Ulster Museum, Belfast

By Donal Fallon

Beyond being physical spaces, our museums and galleries also exist in the digital realm. Few have embraced the internet and its possibilities as well as the Ulster Museum. A visitor to their website will encounter the oral history project Voices of ’74, interviewing those who lived through that turbulent and dramatic year. The intention, the visitor reads, ‘was to gather a variety of perspectives and collect memories, not to provide answers’. That is an ethos that runs throughout the Ulster Museum and its handling of recent and contested histories.

While the physical exhibition Drawing Support: Murals, Memory and Identity is now over, it is still possible to explore this exhibition online, thanks to the ‘curator tour’ featuring Bill Rolston in conversation with Rebecca Laverty from the Museum. Since the early 1980s, Rolston (a sociologist who refuses the title of photographer) has photographed the political murals of Northern Ireland, publishing a series of books entitled Drawing Support. In the introduction to the first book in the series, published in 1992, Rolston argued that it was important to chronicle these murals not merely for what they said about the past but also for the insights they gave into contemporary and shifting politics: ‘Through their murals both loyalists and republicans parade their ideologies publicly. The murals act, therefore, as a sort of barometer of political ideology. Not only do they articulate what republicanism or loyalism stand for in general, but, manifestly or otherwise, they reveal the current status of each of these political beliefs.’

