Irish soldiers, surgeons, revolutionaries and pressmen—as well as at least one downright chancer—all joined in the conflict that saw the downfall of the Second French Empire.

By Isadore Ryan

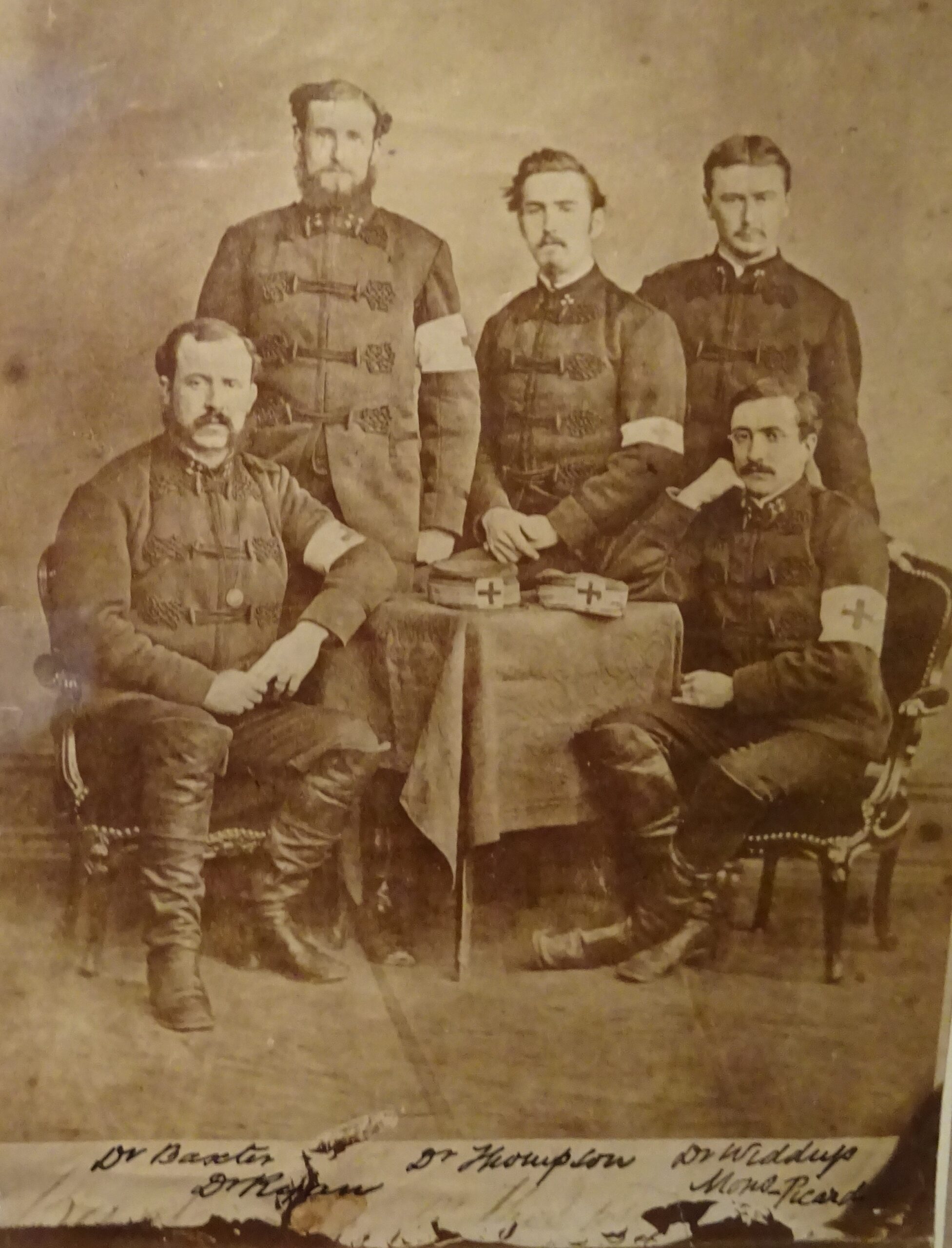

Irish participation in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870–1 took various forms and was overwhelmingly on the side of Ireland’s historical ally, France. The onset of the war in July 1870 triggered various fund-raising efforts and public demonstrations in support of France. Most visibly, an Irish ambulance, led by Charles Baxter, a former surgeon in the British army, was raised through public subscription and arrived in Le Havre on 11 October 1870. It was made up of between 250 and 300 men, three times more than was required to service four ambulance wagons. Consequently, one Martin Waters Kirwan, a former British officer and Fenian sympathiser from Galway, had no trouble finding 100 volunteers among their number to form the Compagnie irlandaise to fight alongside the French.

