By Daragh Fitzgerald

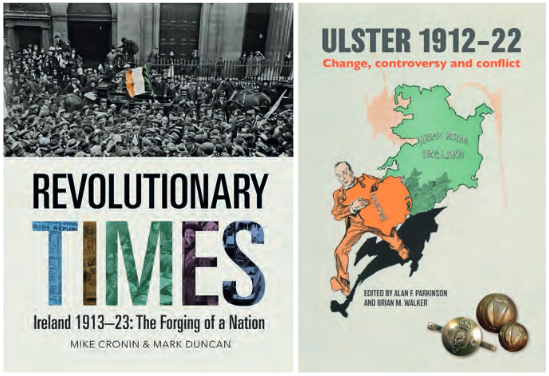

As we approach the 100th anniversary of the Boundary Commission and the end of the Decade of Centenaries, it is worth reflecting on Laura McAtackney’s insight that commemoration is the ‘deliberate act of remembering the past, at a particular time and place, as a symbolic act in the present’. Shifting relations with our neighbouring island made the latter half of the Decade, which was always going to be more divisive, all the more hazardous. The government hardly covered themselves in glory with the ‘Tan-gate’ débâcle and Covid hindered later commemorations, although this was undoubtedly seen by some as a silver lining. What was certainly a successful State endeavour was the democratisation of the Bureau of Military History witness statements and pension files, which has enabled the proliferation of myriad books and articles with a more nuanced picture of the revolutionary period and has deepened our understanding of the time. Revolutionary times—Ireland 1913–1923: the forging of a nation is perfect for anyone seeking to immerse themselves in this transformative decade when everything changed utterly. The book is structured chronologically, punctuated by essays analysing particular issues and themes as they arise, and charts the events of the period as they occurred, big and small. While 1916 famously featured the Rising and the Somme, it was also the year in which Irish dentists were permitted to use cocaine as an anaesthetic.

Ulster 1912–22: change, controversy, and conflict is a collection of essays assessing this period and how it affected Ulster in particular. Richard Grayson’s contribution problematises the memory of the Great War in the North, which has centred almost entirely on the 36th (Ulster) Division’s experience of the Somme, specifically the opening hours of the battle. The first of July 1916 was the bloodiest day in the history of the British Army, and that this episode holds a special place in the hearts of many in Ulster is unsurprising, given the sheer scale of the slaughter on what was the province’s worst day of the war in terms of losses. However, the same could be said about Dublin, where the battle does not have the same resonance. Popular perceptions hold that the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) joined the 36th en masse, but simple maths demonstrates this to be untrue: the division numbered about 16,000 men, the pre-war UVF around 100,000. Some of the latter were too old to fight; many worked in key war industries, while others were called up to different divisions as reservists. By 1917 half of the original cohort remained, and following a restructuring of the army in 1918 the division had 3,000–4,000 Catholics, though I won’t hold my breath waiting for their mural. In fact, some nationalist ex-servicemen were targeted by sectarian murder gangs like the Ulster Imperial Guards, themselves comprised predominantly of ex-servicemen, upon their return from the frying-pan of the Western Front to the fire of Belfast in 1920–2.

Edward Burke’s Ghosts of a family: Ireland’s most infamous unsolved murder, the outbreak of the Civil War and the origins of the modern Troubles conveys the atmosphere of intense fear and horror felt by nationalists in Belfast during the ‘pogrom’ and focuses on the most notorious incident, the McMahon killings. After 1am on 24 March 1922, five men, four wearing Special Constabulary uniforms according to surviving members of the family, burst into the McMahon home, rounded up the men of the house—patriarch Owen McMahon, six of his sons and his employee Edward McKinney—and opened fire. Eleven-year-old Michael hid under the table trembling in fear, while nineteen-year-old John survived, but Owen, four other sons and Edward were all murdered. The McMahons were a ‘respectable’ middle-class family with no links to republican paramilitaries, and Owen was actually a personal friend of Joe Devlin. The inspector in charge of the case, DI William Lynn, concluded in his report that there was no evidence of police involvement, and nobody was ever charged. IRA investigations pointed the finger at DI John Nixon, but Burke suggests that the murders may have been organised and led by another hard-line loyalist, David Duncan. The lacklustre investigation into the killings and the sectarian violence of the Specials provoked significant grievances and resentment amongst Catholics in the North, and when they were ultimately disbanded in 1970 it was too late: another cycle of violence had begun.