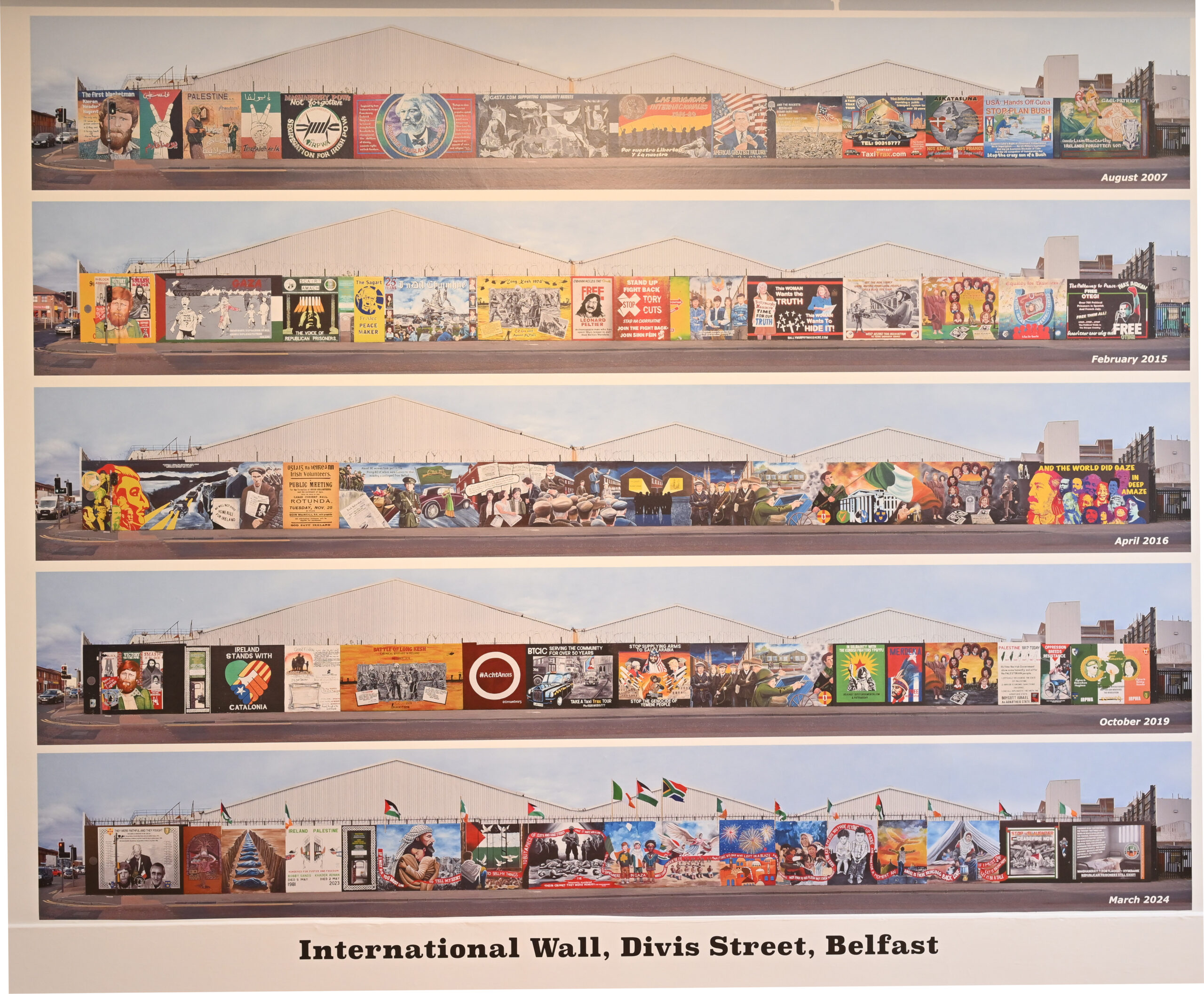

Located in the Belfast Room space, the exhibition consisted of framed archival shots from Rolston’s collection, along with interpretation and an interesting use of timelines—showing, for example, the same Lower Falls Road wall (known as the International Wall) over different periods. Largely dominated by Palestinian solidarity murals today, we see the wall as it responded to events in real time. ‘It’s not a gallery’, Rolston tells Laverty, ‘but an ongoing political statement.’

The murals presented in this exhibition are part of the everyday lives of thousands of people, but people may be unfamiliar with what exists only a few streets away, celebrating very different political traditions and cultures. On a recent trip to Belfast to visit Banana Block, an events and cultural space on the Newtownards Road, I took the opportunity to walk back into the city centre, passing murals honouring Harland & Wolff, Edward Carson and the history of women’s labour in Belfast.

Rolston pinpoints 1981 as a significant year in the story of murals. While there had been occasional republican murals before, the H-Block hunger strikes galvanised a solidarity movement which began painting walls, with Rolston estimating ‘probably 300 in the spring and summer of 1981’. Rolston began taking photographs, and ‘the hobby that got out of hand’ would go on to create five publications. Within loyalism there was a much longer tradition of mural-painting, with the earliest murals pre-dating partition. Many were painted to coincide with annual commemorations of the Battle of the Boyne. Rolston argues that, while there was a ‘vibrant culture’ within nationalism, ‘it took place in the private space of church halls and sports grounds owned by the Gaelic Athletic Association. It was much more contained than the expansionist unionist culture of the Twelfth of July.’

Rolston dates one well-known mural, Bobby Jackson’s tribute to King William III in the Fountain area of Derry, to 1916. Later, when the street was being redeveloped in the 1960s, ‘the locals were happy to agree to the redevelopment process, but they insisted they want to reinstate the mural at the end’. Originally standing at the cul-de-sac wall in Clarence Place, below Fountain Street, Bobby Jackson’s mural has not only been moved but has also been repainted and reinterpreted by his son and grandson. Also from Derry, Rolston presents a mural commemorating the Battle of Messines. In it we see John Meeke, who signed the Ulster Covenant and served with the 36th (Ulster) Division, offering medical assistance to the wounded nationalist MP Willie Redmond, who would die of his wounds. ‘My men are splendid and we are pulling famously with the Ulster men’, Redmond wrote only days before his death. Murals like this, showing shared histories, are becoming increasingly common. In the latest edition of the Drawing Support series, the front cover depicts a mural on Belfast’s Ormeau Road that highlights the story of the Corr family. Within one family, three siblings participated in the Easter Rising in Dublin while two fought in the First World War.

For some, the murals that dot the landscape of Northern Ireland are an unwelcome reminder of the past. In the Irish Times, Newton Emerson felt that ‘violence is lauded through the same handful of tired images and grievances are listed through trite sloganeering’. But the violence or guns appearing on murals in recent times are largely drawn from the distant past, depicting the barricades of Easter Week or the trenches of the Somme. Significantly, Rolston’s exhibition runs right up to the contemporary landscape, demonstrating how street artists are now having an impact on the built landscape. These murals are not about commandeering space or marking territory, with Rolston telling us that ‘they’re about spectacle’, and are often tied to commercial businesses. A mural honouring the cast of Derry Girls has fast become a favourite in Derry, while Belfast’s social history has been well represented in recent times. Still, the fallout around a mural painted for hip-hop group Kneecap (described by one politician as ‘grooming a new generation of young people with insidious messaging’) is a reminder that the walls of Northern Ireland can still be contested spaces.

Online curator tour @ www.ulstermuseum.org/digital-tour/bill-rolston-curator-tour.

Donal Fallon is the presenter of the ‘Three Castles Burning’ podcast and the author of Three castles burning: a history of Dublin in twelve streets.