By Billy Shortall

Although invited, the Irish Free State refused to participate in the British Empire Exhibition, which took place between April and October 1924. It also declined to participate when the exhibition was extended for a second season in 1925. Why not?

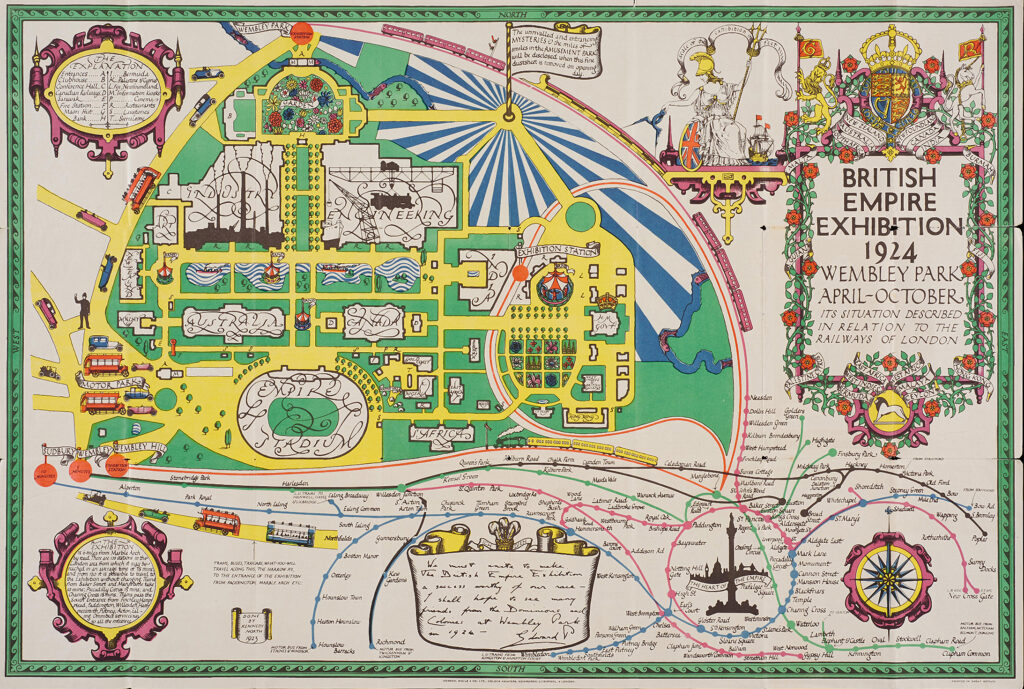

The event took place on a 220-acre site at Wembley, London. It held the promise of stimulating and improving trade among the participating nations; 25 million anticipated visitors could view the participating dominions and colonies of the empire in one location. The stated aim of this event was to ‘ensure the empire’s stability after World War I’ and to improve its economy. All 58 territories that composed the British Empire at the time were invited to participate with commercial and artistic national displays. However, despite no official involvement there was an Irish presence.

‘ABSTENTION NEITHER GOOD POLITICS NOR GOOD BUSINESS’

The invitation letter stated that participation ‘would produce an excellent impression over here … [and] would probably be of material assistance to the Free State in advertising their economic resources and industries’. The Irish high commissioner in London, James MacNeill, wrote a memorandum outlining the advantages of taking part, stressing that the state had been offered a good exhibition site and that there were benefits in promoting trade, commerce and the new state itself, adding that ‘abstention seems to be neither good politics nor good business’. The only argument against participation that MacNeill offered was that ‘the name of the exhibition does not attract’. MacNeill’s report was circulated to the Executive Council of the government, who confirmed their provisional approval to participate, subject to suitable accommodation for an exhibit. Exhibits suggested for display at the event included stained glass, carpets, embroidery, lace, enamels, homespuns and pictures by Irish artists, as well as educational, industrial and tourism displays.

Just over two weeks later, on 27 February, the Executive Council rescinded their decision to participate, citing the need to reduce expenditure. MacNeill wrote to Minister for Finance Ernest Blythe, supporting Irish engagement in the exhibition and suggesting that participation would be financially positive. To salvage Irish participation, event organisers offered a variety of cheaper options, including a smaller pavilion site or space in the exhibition buildings that would remove the need to build a venue. Further discussions between the Irish office of the High Commission in London and various departments took place during the year.

The departmental secretary for industry and commerce, Gordon Campbell, wrote to the Executive Council in December 1923 on behalf of the minister, arguing that it would be a mistake to risk ‘non-appearance at the Exhibition’ and ‘prejudice Irish trade’. The memo bluntly states that ‘the question [of participation], however, appears to this Ministry largely a political one’. The Executive Council revisited their decision on several occasions, finally noting that ‘the Executive Council have decided that the Irish Free State will not take part in the British Empire Exhibition. They consider that the money would be better expended on an Exhibition here during the national Tailteann Games.’ Concentrating efforts on that year’s games, Tailteann director J.J. Walsh arranged for the distribution of Tailteann advertising literature at the Empire Exhibition.

PROMOTING THE BRITISH EMPIRE

Despite the likelihood of increased trade, the possibility of ‘build[ing] popular support for British imperial policies’ and the country’s place within the same was too high a price. The Irish newspapers backed the initial decision to take part—‘it is gratifying to know that all Ireland will be represented’—and saw the retraction as ‘a matter for general regret’. Non-participation was regarded as a missed opportunity to advertise the Free State and push its industries, ‘find new markets for its agricultural produce’ and establish the ‘tourist industry on a sound basis’. Exhibiting the Free State would give visible evidence of its ‘existence’ and ‘stability’ after a period of revolution and violence, and provide an ‘effective cure’ for the country’s ‘insularity of outlook’.