Chris Lawler’s Robert Barton: a remarkable revolutionary is the first biography of a forgotten man of the revolutionary era, remarkable considering that he was a signatory of the Treaty in 1921. Lawler previously participated in a History Ireland Hedge School on Barton in 2021, which he says inspired him to write the book. Born into an élite Protestant unionist family in Wicklow, Barton grew up in Glendalough House in the company of his older orphaned cousin, Erskine Childers. Decades after playing together on the estate, they would both be at 10 Downing Street as part of the Treaty negotiations, where Barton was the most hesitant of signatories. Like all republicans worth their salt, Barton was ‘out’ in Easter 1916—though in the British Army cohort who arrived at Kingstown. Barton had no uniform and was sent home, and thus saw no action. By this stage, however, his politics had already dramatically shifted from those of his upbringing. He remained in the British Army until the summer of 1918, a few months before his election as a Sinn Féin MP.

1588: The Spanish Armada and the 24 ships lost on Ireland’s shores examines another event in the history of these islands that demonstrates the unreliability of historical memory. Catholic superpower Spain launched an invasion of England in 1588 owing to the latter’s support for Dutch rebels in the Spanish Netherlands and piracy on Spanish ships. Skirmishes in the Channel culminated in the Battle of Gravelines and ultimately in the failure of the Armada. Memory across the water constructs this as a David and Goliath struggle in which plucky England smashed the Armada, but only one Spanish ship was sunk by the English; over two thirds of the fleet made it back to Spain, while the others were sunk by ‘Protestant winds’ smashing them into Ireland’s jagged Atlantic Coast.

‘Protestant winds’ would save the day again at Bantry Bay in 1796, which Tone referred to as England’s greatest escape since the events of 1588. Having visited revolutionary Paris and convinced France to aid his cause, Tone is one of a number of individuals detailed in Irish Paris: stories of famous and infamous Irish people in Paris through the centuries. The book documents the engagement of many Irish people, from radicals to writers and even saints, with the city of Paris, doubly romantic for many in Ireland owing to its connections with Wild Geese, figures like Tone and Emmet, and writers like Wilde and Joyce.

Joyce’s Stephen proclaimed non serviam in relation to the pressure of the conforming social forces of the day. Milton’s Ireland: royalism, republicanism, and the question of pluralism investigates Milton’s more direct engagements with Ireland, which were considerable despite never setting foot on the island. Influenced by Spenser’s colonial Faerie Queen and part of Cromwell’s administration, Milton supported Cromwell’s campaign in Ireland, while his anti-monarchist republicanism ironically has continuities in the politics of the United Irishmen and revolutionary-period separatists.

John Montague: a poet’s life is a biography of the modern poet and stalwart of Baggotonia, written by his long-time acquaintance Adrian Frazier. Montague’s work is situated in the context of his wider personal life, from his time in Paris in the upheaval of 1968 to his cross-community work during the Troubles, and features cameos from characters like Patrick Kavanagh, Brendan Behan, Eavan Boland and Bernadette Devlin.

Mike Cronin and Mark Duncan, Revolutionary times—Ireland 1913–1923: the forging of a nation (Merrion Press, €29.99 hb, 432pp, ISBN 9781785374845).

Alan Parkinson and Brian Walker (eds), Ulster 1912–22: change, controversy, and conflict (Ulster Historical Society, €27.90 pb, 286pp, ISBN 9781913993610).

Edward Burke, Ghosts of a family: Ireland’s most infamous unsolved murder, the outbreak of the Civil War and the origins of the modern Troubles (Merrion Press, €20 pb, 314pp, ISBN 9781785375224).

Chris Lawler, Robert Barton: a remarkable revolutionary (The History Press, €20 pb, 204pp, ISBN 9781803998169).

Michael B. Barry, 1588: The Spanish Armada and the 24 ships lost on Ireland’s shores (Andalus Press, €29.99 hb, 288pp, ISBN 9781838485931).

Isadore Ryan, Irish Paris: stories of famous and infamous Irish people in Paris through the centuries (self-published, €22.50 pb, 347pp, ISBN 9781320327787).

Lee Morrissey, Milton’s Ireland: royalism, republicanism, and the question of pluralism (Cambridge University Press, €105.04 hb, 266pp, ISBN 9781009462389).

Adrian Frazier, John Montague: a poet’s life (Lilliput Press, €24.95 hb, 500pp, ISBN 9781843519102).