JAMES DYER MacADARAS’S IRISH BRIGADE

Kirwan’s path soon crossed that of one James Dyer MacAdaras, born in Rathmines in 1838. According to the Irish republican journalist John Devoy, MacAdaras had been eking out a living as an interpreter and guide for American tourists in Paris before he convinced the French military establishment to grant him permission to form an Irish brigade. Appointed as lieutenant-colonel in the second foreign regiment, MacAdaras set up his stall in Normandy in September 1870 with the intention of coordinating the promised London Irish recruits.

The Irish brigade saga proved an unhappy experience for all concerned. The French failed to provide food, arms or pay for the London Irish, who gained a bad reputation because of their rowdiness, and at one stage the British consul had to intervene to feed them. A French war ministry report later summarised MacAdaras’s efforts thus: ‘[He] had promised to bring 6,000 Irishmen to France but only managed to bring 300, who did not perform any service and who were quickly repatriated’. Ex-Foreign Legionnaire James O’Kelly, who was sent to England to find the requisite Irishmen, returned to Paris after the war in 1871 to find that his pay ‘had already been drawn and spent by MacAdaras’, according to Devoy.

COMPAGNIE IRLANDAISE

That left the Compagnie irlandaise under Kirwan, who had quickly determined that MacAdaras was an impostor. The Compagnie was incorporated into the Régiment étranger de marche. After meandering around central France in freezing weather and equipped with shoddy boots, the unit finally saw action in the closing days of the war in January 1871 around the towns of Montbéliard and Besançon, close to the Swiss border, and suffered losses. One of the Compagnie’s many colourful characters was Sergeant Frank Byrne. Kirwan described ‘the famine and fatigue’ that affected Byrne’s appearance and the rest of the unit by the time Montbéliard was reached: ‘For weeks the men had had no opportunity of washing hands nor face … Byrne’s eyes were sunken, his cheeks were hollow, and the cheekbones protruded so as almost to speak “hunger”.’ Byrne was later to be implicated in the 1882 Phoenix Park assassinations, after which he fled again to France where, he claimed, his service in the Compagnie irlandaise ensured that he received favourable treatment from the authorities.

The Compagnie irlandaise contained veterans of the French Foreign Legion such as Frank McAlevey, who had campaigned in Mexico and Africa and was wounded at Montbéliard. In the Foreign Legion itself, with the rank of lieutenant, fought Edmund O’Donovan, who had escaped to Paris after the abortive Fenian rising of 1867. He was wounded near Orléans in December 1870 and captured. Later writing about his experiences, O’Donovan claimed that seventeen other Irishmen joined the Legion at the outbreak of the war and fought with him. After building a solid reputation as a war correspondent, he was killed in the Sudan in 1883.

AMBULANCES

Meanwhile, the Irish ambulance was split into two parts, one based in Evreux and the other sent to the Loire region, scene of bitter fighting. Irish doctors and surgeons also served in the ambulances financed by subscriptions in the US and UK, with Tipperary man Charles Ryan leaving a vivid account of his time with the Anglo-American ambulance. Ryan was present at the decisive battle of Sedan on 1 September 1870, which saw a French army defeated and Emperor Napoleon III captured. On that day alone, his ambulance treated 100 officers and 524 men. Ryan then found himself in Orléans (together with Belfast doctor William McCormack) when it was overrun by the Bavarians on 11 October and was still there when Orléans was briefly relieved by the French a few weeks later.

