By Niamh Brennan

In 1825 the Commissioners for Irish Education recommended the establishment of a national school system in Ireland. This was agreed upon and implemented by the British administration in Ireland by 1831. The British government’s main overall objective was to establish tighter control of the Irish population, and to reduce the influence of hedge schools and religious schools in Ireland. The national school inspectorate was established in 1832. Under the new education system, teachers and inspectors were appointed.

Inspectors have been described as ‘system builders as well as monitors of school quality’. A number of district inspectors’ books and organisers’ observation books from a variety of national schools have been deposited with Donegal County Archives.

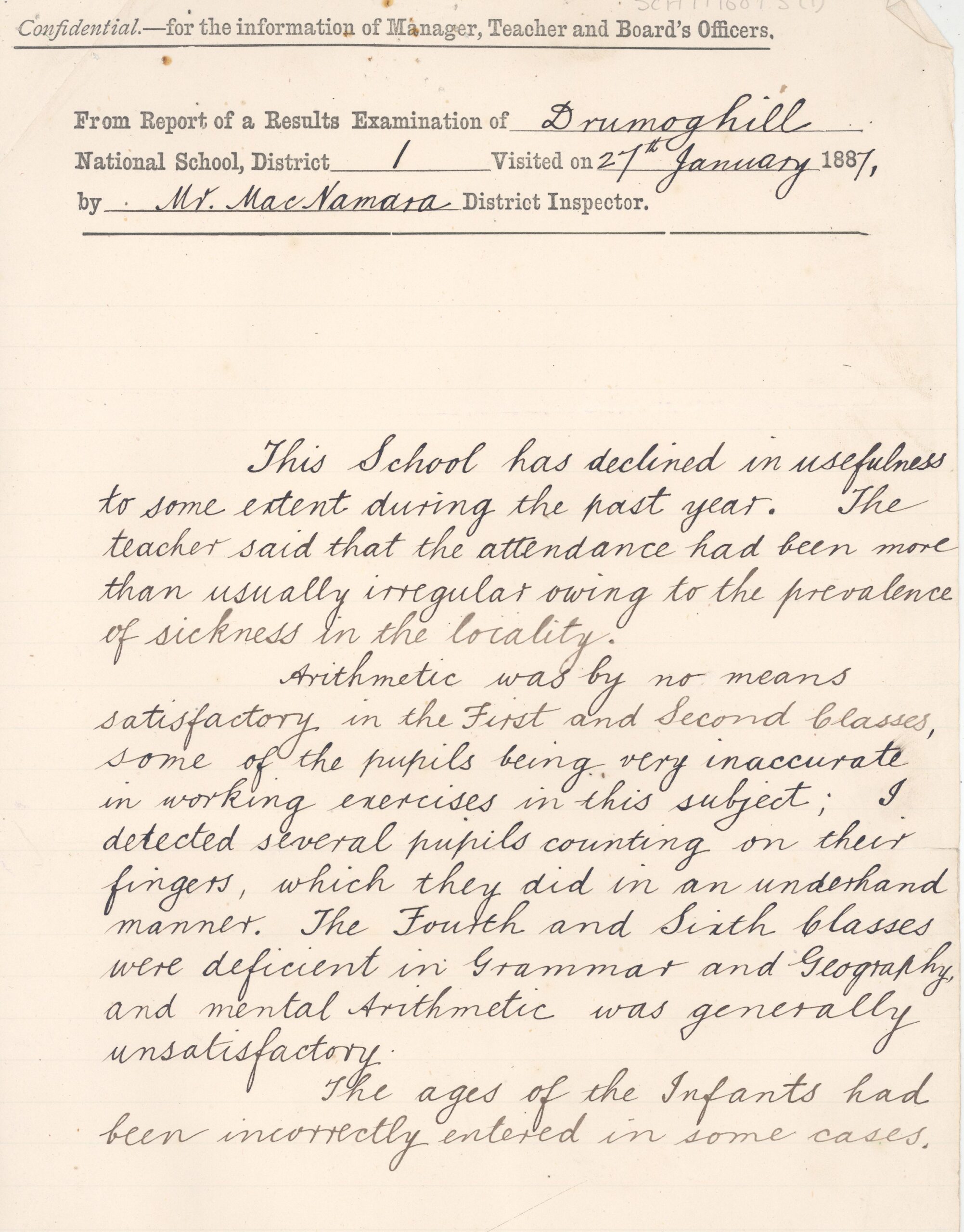

The earliest of these report books date from the mid-1850s. Some reports give us a unique glimpse into the lives of children and teachers in villages and townlands, in small and often remote rural communities and schools in post-Famine Donegal. A district inspectors’ observation book for Drumoghill National School (1882–1931) includes the names and appointment dates of teachers and school monitors and many observations on children’s progress over the decades. Inspectors’ written comments tended to be openly critical and unfiltered, and this report book includes a harsh comment about a teacher who was clearly working under serious difficulties. Apart from irregular attendance (often owing to ‘sickness in the locality’) and difficulties in maintaining discipline, the school’s accommodation was particularly poor. In July 1886 the inspector admitted that, when these disadvantages were taken into account, there was ‘evidence of a good deal of hard and patient work on the part of the teachers’, though he felt that certain subjects were neglected, including ‘explanation, notation and phrase spelling’.

Comments on unsuitable accommodation feature in most nineteenth-century school reports. Reports from Dooey National School in Lettermacaward commenced in 1877 with a comment on each class’s educational standards but also on the inadequate size of the school building and a recommendation that a larger house be built for the school. According to Dúchas, a thatched cottage was used for the school in Dooey. Concern about the spread of contagious disease was sometimes evident, with advice about ventilation of rooms in Dungloe National School given by the inspector in November 1912.

