By Sophie McGurk

Kilmainham Gaol exists in the forefront of Ireland’s mind as the site of execution of seven leaders of the 1916 Rising. It is an institution intrinsically linked with the story of Irish nationalism. Kilmainham Gaol was first built in 1796 and from its conception it was a site of crowded incarceration and public hangings. In the beginning there was no segregation of prisoners—men, women and children shared cells, with sometimes up to five in a cramped, cold cell. The east wing of Kilmainham Gaol (opposite page) opened in 1864 and, while living conditions improved, a new and more sophisticated form of punishment was introduced. The east wing was well received for its panoptic design, which was modelled on Pentonville Prison in London. Pentonville opened in 1842 and was the first to be built according to English philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s plans for the ‘Panopticon’.

BENTHAM’S PANOPTICON

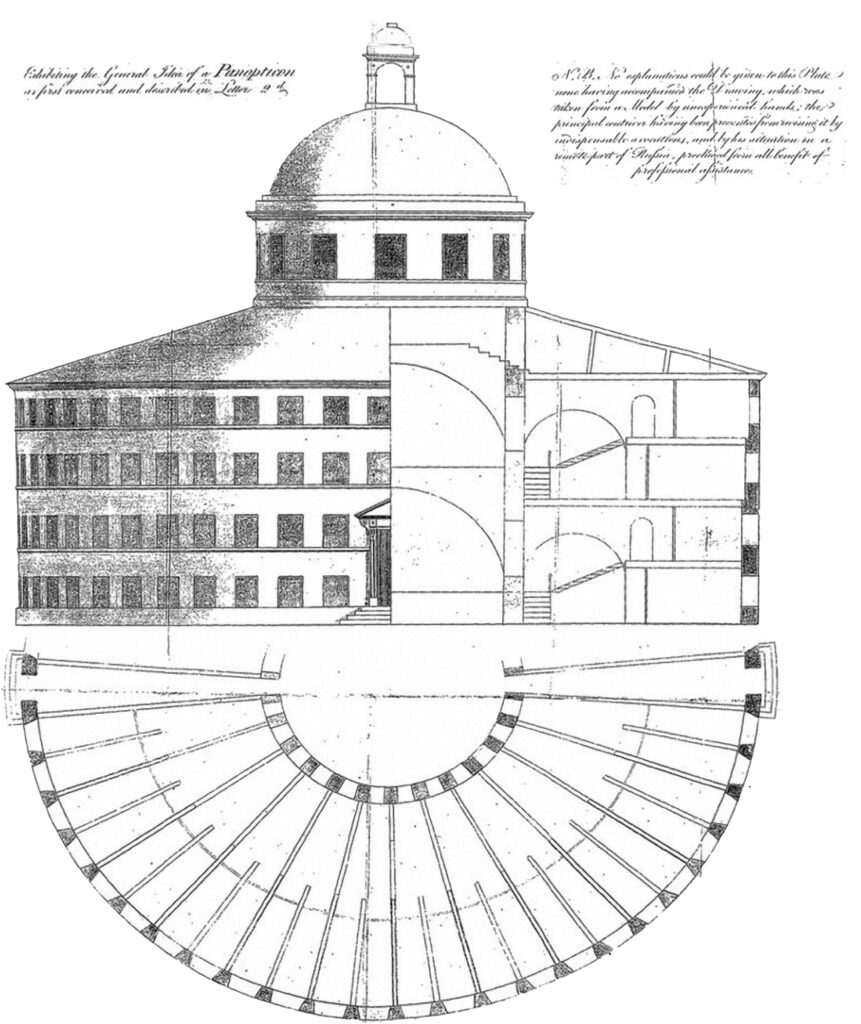

The Panopticon is an architectural innovation that was first seen in Bentham’s eponymous work Panopticon: or, the inspection-house. Containing the idea of a new principle of construction applicable to any sort of establishment, in which persons of any description are to be kept under inspection. And in particular to penitentiary-houses, prisons, houses of industry, work-houses, poor-houses, manufactories, mad-houses, hospitals, and schools and that would result in his being popularly considered the ‘father of surveillance’. Panopticon was first published in 1787 and since then it has acted as a blueprint, both metaphorically and literally, for the modern prison.

The word ‘panopticon’ comes from the Greek word panopticos, meaning ‘all-seeing’. The architectural intention of the Panopticon is exactly that: to be all-seeing. Its basic premise is that of a central tower, with cells making up the circumference. In its guise as a prison, literary theorist Michel Foucault described the Panopticon as

‘an architecture that is no longer built simply to be seen, or to observe the external space, but to permit an internal, articulated and detailed control—to render visible those who are inside it; in more general terms, an architecture that would operate to transform individuals: to act on those it sheltered, to provide a hold on their conduct, to carry the effects of power right to them, to make it possible to know them, to alter them.’

In essence, the Panopticon is as much about psychological as about physical imprisonment.

The east wing of Kilmainham Gaol adhered to Bentham’s design—it was possible to see all 96 cells from a central viewing area. The use of light was also intentionally philosophical; the large skylight of the east wing would work to inspire the prisoners, and their out-of-reach cell windows would, in turn, encourage them to turn heavenward. In fact, we can say that the east wing acted as a very literal manifestation of the Enlightenment. The Enlightenment, both a period and a process, dominated the intellectual and philosophical world between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Historically, many view the Enlightenment as a time of freedom, but it was a type of freedom that was only available to the élite. It was also during this paradoxical time that Bentham was creating his new panoptic model, demonstrating that the products of this type of freedom of expression and thought were often having the inverse effect. The irony of this was not lost on Foucault: ‘The Enlightenment, which discovered the liberties, also invented the disciplines’.

