By David Mould

In July 1817 the Irish-born James Hastie, a 30-year-old East India Company sergeant, embarked on an ambitious and risky mission. From the east coast of Madagascar, he travelled by canoe and on foot to the central highlands. His destination: the court of the Ovah king, Radama, the most powerful clan chief on the island. His mission: to convince him to end the export of slaves to the plantations of the British island colony of Mauritius.

TUTOR TO RADAMA’S HALF-BROTHERS

Hastie tumbled onto the historical stage almost by accident. Born in 1786 to a Quaker family in County Cork, he received a good education but in his late teens ran away to join the British army. He shipped out to India, where he fought in the second Anglo-Maratha War (1803–5) and was promoted to sergeant. In March 1815, after Napoleon returned to Paris from exile in Elba and launched his new campaign (the ‘Hundred Days’), Britain feared a revolt by French plantation owners in Mauritius, seized in 1810 during the first Napoleonic War. Hastie’s regiment was dispatched from Bombay to reinforce the garrison.

The revolt never happened, but Hastie soon came to the attention of the governor, Robert Townsend Farquhar. During a fire that engulfed the capital, Port Louis, in September 1816, Hastie climbed onto the roof of the government house to extinguish the flames. Farquhar, noting that he was well educated, appointed him as tutor to Radama’s two young brothers, who had recently arrived on the island.

The education of the princes was part of Farquhar’s strategy to form an alliance with the rising military power in Madagascar. By the end of the eighteenth century Radama’s father, Andrianampoinimerina, had subdued the rival clans of the central highlands and created a powerful kingdom. On his deathbed, he told his seventeen-year-old son that his mission was to expand the realm to the east coast. The impetuous, warlike Radama, who had heard stories of Napoleon’s campaigns from French slave-traders at his father’s court, needed little encouragement.

