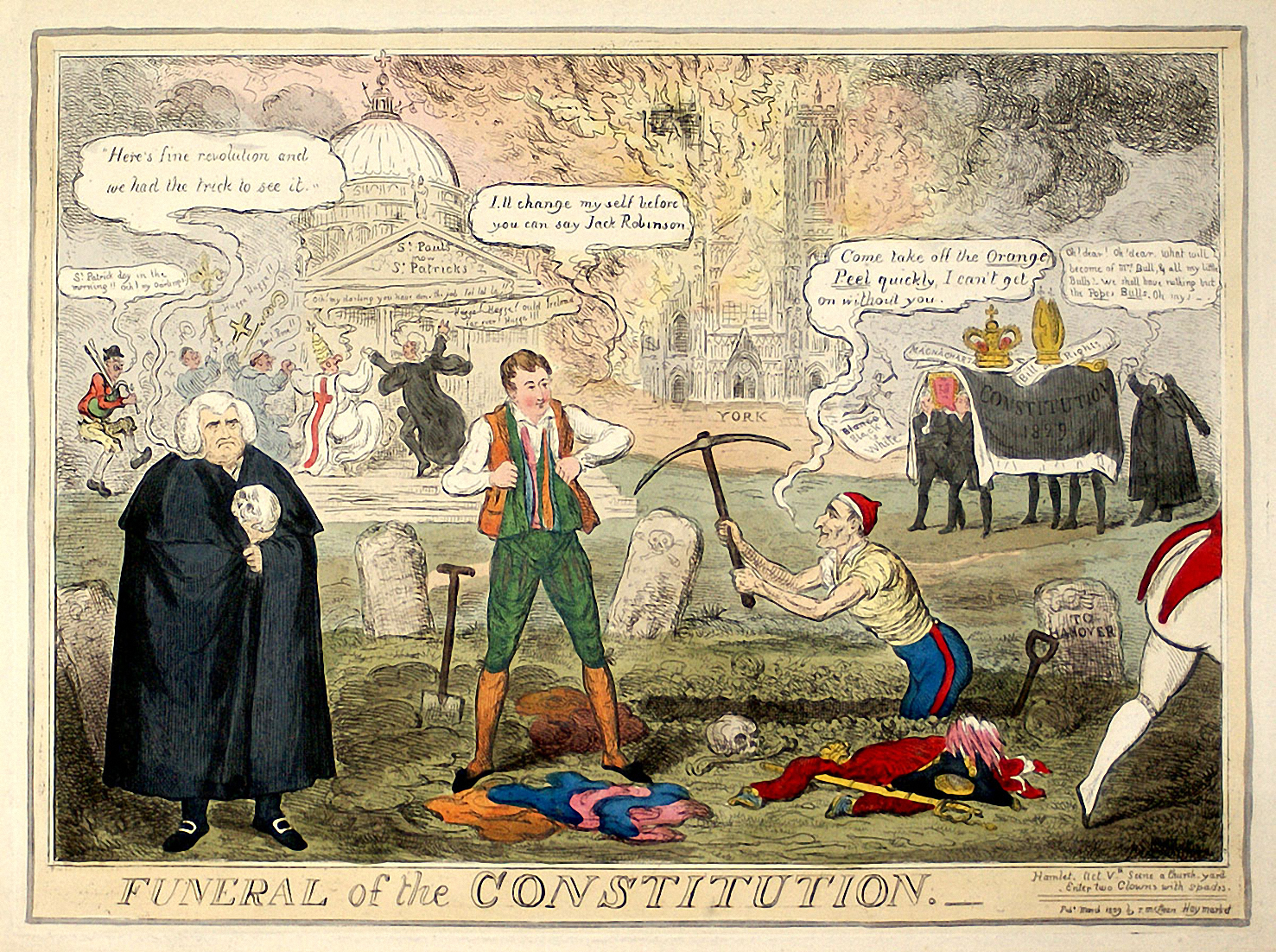

Sir,—Following Sylvie Kleinman’s review in the last issue (HI 33.1, Jan./Feb. 2025) of Nicholas K. Robinson’s Caricature and the Irish, I would like to offer up this crowded exposition of Catholic Emancipation (which I have hanging on a wall at home).

In 1829 Thomas McLean (1788–1875), a publisher and dealer in London’s Haymarket, published ‘FUNERAL of the CONSTITUTION’, by the enactment on 13 April 1829 of the Act for the Relief of His Majesty’s Roman Catholic Subjects, 10 Geo.4.c7, removing various sectarian oaths to take public offices; and he made a play on the graveyard scene from Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Front and centre is Robert Peel, with his green and orange clothes, being told by the prime minster, the Duke of Wellington (with pickaxe), to assist in digging the grave for the approaching funeral of the pre-1829 British unwritten constitution. On the left-hand side stands William Howley, the archbishop of Canterbury, lugubriously clutching a skull and muttering ‘I told you so’ words.

To the right is shown the funeral of the old constitution bearing the symbols of Crown and State, and Mr [John] Bull mourning that he and his little Bulls—future generations—will have nothing but papal bulls in the future.

The Duke of Wellington urges Robert Peel, then home secretary: ‘Come take off the Orange Peel, I can’t get on without you’, a sure reference to the about-turn necessitated by Daniel O’Connell’s County Clare election victory, a fear of civil commotion and an immediate dropping of the ardent Protestant tenets they had held just prior.

King George IV, despite his popular visit to Ireland in 1821, opposed Catholic Emancipation until forced. He was also ruler of the German state of Hanover and would threaten to retire there in the face of undesired legislation. His ample significant rear (to the right) makes for easy identification.

Here are the feared consequences of Catholic Emancipation: St Paul’s Cathedral in London is renamed St Patrick’s, and around the building dances, from left to right, an Irish piper calling ‘St Patrick day in the morning, Oh! my darlings!’; a cluster of men and monks, ‘Huzza, Huzza!’; Pope Pius VIII, with his triple tiara, who had no hand in promoting Catholic Emancipation in the United Kingdom but nevertheless takes to Irish idiom with ‘Och! My darling you have done the job, fol la la!!’ to Daniel O’Connell, who is also dancing and wearing his lawyer’s wig and gown.

As if Catholic Emancipation was not shock enough for the establishment, the second cathedral in status for the religious ascendancy, York Minster, had been deliberately set on fire on 1 February 1829 by Jonathan Martin, who held a hatred of the establishment, describing clergy as ‘the vipers of hell’. He was caught and declared insane at trial. On the right (left of the symbols of the constitution) appears to be Martin with his torch, and a paper bearing ‘Black is White’, the black crossed through and replaced by ‘Blanco’, a reference to José Maria Blanco y Crespo, who became known as Blanco White (1775–1847), a Spanish theologian and priest who came to England in the 1820s, opposed Catholic Emancipation and was somewhat of a celebrity of the day. In 1831 Blanco White accompanied Richard Whately on his appointment as archbishop of Dublin as tutor to his son.

The image throughout is evidently for English and Protestant viewers, all enough for T. McLean to compact into a satirical print.—Yours etc.,

JOHN STOCKS POWELL

Portarlington