By Mark B. Roe

The records of the British and old Irish parliaments contain detailed evidence of one of Ireland’s earliest experiments in institutional child care: the Foundling Hospital. Annual admission figures are available for 82 out of the 100 years during which the hospital accepted admissions. From these we can calculate that approximately 127,000 children were admitted in total. Overall mortality figures, provided by the hospital itself, can also be found covering about 55% of all admissions. These reveal that for every 1,000 children taken in 800 died—probably over 100,000 in total. How did such a death toll arise, and why did it continue for so long?

The origins of the hospital date from 1730, when an enquiry by the Irish House of Lords revealed the ‘deplorable’ treatment of foundling children in the city of Dublin. At that time the Anglican Church parishes, which provided an early form of local government, were nominally responsible for the care and upbringing of these abandoned infants. The enquiry found, however, that Church functionaries, in order to avoid this expense, were secretly conveying infants discovered on their own patch to neighbouring parishes and abandoning them there. Upon discovery, the infants were often secretly conveyed to yet another parish—a deadly ‘pass the parcel’ which, it was found, led to the deaths of many children. The activity was apparently so prevalent that Dublin had even evolved its own terminology—that of ‘lifting’ and ‘dropping’—to describe it. Furthermore, it was found that during the process the infants were often given diacodium, a sweetened decoction of opium, to quieten their cries and prevent detection. Particularly singled out for criticism were the churchwarden and parish nurse of St John’s, a small parish of crowded courts and narrow lanes which sloped steeply down from Christchurch Cathedral to the Liffey, but it was apparent that the practice was carried on in many parishes. As long as eight years previously, William King, archbishop of Dublin, had written to his clergy condemning the practice, apparently to no avail.

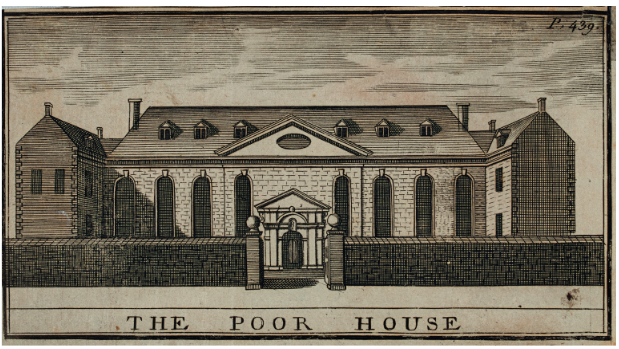

Shortly after the 1730 enquiry, an anonymous pamphlet was published in Dublin. The case of the foundlings of the city of Dublin gave further details of the practice and estimated that ‘thousands’ of infants had been ‘murdered’ in this way. It proposed a simple solution. Instead of individual parishes being responsible, the infants should all be sent ‘to one common house of reception’, where they could all be‘maintained by one common fund’. This would remove the financial motivation for their destruction. To avoid the ‘time and expense’ of constructing a new building, the anonymous pamphleteer suggested that the role could be adequately fulfilled by the existing workhouse on James’s Street.

Dublin’s iconic workhouse had been built between 1704 and 1706 to solve the problem of wandering beggars who were said to crowd the streets of the city, but by 1730 it was clear that it had failed in its original purpose and there was little opposition to adding an additional function—that of foundling hospital—to its role.

Within months legislation was enacted to support this new role. Archbishop Hugh Boulter, at the time the most senior figure in the government of Ireland, was central to the new development and personally instructed that a turntable,allowing the anonymous deposition of infants, be installed at the gates. That same year Boulter had written (although not referring to the Foundling Hospital) that ‘the great number of papists in this kingdom, and the obstinacy with which they cling to their own religion, occasions our trying what may be done with their children to bring them over to our Church’. Proselytising was to be a central feature of the Foundling Hospital throughout its history.

