By Kyle McCreanor

A tale of false passports, international espionage and grandiose plots in Jazz Age Paris, the story of two Irish republicans aiding a joint Basque and Catalan nationalist initiative to establish independent republics by arms has been shrouded in secrecy and largely unknown to historians. This article sheds light on the intriguing case of two Irishmen—IRA commander Ernie O’Malley and international activist Ambrose Martin—who aided an abortive paramilitary operation against the Spanish government. In the wake of the Irish Civil War, the underground government of the Irish Republic continued to seek international recognition in competition with the Irish Free State, rendering Éamon de Valera and his envoy in Paris, Leopold Kerney, averse to close ties with ‘dangerous friends’, as they described this contingent of Basques and Catalans. Nonetheless, de Valera and Kerney were aware of the Basque–Catalan plot, condoned the unofficial involvement of Ambrose Martin and privately calculated that independent Basque and Catalan states ‘might possibly be able to render us good service’.

PRIMO DE RIVERA DICTATORSHIP IN SPAIN FROM 1923

In September 1923 the Spanish parliamentary government was overthrown in a military coup, which installed Captain-General Miguel Primo de Rivera as dictator. While moderate regionalist parties in certain parts of the country were permitted, pro-independence nationalist organisations in Galicia, the Basque Country and Catalonia were outlawed. Many radical nationalists crossed the border and made their way to the traditional home for political exiles worldwide: Paris. From the French capital, Catalan separatists and their Basque co-conspirators began to formulate a ‘rising’—inspired in part by the Irish example of 1916—that would coincide with the proclamation of independent republics.

The primary force behind the rising plot was Estat Català (Catalan State), founded in 1922 by the elderly Lieutenant-Colonel Francesc Macià and operating a headquarters and political office in Paris. Macià, like many Catalan nationalists, was an ardent admirer of Irish republicanism. Estat Català took inspiration from the Irish example. It was intended to be a national movement, being both a means of broad political organisation and a paramilitary body, akin to Sinn Féin and the IRA. They needed only an Easter Rising of their own. ‘The liberty of peoples has only ever been bought at the price of blood’, Macià tellingly wrote in 1925.

The exiled Catalan leader also spearheaded a political initiative to form an alternative to the League of Nations, which he regarded as an imperialist farce. The so-called ‘League of Oppressed Nations’ was to include the likes of Catalonia, the Basque Country, Morocco, India and Ireland. To this end, a Basque delegate arrived in Dublin in 1924 to personally deliver an invitation to Éamon de Valera, but de Valera and Leopold Kerney agreed that it was politically best to resist official association. ‘Of course we sympathise with all, but a formal League is another matter,’ de Valera wrote to Kerney. Such diplomatic caution was warranted when the British, French, Spanish and Italian intelligence services were all keeping close tabs on the activities of Macià and company, who travelled to the Soviet Union in 1925 to seek funding from the Comintern.

AMBROSE MARTIN, INTERNATIONAL IRISH REPUBLICAN

The first Irishman to assist Estat Català was a roving young Irish-Argentinian named Ambrose Victor Martin. In 1914 Martin was sent from his native Argentina to attend St Finian’s College in Mullingar, in his grandmother’s native Westmeath. Caught up in the revolutionary tumult of the day, the teenaged Martin made a name for himself as a fiery orator on Sinn Féin stages around the county. Ultimately, in 1919 he was deported by the authorities back to Argentina, where he remained for over two years. His hometown of Suipacha was a small, rural community settled in large part by Irish and Basque immigrants. This unique circumstance likely explains Martin’s next destination—the Basque Country, where he claimed to be visiting ‘old friends’. Arriving in the industrial port city of Bilbao in April 1922, Martin spent four weeks regaling packed conference halls of attentive Basque nationalists with emotive speeches on the Irish revolution. Having followed events in Ireland with great interest since 1916, radical Basque nationalists were ecstatic to enjoy the visit of an ostensible Irish republican hero (unbeknownst to them, his credentials were grossly overstated). Going forward, Martin was positioned as the key link between Irish republicans and Basque nationalists.