MADAGASCAR AND THE SLAVE-TRADE

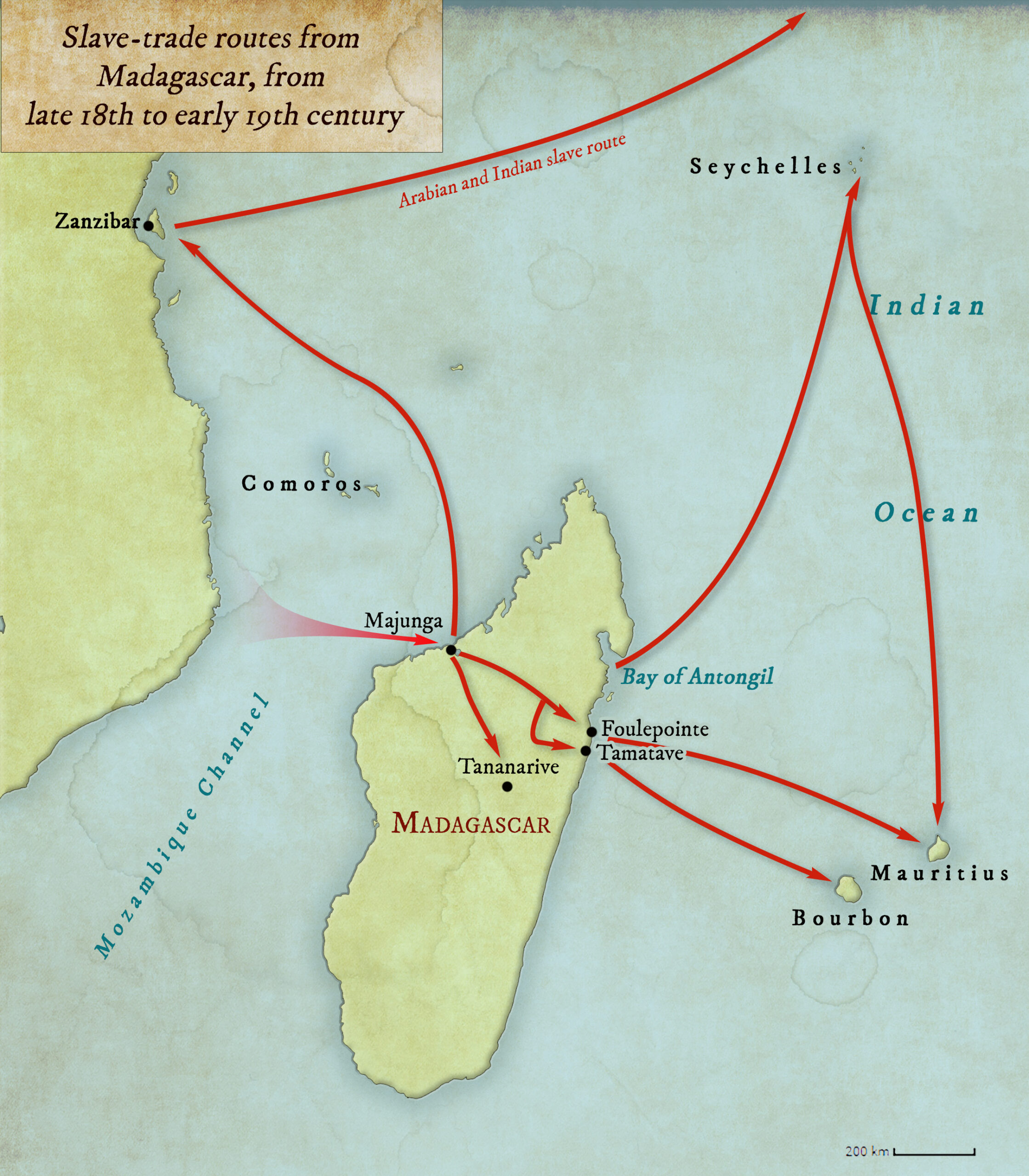

Madagascar was a key transit point in the extensive slave-trading network of the south-west Indian Ocean. Arab traders brought African slaves across the Mozambique Channel to the west coast; some were shipped north to the slave market of Zanzibar and on to Arabia, Persia and India, or marched across the island to the east coast. Others were captured in island clan warfare and sold to the French slave-traders who controlled the trade from east coast harbours to the plantations of Mauritius and Bourbon (today Réunion).

In 1807 Britain’s parliament banned the slave-trade to its colonies. Like colonial administrators in the Caribbean, where plantation economies depended on slave labour, Farquhar found himself in a difficult position. London demanded an immediate end to the slave-trade but the French settlers, who had been allowed to keep their plantations and slaves, continued to deal with traders who smuggled their human cargo into isolated coves and inlets under the cover of night.

Farquhar protested that he did not have enough soldiers to police the plantations, or the ships to patrol the seas. London was unmoved. Without the resources to mount a military operation, Farquhar decided on diplomacy. If he could forge an alliance with the Ovahs, he could cut off most of the slave exports at their source. He knew that Radama, his nobles and army commanders counted on the sale of war captives as their main source of income. What would the king want in exchange for a treaty?

HASTIE IN CHARGE

In July 1817 Hastie accompanied the princes on their return to Madagascar. When Thomas Pye, the agent chosen to lead the mission to Radama, fell ill with malaria, Hastie took his place. With horses and gifts for the king, and accompanied only by porters, he set off by canoe across the coastal swamps.

The region had been ravaged by warfare between Radama’s forces and local clans. Both sides burned villages and crops, forcing inhabitants to flee into the forest. ‘[H]unger can be read on every face; they eat the fruits of any tree that bears it and roots that grow in the water,’ Hastie wrote in his diary. ‘Money has no value here, since one cannot obtain anything.’ As the party began the ascent through the tropical rainforest to the highlands, the trail became more arduous. ‘The road is nothing but ascents and descents all the time. Passed six mountain streams swelled by the rain. A thick fog prevents us from seeing far … If this is the good season for travel in this country, I assert that it must be impossible to proceed in the bad.’

INTERNAL POWER STRUGGLE

Hastie arrived in the Ovah capital, Tananarive (today Antananarivo), after a 28-day journey and was received with ceremony by the king. Radama symbolically placed the envoy at his side for rituals and animal sacrifices to mark the start of the Malagasy new year. Hastie realised that the king was using him as a tool in an internal power struggle, but he had to play along to win his confidence. The nobles and army commanders who relied on the sale of war captives for income opposed an alliance with the British. They also feared that Radama, who openly expressed his admiration for foreign monarchs and abandoned traditional dress in favour of European-style military uniforms, was undermining traditional Ovah culture and religion.

