven (wrongly convicted of making the bombs for Guildford), Judith Ward (wrongly convicted of a coach bombing targeting British armed forces) and the other victims of British policing, British courts and the inflammatory rhetoric of a swathe of the British media.

Michael Flavin is Reader in Global Education at King’s College London.

Further reading

- Flavin, One small step (Aberdeen, 2022).

- Mullin, Error of judgement (Dublin, 1987).

- Mullin, ‘In court, again’, London Review of Books 44 (7) (2022).

- Said, Culture and imperialism (London, 1993).