In Paris, John Patrick Leonard from Cork, long-established stalwart of Irish nationalism in Paris, was heavily involved in coordinating relief from Ireland and America and was later awarded the Légion d’Honneur for his bravery as a medical orderly. Military ambulances were organised at the Irish College (thanks partly to donations from the Irish bishops) and at the main Catholic church for the English-speaking community in Paris, St Joseph’s on Avenue Hoche. The Passionist fathers Bernard O’Loughlin, born in England of Irish parents, and Francis Bamber (who died in Dublin in 1883) were among those present at St Joseph’s, completed only a year before the war broke out. Of a visit to the Irish College in October 1870, Bamber wrote: ‘We found national guards going through their exercises on the grounds, whilst the College itself was converted into a vast ambulance; but of the fathers, we found none: they, as well as the students, had taken flight from Paris’.

The Irish served in other hastily assembled units. The four Casey brothers—Joseph, James, Patrick and Andrew—joined the French ranks. Nationalists all, the brothers were well established in Paris by 1870, where they worked as typesetters. Andrew served as an officer in the Légion des Amis de la France (a corps consisting of about 250 foreigners), was wounded and was decorated for his bravery. Of the others, Joseph appears as ‘Kevin Egan’ in James Joyce’s Ulysses, while Patrick was secretary to the inimitable James Dyer MacAdaras at one stage. The Caseys’ mother is mentioned in Father Bamber’s account of the Prussian siege: ‘She told us she had been that day to the market—halle centrale—for the purpose of getting some provisions, but on seeing a long line of rats hung up for sale her courage failed her, and she went away without purchasing anything’.