FOUCAULT’S DISCIPLINE AND PUNISH

The construction of Kilmainham Gaol’s east wing and its development from a rudimentary type of prison to the sophisticated design of the Panopticon is directly in keeping with Michel Foucault’s theories on the history of incarceration and state control in his aptly named 1975 work Discipline and punish.

Discipline and punish was indebted to Bentham and relied heavily on his concept of the Panopticon. The work is divided into four parts (‘Torture’, ‘Punishment, ‘Discipline’ and ‘Prison’), and the progression of this history of discipline can be reflected in the biography of Kilmainham Gaol.

‘Torture’ begins with Foucault situating ‘the body’ in the history of crime and punishment. In this section he looks to more representative and psychological forms of punishment. He charts the development of new modes of discipline that move away from explicitly corporal and public forms of punishment, i.e. away from punishment as a ‘spectacle’, which is something we can see in Kilmainham Gaol itself. As mentioned, it was originally a site for public hangings, which were intended to be a public spectacle. This practice declined in Kilmainham as the prison became more about the control and psychological discipline within the walls. The last public execution there was in July 1865.

In ‘Punishment’ Foucault becomes more interested in the ‘representation of the penalty, not its corporeal reality’. Foucault’s power develops so that it can be defined as an imbalanced relationship wherein one person has affect over another’s actions and movements in time and space. If we think about it, that is really what we understand a prison to be.

This idea is further elucidated in his third part, ‘Discipline’, and forms the basis for what we know to be the modern ‘prison’. It is here that Foucault directly engages with Bentham’s Panopticon. The combination of hierarchical observation (made possible by this architectural ingenuity), the control of activity and the monopoly on knowledge creates a distinct power dynamic. The superiority of the Panopticon model and the effect it had on the history of discipline and punishment are wholly recognised and acknowledged by Foucault: ‘The Panopticon is a marvellous machine which, whatever use one may wish to put it to, produces homogeneous effects of power’.

The final part sees Foucault sum up how the development and innovations of the prison have infiltrated our wider society, resulting in its becoming one ‘carceral system’. The prison is just one of the many institutions (the school, the factory, the hospital etc.) that are completely integrated and ingrained into our everyday lives.

In Discipline and punish, Foucault provides a breakdown of the explicit use of the Panopticon as a prison: ‘All that is needed, then, is to place a supervisor in a central tower and to shut up in each cell a madman, a patient, a condemned man, a worker, or a schoolboy’. He describes the cells as being like ‘so many cages, so many small theatres, in which each actor is alone, perfectly individualised and constantly visible’. However, and this is vital to the purpose of the design of the Panopticon, this visibility does not go both ways. The list of ‘inmates’ that could be put in these literal or metaphorical cells may be surprising, but in fact Bentham did not intend for the Panopticon to be used solely for prisons; rather it was to be applicable to any or all ‘institutions’. Foucault asks of his readers: ‘Is it surprising that prisons resemble factories, schools, barracks, hospitals, which all resemble prisons?’ These institutions may appear to vary greatly in function but in fact they have in common the way that their architecture can control the population within. This is exactly what is seen with the intention, design and architecture of the east wing of Kilmainham Gaol.

Thus the Panopticon’s ‘unverifiable nature’ is the root of its power and control. The main effect is succinctly summed up by Foucault: ‘He is seen but he does not see; he is the object of information, never a subject in communication’. The inmate can never know whether he is currently being watched and thus must constantly act as if he were, producing ‘a state of consciousness and permanent visibility [that] assures the automatic functioning of power’. So whereas a prison is a physical form of incarceration and punishment, the Panopticon introduces a new, psychological element. It is, as Bentham said, much more than architectural ingenuity: it is an event of the human mind.

ORWELLIAN ‘ALL-SEEING EYE’

There is an eye-shaped hole on the interior of the cell doors (above/below), giving the effect of an Orwellian ‘all-seeing eye’. The very choice to inlay an eye shape into the door underlines the psychological punishment of constant surveillance and is reflective of the core purpose of the Panopticon: observation. On the exterior of the door the cover can be left on a latch, whereby the prisoners can be watched without knowing whether they are being watched. In addition to the symbolic eye, the walkways were lined with carpets, targeting (or removing) another sense, as inmates could not hear approaching guards.

The executed rebels of the 1916 Rising were not held in the east wing of Kilmainham Gaol but in the older, harsher conditions of the west. Nonetheless, a link can still be forged between the colonial ‘discipline and punish’ following the Rising and this discussion. And Roger Casement was not executed in Kilmainham Gaol like the other leaders of the Rising but in Pentonville Prison—the very prison from which Kilmainham Gaol took its inspiration, and the prison that was the first iteration of Bentham’s Panopticon.

Sophie McGurk is a Ph.D student in the Department of Classics, Trinity College, Dublin.

Further reading

J. Bentham, Panopticon: or, the inspection-house (Dublin, 1787).

M. Foucault, Discipline and punish: the birth of the prison (Paris, 1975).