From the beginning the workhouse struggled to fulfil its new role. The first year of operations saw the new ‘Foundling side’ take in 263 abandoned children. (Adults continued to be admitted to the ‘Workhouse side’.) Numbers increased rapidly, so that by the third year the annual intake had risen to 533 foundlings. But how to care for such fragile infants with eighteenth-century resources? The new legislation was remarkably vague on the issue. The governors of the institution, who were responsible for its management, therefore had to improvise. They decided that the majority of the infants would be handed over to poor women who would wet-nurse them and raise them in their own homes for a number of years in return for an annual fee. When older (usually six years of age), the children were to be returned to the hospital, a process referred to as ‘drafting’. There they would live until ready to be ‘apprenticed out’—that is, placed as indentured servants or labourers—usually at the age of twelve or thirteen.

The daunting task of recruiting hundreds of wet-nurses every year by a single organisation had never before been undertaken in Ireland. This, combined with the startling growth in the numbers of infants taken in (doubling in the first three years), placed considerable strain on the nascent Foundling Hospital.

In the early years the task of recruiting nurses fell to Elizabeth Quayle, ‘Out-Matron to the Foundlings’. Quayle started by employing nurses in the city of Dublin—poor women from the smoky lanes and courts of the city. Soon, however, the governors expressed dissatisfaction with these arrangements. One allegation was that the wet-nurses were defrauding the institution. Another concern of the governors was that parents could make contact with their children and so disrupt their Protestant religious formation. (It was assumed that the majority of the parents were Catholic.) To prevent parental access, legislation was enacted in 1735 to allow the exchange of children between the Dublin and Cork workhouses. Given the travelling conditions of the time and the likely poverty of the parents, this would amount to ‘an absolute separation’, according to one commentator. The plan was frustrated, however, by the delay in opening the Cork workhouse, which didn’t happen for another twelve years.

Other drastic measures were adopted. From 1736 all children were tattooed with a letter identifying the year of admission, together with an individual identifying number. The characters were marked on the skin with a sharp implement. Then a mixture of India ink and gunpowder was rubbed into the wound to form an indelible tattoo. Girls were tattooed on the upper arm, boys on the forearm. This practice would continue for another century. Another change was the decision to place the children with women in the countryside rather than in the city. From then on certain parishes in Wicklow, but also areas of Kildare and Meath, would become central to the operation of the Foundling Hospital. These areas were far enough away to deter visits from parents but close enough to allow the nurses to walk to the hospital in a two-day round trip, firstly to collect the child and then for its annual inspection (if it survived) and the nurse’s annual payment.

The hospital was managed by an unwieldy board of over 140 governors. Jonathan Swift was one, as were many of the leading figures of the day, including each of the Anglican clergy of Dublin.

In 1738 the first of many public scandals involving the hospital emerged when the bodies of thirteen infants were found on a sandbank by the River Camac (close to the site of the current Kilmainham Jail). The nature of the find suggested that the infants had been abandoned, or even murdered, shortly after having been collected from the hospital by nurses. Over the coming weeks yet more bodies were discovered in different parts of the city, identifiable by their tattoos.

An enquiry found evidence of mismanagement, intrigue and cover-up at the hospital, which it largely blamed on the treasurer, Nicholas Grueber (whose main business was the manufacture of gunpowder at his mills in Clondalkin). Grueber was dismissed, but no criticism was made of the governors who had overall responsibility for the hospital and little, in fact, changed. Tellingly, an incidental finding of the investigation was that 3,236 of the 4,025 children admitted in the previous eight years had died.

Despite these revelations, admissions continued to rise. It is likely that, rather than being born out of wedlock, many—if not the majority—of the children were placed in the hospital because their impoverished families were unable to feed them and hoped through their actions to secure for them a better life. There was an early spike in admissions in 1741, when they rose to 1,102, coinciding with the major famine of that year. The 1740s and ’50s were a particularly dark period in the hospital’s history, coinciding with the reign of Joseph Pursell as treasurer. The treasurer was the most senior resident officer, responsible for the management of the hospital and reporting directly to the governors. Pursell was finally exposed following another enquiry, this time in 1758, but only after he had already fled, allegedly taking a substantial amount of the hospital’s funds with him. The episode highlights a recurring theme in the hospital’s story up to then: the attribution of blame to one or a number of individuals without undertaking the fundamental necessary reforms.