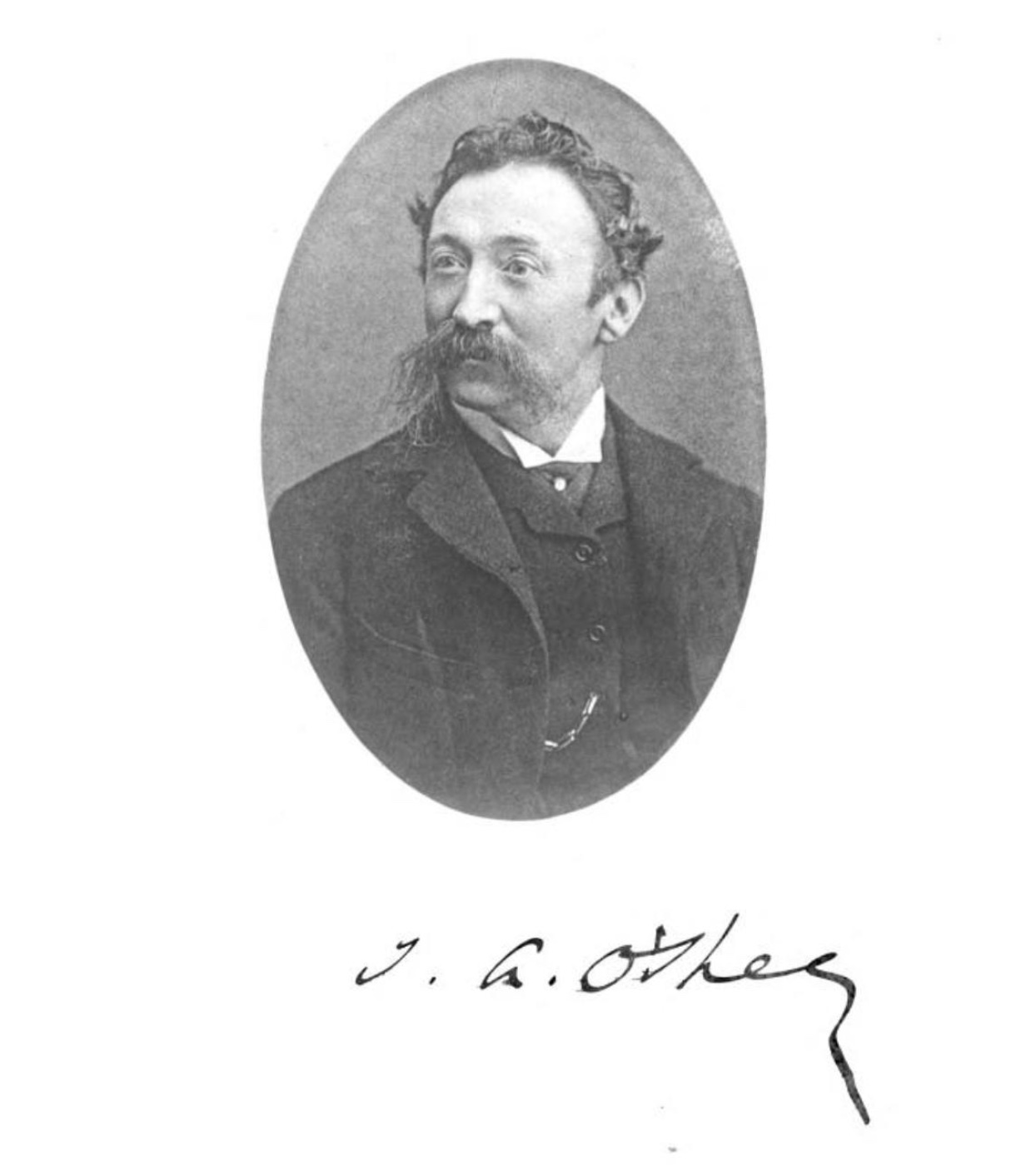

In late October 1870, journalist John Augustus O’Shea learned of the death during the siege of a certain Delany, a member of the Légion des Amis. O’Shea recounts that Delany had felt the urge to join the French because the ruins of a monastery where the Merovingian king Dagobert II (c. 650–79) had been educated were on the grounds of his father’s property in Queen’s County (!). According to O’Shea, another Irish member of the Amis called George Gallaher had set up a canteen at an outpost near the Porte Saint-Ouen but proved too generous in affording credit to customers. Also with the Amis was one Paddy McDermott, described by O’Shea as ‘a good-natured Republican of the Belleville brand’.

People of Irish origin turn up in even more surprising contexts. One Richard O’Reilly Robert was appointed mayor of the 10th Arrondissement by the provisional government during the Paris siege, while the Mayo-born reporter Denis Bingham mentions a ‘Major’ O’Flanagan who had joined one of the foreign ambulances. During one of the attempted break-outs from Paris, ‘great was the surprise of both sides to see the Major … wild with whisky and excitement gallop into the German lines, gesticulating violently and shouting at the top of his voice, “Vive la France”’.

JOURNALISTS

Then there were the journalists. The most famous was undoubtedly Dublin-born William Russell of The Times, who had made a name for himself with his uncompromising reports on the Crimean War. Russell covered the four-month siege of Paris from the German HQ in Versailles. Slightly less well-known was the aforementioned John Augustus O’Shea, correspondent for the London Standard and a regular nineteenth-century daredevil. O’Shea had moved to Paris around the time of the Great Exhibition of 1867 with the idea of studying medicine, having previously fought in the Irish brigade that defended the Papal States in 1860. At the outset of the war he had joined the French forces gathered at Metz, where he was briefly accused of spying. Making his way back to Paris, he elected to stay in the French capital throughout the siege. O’Shea’s closest friend during the siege was another foreign correspondent, Dubliner William O’Donovan (brother of Edmond), who, despite his nationalist politics, was later to become leader writer for the Irish Times. There was also Lewis Strange Wingfield, Lord Powerscourt, described by O’Shea as ‘a universal genius, who could make poetry, plays and pictures’. While serving in the American ambulance, Wingfield also sent reports from the besieged city to London newspapers.