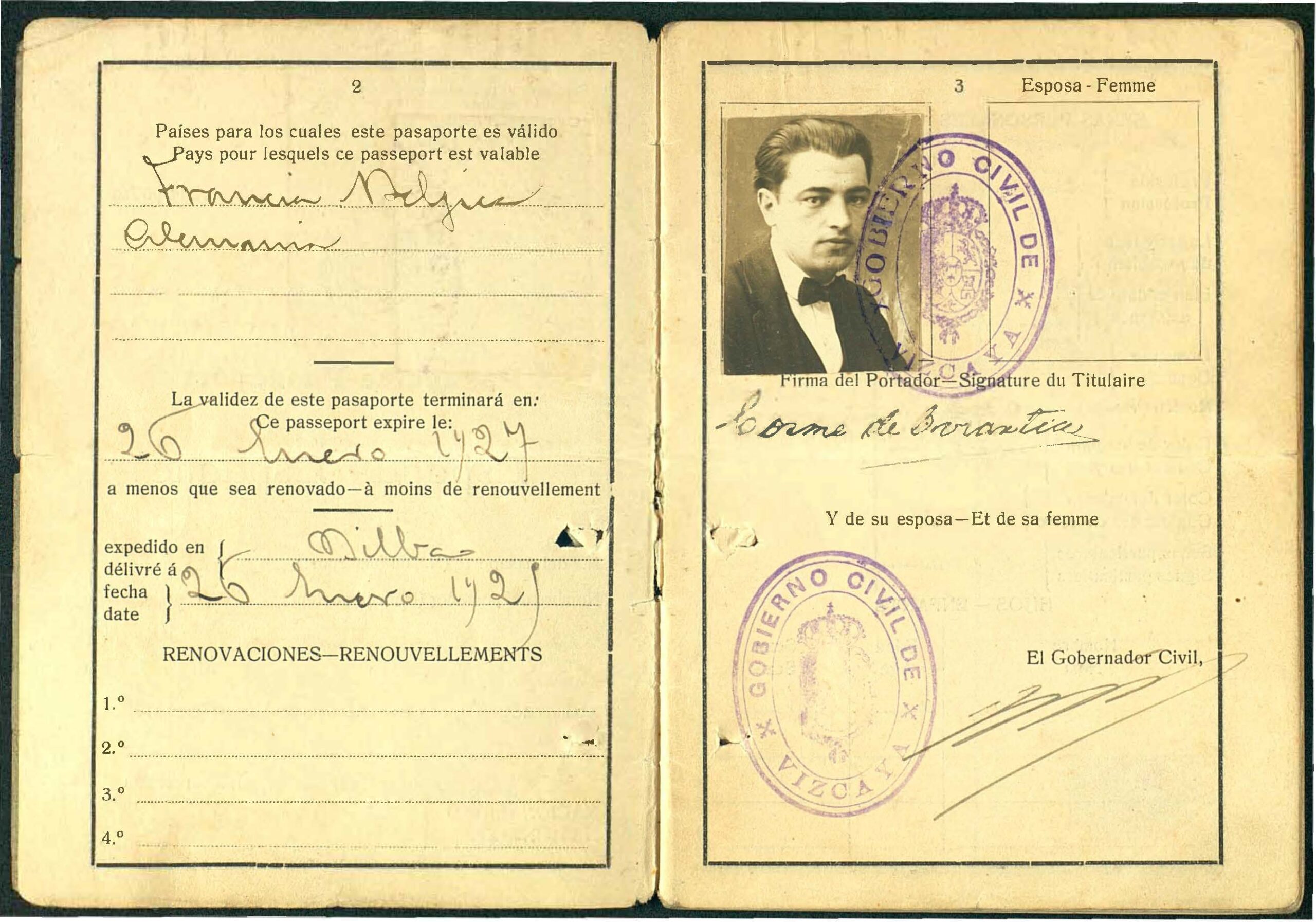

Ambrose Martin returned to Ireland shortly before the outbreak of the Civil War, though in late 1924 he left for the Basque Country once again. His old Basque nationalist connections hosted him, set him up with fake documents and took him to secret gatherings in the mountains. Under the repressive dictatorship in Spain, with many of his Basque comrades arrested, awaiting trial or already having fled the country, the young Irish-Argentinian ended up in France in early 1925. Some of his Basque associates began cooperating with the similarly exiled Catalans in Paris, discussing a possible uprising of their own to occur in tandem with that in Catalonia.Martin was soon to join them in the dynamism of 1920s Paris, a magnet for artists, dissidents and exiles—and host also to James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway, Pablo Picasso, Ezra Pound and Ho Chi Minh. ‘My dearest wife,’ Martin wrote back to Ireland from Paris in February 1925, ‘I cannot give you a description of my work as promised in case this letter might fall into other hands …’.