Members of Seanad Éireann also saw advantage in being part of the exhibition, with Oliver Gogarty noting that other ‘Colonial Premiers have seized upon the sites in Wembley’; he claimed that if New Zealand and Australia saw trading opportunities, the Free State had greater opportunity because of its closer proximity to Britain. In the same debate W.B. Yeats said that [Irish] artists had received invitations to exhibit their work and he feared that they would have to exhibit in the ‘general mass of English artists’, causing confusion as to the position of the Irish Free State. A separate Irish room would, he believed, create ‘a distinct possibility for Ireland’. Individuals recognised that the exhibition offered the country trade and soft power opportunities, but it was primarily about promoting the British Empire. The Free State sought not to internationally declare, tacitly or otherwise, its allegiance to the empire but rather to reaffirm a political and cultural separation from England through non-participation.

There was a large Ulster exhibit in the Palace of Industries of the United Kingdom, which served to highlight the North/South divide and the six counties’ loyalty to the monarch. When James MacNeill had advocated participation, he held out the possibility of doing so in conjunction with Northern Ireland. Despite no official state participation, some Irish companies and visual artists took part independently in the event. The Horace Plunkett Association organised a conference on agricultural co-operation involving English, Irish, Welsh and Scottish participants. The Great Southern & Western & Midlands Railway Companies (Ireland), the City of Cork Steam Packet Co., Jacob’s Biscuits and Jameson Whiskey were among those who exhibited in the United Kingdom industries section.

IRISH ARTISTS WHO TOOK PART

Free State artists who took part independently in 1924 included John Lavery, who also represented Ireland in the 1924 Paris Olympics art competition, and Dermod O’Brien, president of the Royal Hibernian Academy, who exhibited a portrait of the playwright Lennox Robinson. The Youghal Lace Industry showed pieces in the embroidery section, and a trio of artists from An Túr Gloine, Sarah Purser, Wilhelmina Geddes and Ethel Rhind, collaborated on a stained-glass window, St Brendan the Voyager. An Túr Gloine was short of work at this time and the Empire Exhibition offered opportunity for a sale and, more importantly, a means to promote and advertise the co-operative.

The Irish government was approached to participate in the exhibition’s second year and again the Executive Council declined, this time stating that there was a lack of interest expressed by Irish industrial and art industries in participating. Many of the same Irish artists who exhibited in 1924 did show again the following year but there were fewer works. One noteworthy exhibit featured the ‘Great Seal of the Irish Free State’ and two related seals, credited in the catalogue to Cecil Thomas of the London Royal Mint, where it was cut. The entry makes no reference to their Irish designer, Archibald McGoogan (1860–1931). The seals featured the harp surrounded by Celtic Revivalist ornament appropriated from the base of the ‘famed’ Ardagh Chalice, ‘accepted as representing the crowning point of ancient Irish art in decorative metal work’, and the name of the ministry and the title ‘Saorstat Éireann’. Exhibiting the seals in the British section at the exhibition without acknowledging their Irish designer could have led some, particularly the British public, at this 1924 exhibition to the misconception that the seals—and by extension the Irish Free State—were still part of the United Kingdom.

Free State exhibitors were intermingled with British companies in the Palace of Industry, which was dedicated to British industries, whilst Northern Ireland (described as ‘Ulster’) industries exhibited in their own section. Similarly, Irish artists were included in the British sections in the Palace of Arts. British and Irish exhibits were inextricably linked, giving the impression of a close union rather than the separation that the Free State intended to assert regarding the ‘political question’ by non-engagement.

OTHER DOMINIONS

Other dominion participants, such as Canada, South Africa and Australia, used the British Empire Exhibition ‘to present a distinct national identity in pursuit of greater autonomy from Britain’ through their enthusiastically reviewed artistic and industrial exhibits. Conversely, Irish absenteeism resulted in a lack of government control and agency over Irish identity, as exampled by losing the significance of the seal, a dominant and potent icon of the new Irish Free State. Official non-participation and the inclusion of participating Irish artists in the rooms reserved for British painting confirmed W.B. Yeats’s fears, as expressed in the Seanad debate, and led to confusion about the position of the Irish Free State.

This was a lesson that the Irish Free State learned, and it actively engaged with British and other international exhibitions and trade endeavours in the following years, such as the Empire Marketing Board from 1926 to 1933, the ‘Exhibition of Paintings, Drawings, Engravings and [small] sculpture by artists resident in Great Britain and the Dominions’ between 1927 and 1931, and the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933, and it took a prominent role in the Empire Exhibition held in Glasgow in 1938. The Executive Council of the Free State discussed and approved participation in these events, but insisted on asserting its identity and how it was represented, clearly identifying as Irish and not British. The revolution was over and Irish art would play an ocular role in the reconciliation of Irish identity, asserting uniqueness and compatibility in international arenas.

Billy Shortall is a research fellow in the School of Histories and Humanities, Trinity College, Dublin.

Further reading

A. Davis, ‘The Wembley controversy in Canadian art’, Canadian Historical Review 54 (1) (1973).

J.E. Findling & K.D. Pelle (eds), Encyclopaedia of World’s Fairs and Expositions (London, 2008).

The British Empire [Art] Exhibition (1924), Palace of Arts (London, 1924).