BRIAN HUGHES

Four Courts Press

€22.45

ISBN 9781801511193

Reviewed by

Niall Quinn

Niall Quinn is a former international footballer with an MA in History from Dublin City University.

I’m 58. When I was in school, history was like a bowl of porridge slapped down at breakfast. It wasn’t meant to be nice; it was good for you. So we half-digested a litany of names and dates and we coughed them up again as best we could at exam time. Still, it was my favourite subject. What we were served was very heavy on the glory of 1916 and sketchy about events on either side of it. The class conflict of the Dublin Lockout got a quick glossing over until James Plunkett’s Strumpet City came on our telly. The venom of the Civil War years was considered too complicated for our delicate ears.

Basically, the old curriculum was a terrible way of telling a great story. Years later, I remembered something from my own history. In 1983 a promise was made to my teacher mother, a promise made by both myself and Arsenal Football Club. We swore blind that if she let me go off to London to try to become a professional footballer my education would not be neglected. Off I went and forgot all about the promise. Mid-Covid pandemic, I set about filling that gap in my life and making good on my promise. Of course I chose history, and guess what? Our way of telling our national story has changed utterly and for the better since my schooldays.

It turned out that the names that we slavishly attached to the dates actually had personalities of their own. They lived interesting lives on either side of 1916. I discovered Oscar Traynor. He played professional football for Belfast Celtic. That would have fascinated me as a kid. Joseph Mary Plunkett (nobody told us about Grace) enjoyed roller-skating in both Algiers and Earlsfort Terrace. James Connolly, over a century ahead of his time, toured America in 1903, advising people away from the two main political parties and their class bias. Connolly was born in Cowgate, Edinburgh, in 1868. He was baptised in the same church, St Patrick’s, Cowgate, in which his parents got married, the same church where Hibernian FC was founded in 1875.

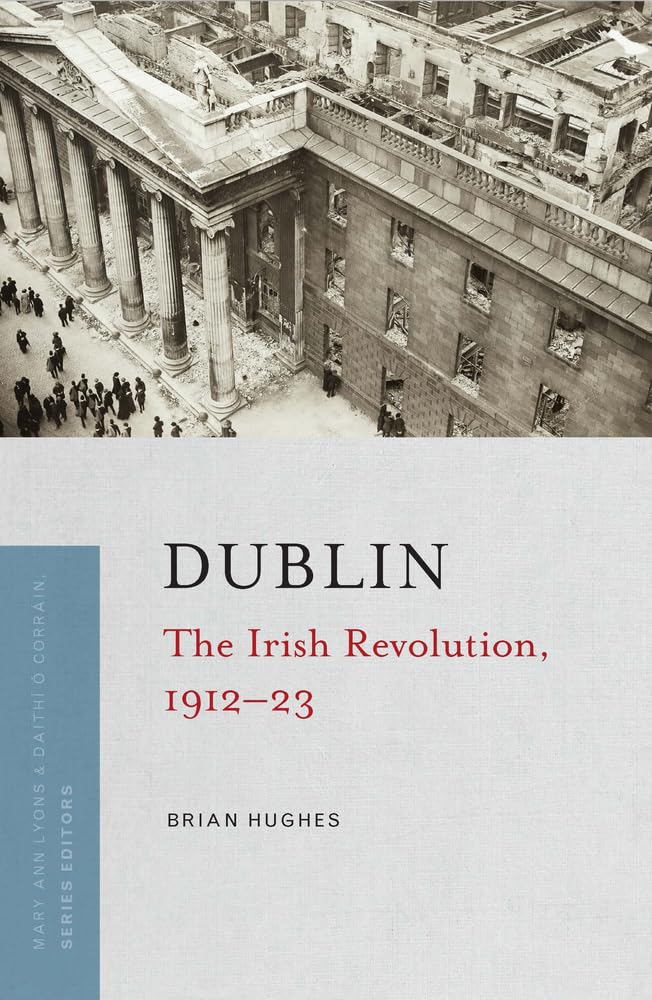

For over a decade now Four Courts Press has been producing a series of books that attempt to marry local history with our national story. Brian Hughes’s is the latest and probably the most ambitious. It is an impressive undertaking to place those great events onto our familiar streets.

The first of Ireland’s three Bloody Sundays, sparked by James Larkin’s speech on Sackville (O’Connell) Street on 31 August 1913, gets dealt with at quite a pace, for instance. Speaking outside Liberty Hall the previous Friday, Larkin made a careless accusation about a soccer match to be played the next day between Shelbourne and Bohemians: ‘There are scabs in one of the teams, and you will not be there except as pickets’. The next day violence erupted outside Shelbourne’s ground in Ringsend. Larkin was consequently banned from making a planned speech on the Sunday. That afternoon many of Larkin’s followers were at a rally in Croydon Park, Marino, but Larkin spent the morning being disguised with theatrical make-up and a fake beard by Constance Markievicz. Wearing the overcoat of Markievicz’s husband, Casimir, and disguised as a deaf old man (deaf because answering questions would reveal his Liverpool accent), he entered the Imperial Hotel, assisted by his ‘niece’, Nellie Gifford (older sister of Grace). The Imperial Hotel was owned by Larkin’s arch-enemy William Martin Murphy. Later, Oscar Traynor would command a republican battalion there, protecting the GPO across the street during the 1916 Rising. Larkin appeared at the balcony of the hotel’s smoking-room, tore off his beard and spoke briefly to the surprised crowds below on Sackville Street: ‘I am here today in accordance with my promise’. He vowed to ‘remain till I am arrested’. He had barely uttered those words when the police baton-charged; two were killed and up to 600 injured.

All the small details of this story are what make it interesting to me. The Imperial was over Clery’s department store (which William Martin Murphy also owned). It was gutted by fire during the 1916 Rising, with Traynor and his men having to make a last-minute run for it. Half a century later, Traynor had his political retirement dinner in Clery’s. William Martin Murphy, despite being a Corkonian, went to Belvedere College, just a couple of hundred yards up the road from his hotel. And so on …

These small details, the fabric of any local history but just footnotes to the national narrative, intrigue me. It is unfair, however, to focus on what this reader missed. There is so much for Hughes to get through in this attentively researched book that he can be forgiven for skipping colourful diversions.

The heart of the book are the chapters dealing with the period from Easter 1916 to the end of the Civil War. Hughes usefully surveys the demographics of the Dublin and Fingal brigades of the IRA, giving us a fuller picture of the involvement of ordinary Dubliners. Likewise, the attention to Dublin’s geography as a backdrop to guerrilla warfare and what Hughes describes as ‘the counter state’ are invaluable contributions. The story of Dublin and the Irish revolution is really a mosaic of thousands of smaller stories. Brian Hughes has done a truly impressive job in corralling so much into a single volume (the notes and bibliography alone take up 42 pages).