One of the Catalan plotters recalls in his memoir that an eccentric young Irishman known to them only as ‘Ambrosi’ slept in their attic with his gun, ranting about the Black and Tans coming to find him in France. The same account reports that Ambrose Martin’s stay there was facilitated by de Valera himself. Martin had evidently made connections in high places. Introduced at one event as a ‘republican soldier’ and ‘distinguished friend’ of Francesc Macià, Martin stayed at the Estat Català headquarters for a short time and penned a series of notes for them on IRA tactics. At one point he appeared to be helping the Basque leg of the planned uprising; Leopold Kerney passed on a request from Martin to Dublin in July 1925, asking for ‘a couple of furniture polishers, members of IRA or at least men who have taken an active part for Irish Republic; we will not have any others. Their return fare from Dublin would be paid. Work guaranteed as soon as they arrive in Bilbao. […] The work is to polish all kinds of high class furniture.’ In the end, no IRA men arrived in the Basque Country to polish furniture (in not-so-secret code), as Kerney eventually lost contact with Martin, and Basque involvement in the slow-going plot withered away.

ERNIE O’MALLEY ON VACATION

The second Irishman to aid the Basque–Catalan rising plot was IRA commander Ernie O’Malley. Famed for his military acumen during the Irish revolution and his literary achievements later in life, O’Malley’s brief involvement with Basque and Catalan nationalists in 1925–6 is only a minor episode in his storied career about which he said very little. Among the last to be dismissed from Free State custody after the Civil War, O’Malley began an extended stay in Europe in February 1925 to recuperate from his war wounds. His sojourn commenced in the sunny Catalan capital, Barcelona. Even far from home, however, O’Malley could not fully escape the world of political and military intrigue. His journal entries on the local culture, scenery and gastronomy belie the clandestine scene into which he was apparently drawn. Some years later, he reported that a local Catalan had asked him to assist an unfolding plot and that he was ‘put in touch with a certain section in Spain which might be likened to the IRA’. According to republican comrade Peadar O’Donnell, the IRA Army Council had authorised O’Malley to liaise with Catalan separatists.

