TG4 and BBC2 NI, 9 and 13 October 2024

By Sylvie Kleinman

‘Did you never hear tell of the skulls they have in the city of Dublin, ranged out like blue jugs in a cabin of Connaught?’ A character in Synge’s Playboy of the Western World (1907) had supposedly seen them in Trinity College, Dublin. But they were there. The quip is used to scholarly advantage by Dr Ciaran Walsh (Anthropology, Maynooth) in summarising how he teamed up with Marie Coyne, a native of Inishbofin, Co. Galway, and founder of the island’s Heritage Museum, to have them returned. This is one of two major explorations in Iarsmaí of how Irish institutions are ‘wrestling with the decolonisation’ of collections ‘acquired during the British colonial period’, as per the promotional wording.

Public history and heritage are addressing how they appear to be perpetuating hegemonic discourses. Irish museums are transforming how the public, curators and staff experience visualising objects and artefacts acquired in the past when colonialist, racist and exclusionary mind-sets prevailed. Ireland is now tackling cultural decolonisation, a catch-all concept which here also encompasses outdated representations of who made whose history (which countries without a colonial past also started addressing).

Unsurprisingly, Iarsmaí opens with iconic footage of toppling Coulson into Bristol harbour, Black Lives Matter and Rhodes Must Fall protests, and here students decrying the now de-named Berkeley Library in TCD. The Ulster Museum’s (UM) Head of Curatorial, Hannah Crowdy, walked us through the cases and displayed an Australian Aboriginal shield. The UM is re-evaluating its World Cultures collection with the public, researching how certain objects entered collections, e.g. through gifting, and tracking their actual provenance. The latter process is vital if restitution to descendant communities has been requested, and it is often complex bureaucracy and conditions of preservation in countries of origin that delay processes, not willingness to restitute.

Uncomfortable truths and complex global stories are now exposed but renew perspectives: ‘curation is an act of storytelling’. A compelling dimension of the film was following the Nigerian-born Irish broadcaster and Gaeilgeoir Ola Majekodunmi on her journey to Oxford, Nigeria and the storage rooms of the National Museum of Ireland, Collins Barracks. There she admired some fine Benin bronzes and discussed them with Aoife O’Brien, curator of the ethnographic collection, who also foregrounded provenance. Majekodunmi went to Nigeria to explore the eventual return of the bronze and brass sculptures but also to discover the technique of crafting them, as it is still practised today by specialist artisans. These fine Nigerian artefacts were booty looted during a punitive British expedition in 1897, but viewers got no broader perspectives outside the Anglophone world. Museums in Germany had purchased some ‘British’ Benin bronzes, but a popular campaign took off for cultural restitution back in the 1970s, though admittedly it is only recently that action has been taken internationally. France, too, was scrambling in the same part of Africa in the late nineteenth century and has recently returned some of its Benin bronzes.

In a brief look at the colonialism embedded in Belfast’s street names, statues and civic art, Fearghal Mac Bhloscaighconsidered the legacy of Arthur Chichester’s ruthless scorched-earth tactics and mission to ‘entirely enslave the Irish’. This became the blueprint for conquest and colonialism elsewhere (might we note after the Iberian conquistadors). High on her pedestal, the ‘Famine’ Queen Victoria is now incongruous, as is the idealised and hagiographical mural in City Hall portraying Chichester in the Founding of Belfast (John Luke, 1951). This raised vital questions about the layering of memory in public spaces and the perpetuation of conventional triumphalist ‘history from above’. Though gender, popular radicalism and revolution were never discussed (and their absence in history is not confined to the colonised), Iarsmaí aptly signalled at the very end the unveiling in Belfast on 8 March this year of the statues of Mary Ann McCracken and Winifred Carney.

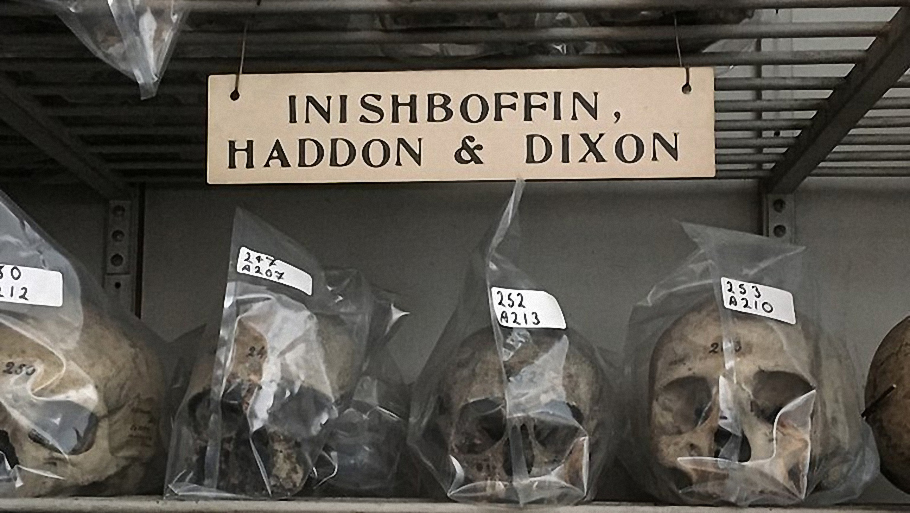

Closure for the people of Inishbofin seemed indisputable in the age we live in, and the film covers the protracted process leading to the eventual return of the skulls and their reburial on the island (July 2023). The scenery was awesome and we sensed the significance to locals of the sacred Christian ruins adjacent to their graveyard. But tensions and barely veiled cynicism about TCD’s ultimate decision were palpable during a prior consultation visit there by the college’s Legacies project team. This was filmed and made for some awkward viewing in an otherwise seamless and attractive visual production. Ciaran O’Neill (TCD) outlined how the crania were taken in 1890 for anthropometrical research without the permission of the local community by two Dublin academics, Alfred Cort Haddon (who knew Synge) and Andrew Francis Dixon. Evidence had survived: Haddon’s field diary and a photo of the niche in the ruins of St Colman’s monastery where he had helped himself. Walsh had seen the skulls, gifted to TCD in 1892, clearly labelled ‘Inishbofin: Haddon and Dixon’. He was instrumental in helping Coyne to progress the restitution campaign, started in 2012. But a global ethical paradigm shift had led, in 2009, to TCD returning Maori remains to the National Museum of New Zealand. Within cultures, human remains are also now regarded as just that. Paradoxically, restitution of the skulls was eased because the scientists had labelled them, and Iarsmaí filmed their dignified exit from TCD, return and emotive reburial on Inishbofin. A great-granddaughter of Haddon’s came to apologise on behalf of the family.

Iarsmaí showed a team measuring skulls in Inishbofin in 1893, and O’Neill briefly alluded to the ‘science’ of craniometry. But he had addressed this in Ardal O’Hanlon, Tomb Raider (reviewed in HI 30.6, Nov./Dec. 2022), which looked at the Harvard Expedition’s post-1922 quest for Irish racial characteristics. Would it not be historically accurate, and less insular, to relocate the theft of the Inishbofin crania within late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century global anthropometrics, and not pin this on British colonialism? Are there no dusty European skulls in European anatomical collections acquired for the same purposes, in similar circumstances? Iarsmaí was also screened publicly in Belfast and Dublin with Q&A sessions, and, despite driving some evidence to fit a specific agenda, is otherwise an impressive landmark production.

Sylvie Kleinman is Visiting Research Fellow, Department of History, Trinity College, Dublin.