By Damian Murphy

The Tipperary-born Father Theobald Mathew (1790–1856) established the Knights of Father Mathew, a Catholic temperance society, in 1838. Such was the interest in his cause—three million had taken the pledge by the mid-1840s—and such was its impact on society, particularly in the reduction in crime, that he was celebrated in his day and for some time afterwards. Dublin’s Whitworth Bridge (1816–18) was renamed in his honour as late as 1938. Mathew travelled abroad to promote the benefits of abstinence, and it was his visit to London in 1843 that prompted the first monument in his honour, a ‘testimonial’, on the outskirts of his adopted Cork.

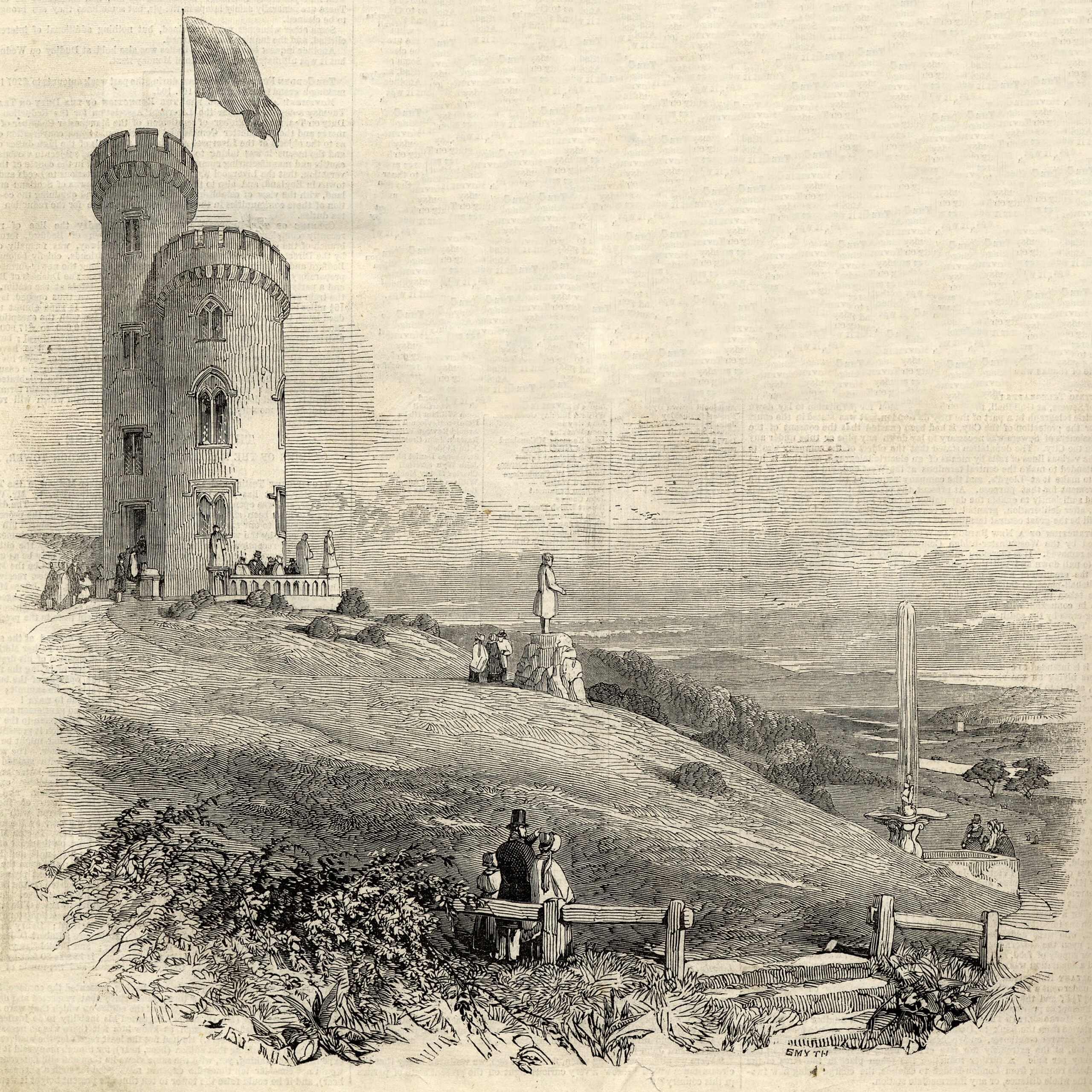

The testimonial, erected ‘at the sole expense’ of William O’Connor (d. 1849) in the grounds of his home, Mount Patrick, is composed of two cylinders with a slender stair turret-cum-flagstaff giving access to the three chambers stacked in the main tower. The theme is Gothic, and each tier is lit by distinct bipartite openings—square on the lowest tier, pointed on the piano nobile and Tudor on the uppermost tier—all given hood-moulded block-and-start casings and all originally partly filled with stained glass.

The interior continued the Gothic theme and, in addition to a biscuit-coloured chimney-piece carrying ‘a small basso-relievo figure of Father Mathew holding Britannia and Erin by either hand’, the compartmented ceiling of the saloon sat on a cusped frieze and centred on a foiled pendent rose. The chimney-piece was one of several reliefs and sculptures depicting Mathew; while most of those are long lost, the largest, a life-sized statue in early cast concrete, still stands on its podium surrounded by hydrangea in the shadow of the tower.

The tower and turret are finished with battlemented coronets of finely chiselled silver-grey limestone on ogee corbels, and the resulting silhouette is similar to Blackrock Castle (1828–9) on the opposite bank of the River Lee. Both were mentioned in the same breath by the American-born Asenath Nicholson (1792–1855) in her Annals of the Famine in Ireland (1851), leading some to mistakenly attribute the former to the same architects as the latter, the Pain brothers of Limerick. The true identity of the architect of the testimonial is found in a report in the Illustrated London News (18 November 1843), where, describing the laying of the foundation stone in the presence of Mathew, it says: ‘the stone having been lowered by pulleys over its bed … Mr Howard, the architect, from whose design the building is to be erected, led Captain Irwine … to the site [and] presented him with a massive silver trowel’. ‘Mr Howard’ was the Cork-based Robert Howard (1803/5–51).

The temperance movement petered out in Ireland in the late twentieth century and, while there are still some who ‘take the pledge’, abstinence today is most keenly observed in a health-conscious, secular context by devotees of Dry January. The Father Mathew Testimonial mirrored this decline and, occupied by caretakers until 1962, it was afterwards the target of vandals, who destroyed much of its external fabric and interior features. Happily, it was rehabilitated in the early 1990s and reworked as the vertical wing of a modern house. Its battlements remain a picturesque landmark rising above treetops on the road leading in and out of Cork by the Dunkettle Roundabout.

Damian Murphy is Architectural Heritage Officer, NIAH. Series based on the NIAH’s ‘building of the month’, www.buildingsofireland.com.