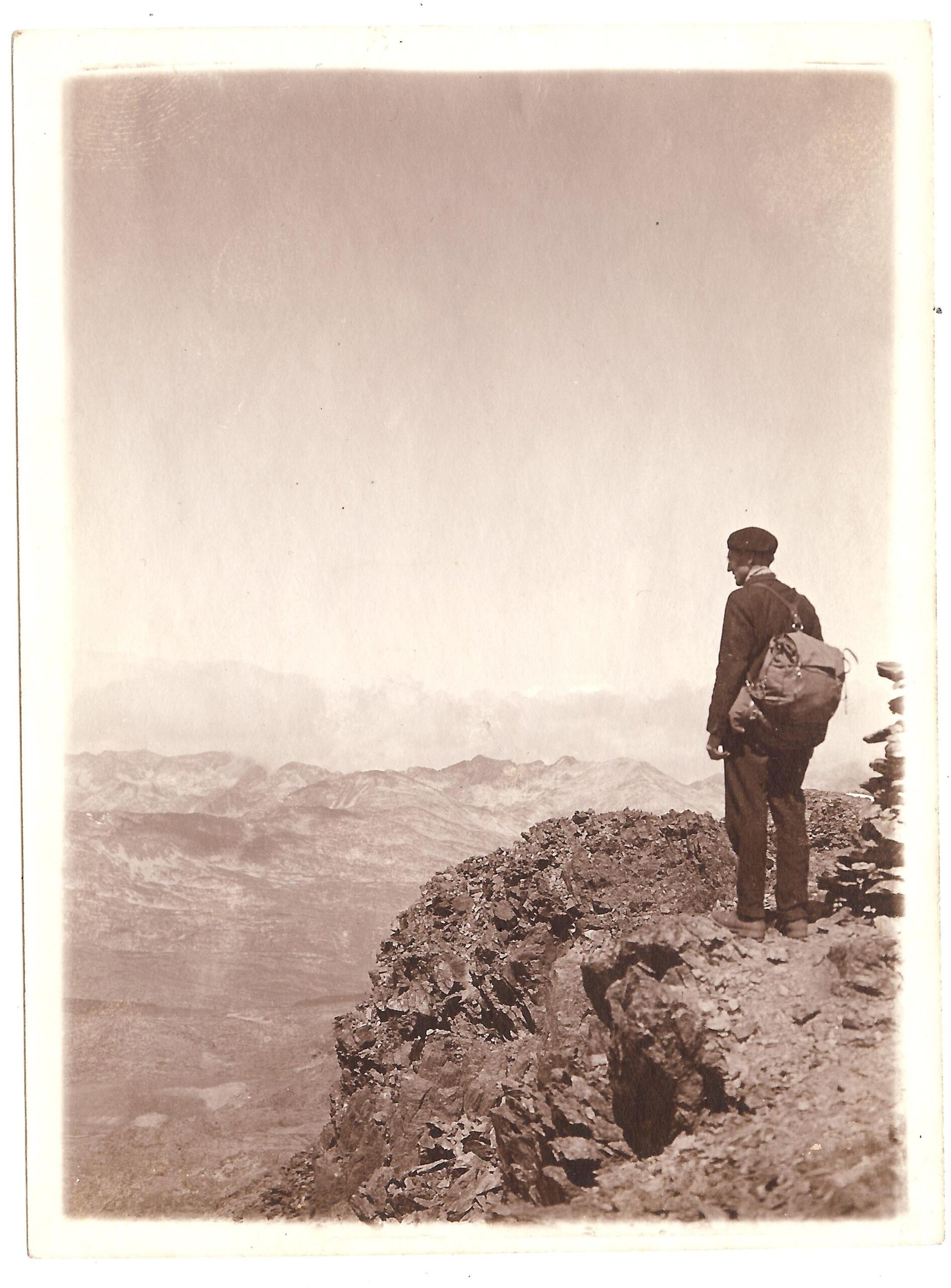

O’Malley recorded a visit with an unnamed prominent Basque nationalist on one of his mountain excursions—likely Eli Gallastegi, a close friend of Ambrose Martin and the de facto leader of the radical Basque nationalists, who was then living in the French Basque Country to avoid arrest in Spain. Gallastegi headed the faction of Basque nationalists that was in talks with Macià to organise their own armed revolt in their corner of the Pyrenees. Evidently O’Malley was forging connections with the key players in the still-vague insurrectionary plan. By 1926 O’Malley had made his way to the heart of the action in the French capital. Fellow republican Seán MacBride, then back in his native Paris, hosted O’Malley as a sporadic guest at his flat. In his memoir, MacBride writes that O’Malley was ‘a little bit odd’ and would wander restlessly around the city. A sympathetic acquaintance in the French intelligence service informed him that his guest was ‘acting as chief military adviser to Colonel Macia, the leader of the Catalan separatist government here in Paris’. MacBride then journeyed out to the headquarters of Estat Català, where Francesc Macià keenly acknowledged the assistance of their ‘good friend’ Ernie O’Malley.

O’Malley only ever made vague allusions to his involvement in planning an insurrection against the Spanish government, likely keeping mum for political and operational reasons. By his own account, O’Malley went ‘to help the Catalan movement for independence’. The nature and extent of his assistance remains uncertain. While Ambrose Martin left a paper trail and is recorded in one of the plotters’ memoirs, there is unfortunately no trace in any Basque or Catalan source of their alleged chief military adviser from the IRA. Martin ran in the same circles as O’Malley and later hinted that his ‘connection with the Basques was something similar to his own’. O’Malley would have had considerable tactical expertise to offer Macià, who envisioned a protracted guerrilla campaign in the Pyrenees should their uprising be initially unsuccessful. Having an IRA commander and elected member of the Dáil assist such an operation should be considered one of the most significant and dramatic transnational contacts of the republican movement in this era.

THE FATE OF THE PLOT

In November 1926, Francesc Macià and his would-be Catalan Army were arrested by French authorities in the town of Prats de Molló before they could march across the border into Spain. Ambrose Martin had earlier abandoned the operation, thereafter known as the ‘Prats de Molló plot’, telling them that he had been ‘recalled to Ireland’. In reality he opted to pursue a more stable vocation in Paris, working in the home of an aristocratic family. Ernie O’Malley returned to Ireland before Estat Català launched its ‘liberation’ of Catalonia—a plan so poorly conceived in the end that some have speculated that it was designed to fail, along the sacrificial lines of the 1916 Easter Rising. Macià, nonetheless, after several years in exile would return to govern Catalonia as president of the restored autonomous government in 1931.

Despite de Valera’s caution, solidarity on the ground gave rise to Martin and O’Malley becoming close associates of Macià and various other key Catalan and Basque radical nationalists. There was little that the leadership of the wounded republican movement could do to prevent such contacts, and Kerney reminded de Valera that they were desperate for what support they could get. While an independent Catalan republic formed by Macià—with secret support from two sympathetic Irishmen—might have been a useful ally, the failure of the Prats de Molló plot was of little importance to them. Having maintained distance, the notional republican government continued to carefully present itself as representing a state rather than as a kindred spirit of foreign paramilitary groups. Spain, judged to be a ‘natural ally’ of Ireland by the republican Department of Foreign Affairs, perhaps never knew of the minor Irish involvement in the Prats de Molló plot.

Kyle McCreanor has an MA in History from Concordia University, Montréal.

Further reading

G. Keown, First of the small nations: the beginnings of Irish foreign policy in the interwar years, 1919–1932 (Oxford, 2016).

S. MacBride (ed. C. Lawlor), That day’s struggle: amemoir 1904–1951 (Dublin, 2005).

H. Martin & C. O’Malley, Ernie O’Malley: a life (Dublin, 2021).