There were to be more scandals and more enquiries, but throughout the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries admissions continued to climb, reaching a peak of 2,664 in 1813. In that year nearly 1,000 died in the infant nursery alone; a further 1,098 died after being dispatched to country nurses. Belatedly, the governors themselves were spurred into action. They identified the principal cause of death as the condition of the infants on arrival at the hospital. The ‘scantiness of their clothing’, the distance carried (up to 150 miles, which could take eight or nine days in an open cart), the carelessness of the ‘carrying nurses’ and the very young age of the infants were all identified as factors. It is unclear how newborn infants could be fed on such a journey, especially since several were often carried at a time, swaddled and placed on an open cart. It was probably these factors, amongst all the adversity faced by the infants, which caused the greatest mortality, as it did with other foundling hospitals.

The governors petitioned the lord lieutenant for the most radical change to the operations of the hospital in many years—its closure, but only to new admissions, for short periods of time, and only in the ‘inclement season’. Legislation was duly passed and so in February 1815, for the first time in nearly a century, admissions to the Foundling Hospital were halted, but only for two months. In the following years the hospital closed periodically for a few months each winter to admissions from country parishes. This temporarily reduced admissions, but soon they began to rise again and by 1818 had reached 2,210.

Several further changes to the legislation were introduced over the next few years, which had a limited effect on admissions. The change which was to have the greatest effect was the imposition on the parishes in 1822 of a £5 charge to be paid for each infant on arrival. The effect was dramatic: by 1823 admissions had plummeted to just 419.

There were still many who believed in the hospital’s mission and trenchantly defended it. When a parliamentary commission visited the hospital between 1824 and 1826, however, the scale of the losses became even more apparent. Figures provided by the hospital itself showed that, over the previous 30 years, 41,524 out of 52,150 children admitted had died, either in the hospital itself or while with country nurses. The parliamentary commissioners were aware of most of these figures from 1824 but, instead of acting, they first quibbled with the figures and then did not publish them for nearly two years. In their report they even recommended the continuation of the Foundling Hospital, albeit with some changes. They made no recommendation about the tattooing of the children, which continued, now with the help of a spring-loaded device designed for the purpose. Despite the commissioners’ sanguineness, it was probably inevitable, once the mortality figures were widely known, that the hospital would close, if for no other reason than the sheer embarrassment of the authorities. Eventually, in 1829 parliament did act. One hundred years after its opening, the hospital was closed to all further admissions from January 1830.

Nevertheless, while closed to new admissions, it remained responsible for the thousands of children still in its care—at least 2,000 at nurse in the country and 2,500 in apprenticeships. The numbers gradually dwindled as the children grew up, and in time responsibility for their welfare was transferred to an ‘Inspector of Foundlings’. A small minority, because of mental or physical disability, were cared for well into old age, continuing to live with the families of their old ‘nurses’. The last known survivor of the Foundling Hospital, an elderly woman, died in 1911, 181 years after the first admission.

Much information on the operation of the Foundling Hospital can be gleaned from parliamentary records. Often tragic, sometimes uplifting, the contents of these reports amount to a rich trove of social detail that brings the lives and voices of Dubliners of the period to light. Together with other sources, they allow a detailed reconstruction of the extraordinary history of the Foundling Hospital, along with glimpses of those who lived, and died, there.

Dr Mark B. Roe holds an MPhil. in History from Trinity College, Dublin, and is the author of the first comprehensive history of the Foundling Hospital.

Further reading

V. Fildes, Wet nursing: a history from antiquity to the present (Oxford, 1988).

J. Robins, The lost children: a study of charity children in Ireland, 1700–1900 (Dublin, 1980).

M.B. Roe, The least of these: the tragic story of Dublin’s Foundling Hospital (London, 2022).

N. Roman, Orphans and abandoned children in European history: sixteenth to twentieth centuries (Abingdon, 2018).