NICHOLAS K. ROBINSON

Four Courts Press

€36

ISBN 9781801511353

Reviewed by

Sylvie Kleinman

In the late 1700s, élites in salons or smoking-rooms, or anyone gazing into the windows of bookshops and print-sellers in London or Dublin, consumed and experienced satirical cartoons. This was the golden age of English caricature, and increasingly elaborate and richly coloured visual satires graphically, and often quite wickedly, mediatised or mocked the posh, celebrities, politicians and sometimes ordinary people. One of the most instantly recognisable politicians by the 1820s was the iconic Irishman Daniel O’Connell. Though he only appears in three here, and cartooning styles changed in his times, we note with interest that two were issued in Dublin, as discussed below. In this splendid book, Nicholas K. Robinson explains briefly that, for the period considered, Dublin was the only city apart from London with a sizeable trade in satirical prints, but also a hub of piracy.

Here Robinson selects 105 prints, chronologically representing Irish people or themes during this pivotal era in the genre and showcasing the skills or audacity of a range of artists. The descriptive text is brief but displays Robinson’s enthusiastic eye for detail. As as Trinity College graduate in the late 1960s, he ‘avoided’ practising law by working as a cartoonist, his ‘Nick’ cartoons mostly published in the Irish Times. But he was also an avid and discriminating collector and in 1996 donated to Trinity College Library his treasure trove of 1,335 political and social caricatures with Irish themes dating from 1780 to 1891. All (as below) are freely available in Trinity’s Digital Collections to download and entertain, enlighten or infuriate (although permission is needed to reprint).

Successful political cartoons usually involve immediate recognition of people in context, and might depict or caricature an event or ephemeral public conversation that may elude us today. Robinson highlights how the Irish or Irish themes rarely inspired London’s thriving community of caricaturists until the 1780s. His scholarly interest led to his publishing Edmund Burke: a life in caricature (1996), an extensive discussion linking the genre to the social-mediatised representations of emerging characters as public opinion was intensifying. But this was equally an age when Anglo-Irish political and national identities were affirming themselves in unprecedented realignments. Rarely seen is the subtly mocking ***** [Burke] on the Sublime and Beautiful (1785), depicting him as the chief bore in parliament, a far cry from his august Victorian statue in front of Trinity. Burke appears in six prints, as does Henry Grattan, and Richard Brinsley Sheridan overtakes them.

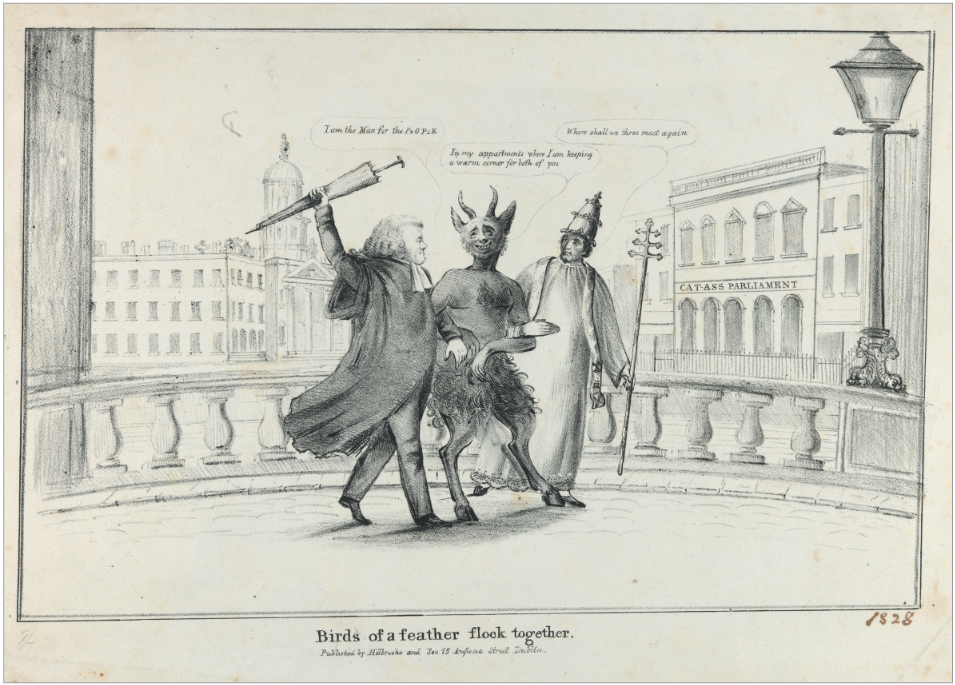

Unsurprisingly, royals, aristos and toffs also appear frequently and, of the very few women, Lady Caroline Lamb in A Curiosity of Ireland (1814) peers at the viewer, warming her bare legs by the fire. Wellington’s martial glory allied with his reputation as a ladies’ man placed him in highly suggestive scenes. In the saucy The Master of the Ordinance Exercising his Hobby (1819?), he sits astride an upwardly pointed canon as intrigued young ladies blush but watch with enthused titillation. We leave it to HI readers to discover the salacious speech bubbles. This is one example of Robinson seeking out the Irish version of a print (usually) originally published in London, and from the book’s index I have extracted four Dublin publishers. The endpapers showcase the engaging style of one of a handful of Irish artists, the young Richard Newton (Progress of an Irishman, 1792), whose talented life ended when he was only 21. To provide a balanced spread, Robinson judiciously only selected three of the innumerable cartoons featuring O’Connell. Another Irish cartoonist who prospered in London was John Doyle, or ‘H.B.’, who repeatedly lampooned O’Connell. Here we only see one of his prints, in which Thomas Moore’s reputation outweighs Walter Scott’s (and that he was the grandfather of Arthur Conan Doyle is not stated). A personal favourite since first discovering it in the National Library of Ireland is Birds of a Feather Flock Together (Dublin, 1828?), here reproduced for the first time. Uncoloured and relatively simple, this rare view of Dublin depicts Dan defiantly crossing the bridge (Carlisle) later renamed after him, entwined with the devil and the pope. We see a ‘Cat Ass Parliament’ (the Corn Exchange on Burgh Quay where O’Connellites gathered), and to the left the Custom House (with its original dome).

Major events like the 1798 Rebellion and the Union obviously inspired, and for the latter we see St Patrick astride a bull, doggedly chasing after Pitt and Fitzgibbon, who have abducted Hibernia after Carrying The Union (1800). Generally, ordinary people are rare, and before considering racialised stereotypes we should ask how the plain folk were depicted by English cartoonists. Probably the most denigrating is Irish bogtrotters (1812?): agile barefoot peasants trudge through a boggy Irish landscape carrying spuds, turf, buttermilk and a shillelagh. Despite their simianised faces, they appear spirited and industrious. Yet John Bull, ‘Poor’ Pat and Hibernia are often seen together looking humble and similar, enjoying a particular bond. We will not speculate on how accurate the technique of defending Ireland against a Napoleonic invasion would have been, but in The Scare Crows arrival, or Honest Pat giving them an Irish Welcome (1803) a stalwart (and well-shod) Paddy, ‘not to be blarney’d’, resolutely hurls a shovel of the old sod at ‘Master Bonny’.

This large coffee-table book is not a probing academic treatise, but it is a gateway to a vibrant topic. Its high-resolution images are sharply coloured, making it a pleasure to peruse.

Sylvie Kleinman is Visiting Research Fellow at the Department of History, Trinity College, Dublin.