For the next two months Hastie, who had no formal diplomatic training, lived by his wits as he navigated the politics of the Ovah court. Through an interpreter, he told Radama that to be regarded as a ‘civilised king’ he had a moral obligation to halt the slave-trade. Hastie did not, however, raise objections to the institution of slavery, arguing that the kingdom would prosper if it kept its war captives at home to build roads and work in agriculture and industry rather than exporting them.

The negotiations dragged on, sometimes lasting long into the night and lubricated by wine and cognac. Hastie had to take a gamble. Without formal authorisation from Farquhar, he proposed compensating Radama for loss of slave-trade income with munitions and supplies. Radama instructed his ministers to travel to the east coast to sign a treaty with Farquhar’s representatives in October 1817. Farquhar, satisfied that he had achieved his goal, returned to Britain on leave.

‘FALSE AS THE ENGLISH’

Farquhar’s successor, the acting governor, did not trust the Ovah king. He reneged on the deal and fired Hastie as the British envoy. The slave-trade resumed. The treaty was revived in 1820,when Farquhar returned to Mauritius and sent Hastie back to meet with Radama. It was not an easy sell. The king told him that he felt betrayed, saying that his people had adopted a new phrase to describe cheaters and liars—‘false as the English’. It took more gifts, flattery and hard bargaining for Radama to agree to resume the alliance.

The treaty was a deal with the devil: in return for the slave-trade ban, the British trained Radama’s army and supplied muskets, gunpowder and uniforms, allowing him to expand his dominions. At the same time, the British turned a blind eye to the internal slave-trade. The alliance not only helped Farquhar satisfy London that he was stopping the slave-trade but also kept out the French, who were again vying for power in the region. The British stroked Radama’s ego by formally recognising him not as a clan chief but as ‘king of Madagascar’.

Hastie became the British envoy to Madagascar and Radama’s trusted adviser, joining him on military expeditions to subdue rival clans and to expel Arab slave-traders. The campaigns, which lasted several months, took a heavy toll on the conscript army, with more deaths from heat, famine and sickness than from fighting. Returning from the north-west campaign in August 1824, Hastie wrote: ‘The march today lay thro’ rice fields and swamps … not air enough to shake the highest leaf of the tamarind tree under which hundreds, unable to proceed, sought a momentary shelter. Not one tenth of the division under arms, one quarter sick and two thirds employed in helping them along.’

Hastie made lasting contributions to the Ovah kingdom. He undertook expeditions to the east coast to select sites for commercial and trading settlements. He introduced new agricultural crops and mulberry bushes for silk production, brought in artisans to teach trades, negotiated for the London Missionary Society to open schools, introduced social reforms and supported Radama in his ongoing power struggle against traditionalist factions.

DEATH

After suffering a series of accidents, Hastie died in Tananarive in October 1826 at the age of 40, leaving a widow and a one-year-old son. Radama was devastated; he ordered his burial in a traditional stone tomb with full military honours, a ceremony usually reserved for members of the nobility. Sir Mervyn Brown, a former UK ambassador and historian of Madagascar, described Hastie as ‘one of the most important and attractive figures in the history of Anglo-Malagasy relations’.

Hastie’s historical significance outlasted his career. The British authorities in Mauritius needed intelligence on an island to which few Europeans had travelled, and Farquhar instructed Hastie to record his observations in detail. His diaries for the period from 1817 to 1825 (now in archives in Mauritius and London) offer the most comprehensive early nineteenth-century account of Madagascar. Hastie not only reported on internal politics and Radama’s campaigns but also described landscape and topography, agriculture, timber and mineral resources, trade routes, anchorages, house construction methods and religious practices. Mission to Madagascar is based on these diaries, one of them recently discovered, along with other primary sources, including letters and political and military dispatches.

David Mould is Professor Emeritus of Media Arts and Studies at Ohio University, USA.

Further reading

R.B. Allen, European slave trading in the Indian Ocean, 1500–1850 (Athens, Ohio, 2015).

M. Brown, A history of Madagascar (Princeton, 2000).

G. Campbell, Aneconomic history of imperial Madagascar, 1750–1895: the rise and fall of an island empire (Cambridge, 2005).

P.M. Larson, History and memory in the age of enslavement: becoming Merina in highland Madagascar, 1770–1822 (London, 2000).

D. Mould, Mission to Madagascar: the sergeant, the king, and the slave trade (Charleston, WV, 2023).