The Dungloe National School district inspector’s report book dates from 1856 to 1912, spanning a huge period of societal change and development. Criticisms about the unsuitable condition of the building are similar to other reports, yet the inspector was consistently complimentary about both the children’s progress (‘read and spell well and know the outlines of the map of the world’, 28 August 1858) and the mode of teaching (‘very creditable and evident of careful and zealous teaching’, 19 July 1858). Detailed critiques of children’s abilities in arithmetic, geography, spelling and writing continued as the decades passed. On 5 July 1859 the inspector noted that ‘all read the selections from the British poets once a week, proficiency in all subjects is excellent’. Such comments give us glimpses into the nature of the curriculum at that time in Ireland. On 11 July 1912, an inspector suggested that the subject of history might encompass ‘more than stories of the O’Donnells’. This tells us that Irish history was being taught at some schools at least by then, even if it was not always the history approved by the Commissioners of Education.

The dearth of adequate supplies of educational materials, which is marked at every single visit in Dungloe, was usually mitigated by comments that ‘a sale of work is about to take place’. There was never any referral to State funding for necessary books or equipment. Older pupils, with no access to second-level education, sometimes stayed on in national schools as ‘monitors’ or teaching assistants and were doubtless helpful in schools with ever-increasing numbers of students and few staff. However, doubts about the abilities of class monitors or older students to supervise younger children were expressed by the Dungloe inspector in September 1900: ‘too many monitors were being employed and … one third class boy was being instructed by another while the others were acting as monitors’. As decades passed, the primary school curriculum gradually widened. Dungloe National School’s subjects by the early twentieth century included gardening, composition, Irish (an ‘extra subject’ prior to independence) and ‘singing in harmony’, with reports given on these lessons.