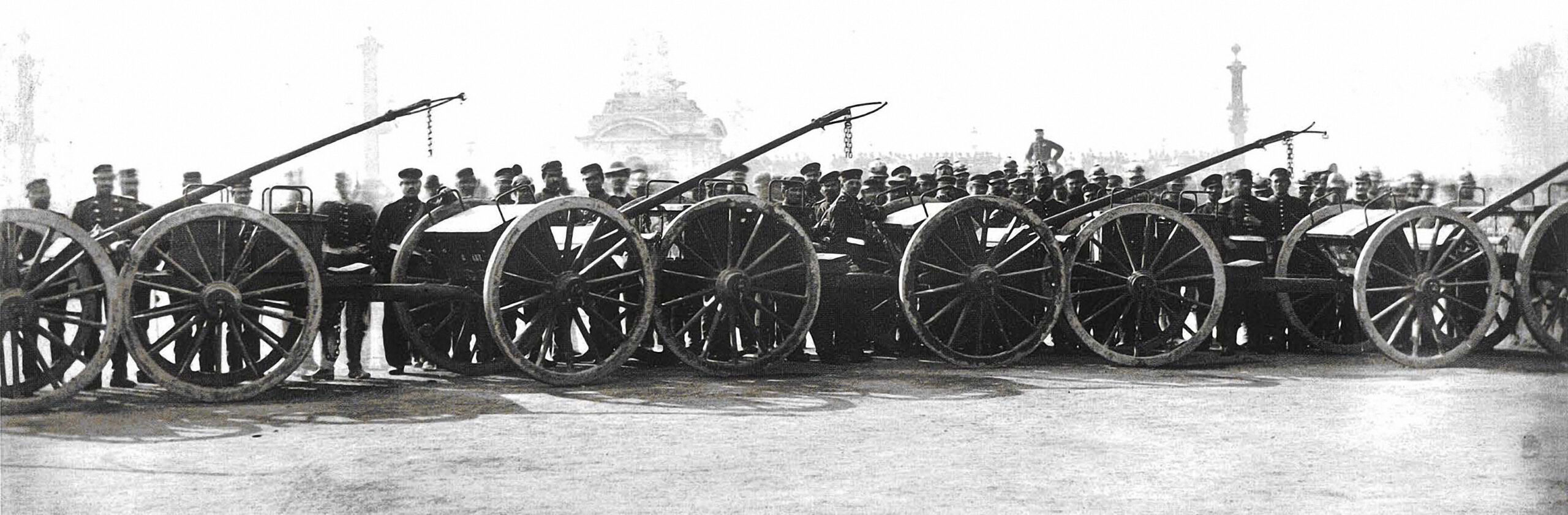

SIEGE OF PARIS

The Prussians brought up siege guns and prepared to bombard Paris in late October 1870, although Russell recorded ‘great doubts in the highest quarters as to the propriety of this step in military and moral sense, and for my own part, I would rather not assist at it’. Inside Paris, O’Shea complained that the early weeks of the siege ‘waxed monotonous … boredom and stupidity were dominant’, although the city seemed ‘positively getting reconciled to its imprisonment and privations’. Horse meat was still to be had. A ‘butcher’s store for the sale of dead asses was opened in the Rue de l’Ancienne Comédie’, wrote O’Shea, and he recorded seeing a soldier on the Avenue de la Grande Armée ‘skinning a cat, preparatory to making giblet soup’.