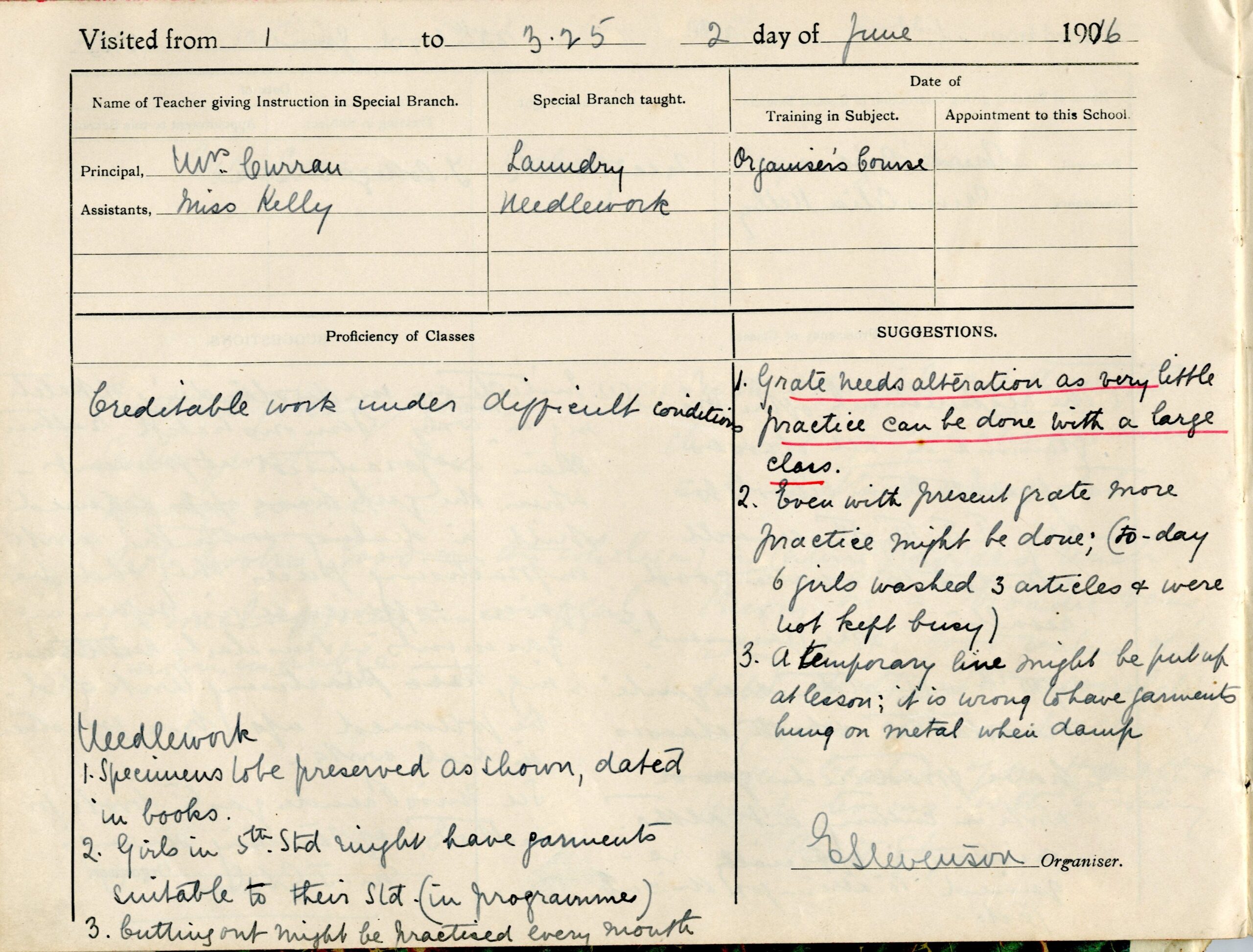

As well as district inspectors’ reports, where inspectors wrote reports on teaching and the condition of the school, organisers’ observation books survive in the Archives. The latter reports were written up by teachers or external experts in certain subjects. An organiser’s observation book for Ballymore National School in Dunfanaghy reviewed the progress of students and teachers at specific subjects and classes. For girls these included needlework, cookery and laundry.

Visits sometimes included lectures and demonstrations by the visitor, who would then make recommendations in the report books. Referring in particular to teachers’ attempts to pass on cooking skills, the inspectors could be critical of the lack of proper equipment in the classroom, often recommending that they purchase stoves or tables. Of course, teachers could not afford these and no government funding seems to have been forthcoming, as the evidence shows the complaints about equipment continuing in the decades that followed.

The organiser’s reports following a visit to Ballymore National School recommended that the girls sew aprons and tea towels (flour bags could be utilised) as preparation for introduction to the subject of cookery (August 1911). On 7 June 1916 the organiser suggested that practical dishes be made from vegetables grown at home, mentioning potatoes, leeks, onions, cabbage and turnips; recipes referred to included oatcakes, savoury oatmeal pudding, stewed potatoes and onions and herring dinners.

It was not only practical skills that the children were taught and observed on; the organiser noted on 2 August 1935 that the assistant inspector of music had criticised the materials in the school as too poor to work with and that ‘only eight children show any musical prowess with not one singer in the whole school’. Harsh criticism indeed!

The inspectors’ reports reflect social and economic life in rural Ireland in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They also document the dedication of the inspectors who strove to improve children’s education and teachers’ skills and to increase the overall standard of primary school education in the country.

Niamh Brennan is Archivist with Donegal County Archive.