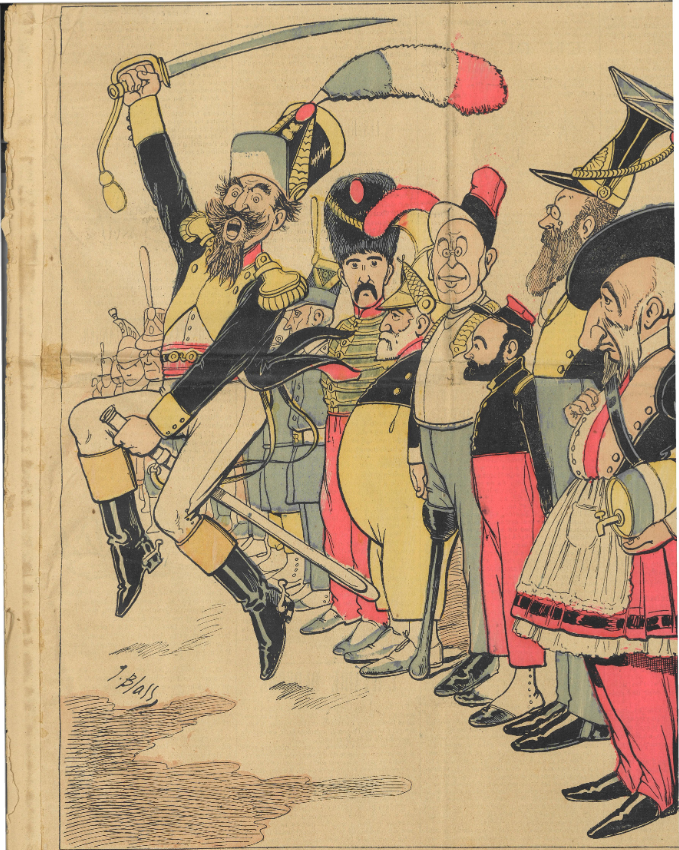

The mood of the populace darkened considerably at the end of October 1870 after another of many unsuccessful break-out attempts and the arrival of news that a 140,000-strong French army besieged in Metz had surrendered. These dual hammer blows led to the storming of the Hôtel de Ville, the seat of the provisional government, and an abortive attempt to set up a commune. Unorganised, the mob was soon dispersed without bloodshed, leaving O’Shea to rue a lost opportunity: ‘A few rounds of canister in October 1870 might have averted the massacres of May 1871’.

The pace of events accelerated in early January 1871, when the Prussians finally started shelling the centre of Paris in earnest. At the same time, the revolutionary clubs, concentrated in the east of the city, were becoming restive again, leading to another unsuccessful attempt to unseat the provisional government. On the cold and drizzly morning of 18 January 1871, Russell was invited to the Galerie des Glaces in Versailles to witness the formal proclamation of Wilhelm I as German emperor. The following day, the French made one final desperate attempt to break the city’s encirclement towards the south-west. On 20 January Russell was back in the Galerie des Glaces, but instead of ceremonial pomp the place was ‘now a valley of lamentations. Rows of little cots, each with a blood-stained tenant, are ranged along the walls.’

PARIS COMMUNE

By this stage, the growing risk that popular protests inside Paris might turn into revolution was enough to persuade both sides to step up peace negotiations. The Prussians stopped shelling Paris on 27 January, with an armistice coming into effect the following evening. Preliminary peace negotiations were concluded on 26 February, with the French agreeing to a triumphal march by the Germans down the Champs Elysées in return for retrieving the town of Belfort from annexation. The parade, witnessed by O’Donovan and O’Shea, took place on 1 March, with the latter writing that amid ‘spirit-stirring note, clash of cymbal and beat of drum … the spectacle was one of the most thrilling I had ever witnessed’. Afterwards, the two Irishmen stopped in the Marignan café at the bottom of the Champs Elysées, where they saw a party of Bavarian officers having a meal: ‘A group of indignant Frenchmen gathered outside, and as soon as the Bavarians left, they proceeded to demolish the windows with volleys of stones’.

Both O’Shea and O’Donovan cast a sceptical eye over the revolutionary commune that took over Paris in March 1871. Given his politics, O’Donovan was probably less severe in his opinions of the commune than the general Irish Times reader of the time. Yet, according to John Devoy, O’Donovan thought that the majority of the communards ‘were not really Communists at heart or by conviction but were unbalanced by the hardships of the Siege’. The commune was crushed by government troops in May 1871. Up to 7,500 people were killed or executed while many public buildings were destroyed, including the Tuileries palace and the Hôtel de Ville, over the course of the so-called semaine sanglante. O’Donovan later became associate editor of the Parnellite United Ireland newspaper. He returned to Paris when the commune was suppressed and died in New York in 1886. John Augustus O’Shea’s career as a foreign correspondent lasted longer. After France and before his death in London in 1905, he covered such events as the famine in Bengal, the Third Carlist War in Spain and various coronations.

Isadore Ryan is a financial editor based in Paris.

Further reading

M.W. Kirwan, La Compagnie irlandaise (1873; Uckfield, 2009).

J.A. O’Shea, An iron-bound city (2 vols) (1886; South Varra, 2016).

C.E. Ryan, With an ambulance during the Franco-German War (1896; Uckfield, 2015).