By Tarlach de Blácam

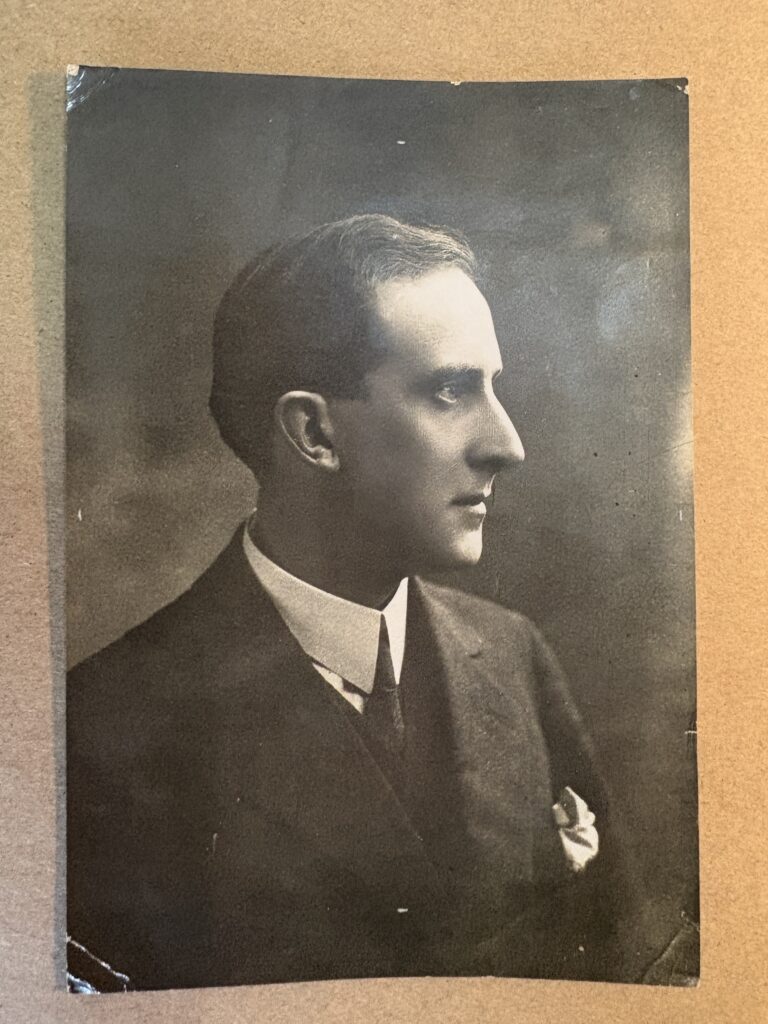

Aodh de Blácam (Harold Saunders Blackham), journalist, essayist, poet and novelist, was born in London to a Newry-born apothecary, William George Blackham, and his English wife, Elizabeth Evison Saunders. According to Aodh’s uncle, Major-General Robert James Blackham, he ‘was a member of a family which claims descent from Sir Charles Blackham, Baronet, a London merchant whose nephew was ADC to William of Orange, settled in Newry and established an Irish branch’. In the nineteenth century the Blackhams carried on a clock-making business in Newry.

In 1907 his father died, aged 47, when Aodh was just fifteen years old. An only child, he was brought to live with his maternal grandfather, Thomas Saunders, a fundamentalist evangelical Protestant, in Muswell Hill, London—an unhappy place for Aodh, whose father, a Methodist, abhorred sectarianism and was on good terms with his Catholic neighbours and the local Irish community in north London.

INTELLECTUAL FORMATION

Outside school, Aodh studied the classics under one Peter Joyce, an elderly emigrant from Ireland with Fenian connections, who possessed a large library and allowed Aodh access to it. Joyce was the fictional character who appeared in Aodh’s first novel, Holy Romans, published in 1920, and also in a short story published in The Irishman in 1913, ‘The Visionary’. Aodh became active in the London branch of the Gaelic League, learning Irish from essayist Robert Lynd (the Belfast-born son of a Presbyterian minister) and novelist Pádraig Ó Conaire, and debating with historian P.S. O’Hegarty and a young Michael Collins.

An ascetically dedicated autodidact and natural intellectual, Aodh studied relentlessly and read voraciously, as evidenced in his essays on literature, philosophy, religion and politics. The fruits of his classical formation were exhibited early in his journalistic career. In February 1913 he reviewed Henry Frowde’s Book of Latin verse under the heading ‘Celt and Latin’ in Arthur Griffith’s newspaper, Sinn Féin. ‘Gaelicism must be fertilized by foreign ideas’, he wrote; ‘if we could temper the luxuriance of folktales with Roman austerity, if we could wed Tara and Athens, we might again realize the Island of the Scholars, if not of the Saints’.

CATHOLICISM AND SOCIALISM

Aodh started on the road of conversion to Catholicism in 1910 and was particularly influenced by the theological writings of Cardinal John Henry Newman, as well as by the contemporary English Catholic publicists G.K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc. Influenced by Robert Lynd, Aodh became a strong advocate of socialism, as well as supporting the cause of Irish independence from Britain, from an early age.

His diary contains details of a conference in London in January 1914 of Ulster Protestant supporters of Home Rule in the home of nationalist historian and activist Alice Stopford Green. He writes that he was ‘the boy of the party, and too shy to say much’. Among others, the conference was attended by Robert Lynd, Francis Joseph Bigger and Roger Casement. Aodh suggested a solution involving a ‘dual monarchy’ to reconcile unionists. Casement, ‘who had tried to get Redmond to meet Carson and come to some agreement, independently of England’, and was unsuccessful, dismissed Aodh’s idea, saying that ‘too much history had flowed. War was the only solution.’

MARRIAGE

Aodh moved to Ireland in 1914 and married Mary (Máire) McCarvill in 1915 after converting to Catholicism. The McCarvills were small tenant farmers from County Monaghan. They had a history of Fenian activity in the Monaghan/Armagh area. Máire’s father, John, spent time in Armagh jail for his activities. Her brothers Paddy and Johnny became very active later in the War of Independence.

The couple settled first in Enniscorthy, and Aodh began work for the Enniscorthy Echo. After several trips to the Donegal Gaeltacht, he became a regular contributor in Irish to The Irishman, edited by Herbert Moore Pim, close associate of Sinn Féin party founder Arthur Griffith.

Before leaving London, Aodh had written several articles for Griffith’s Sinn Féin newspaper on literature, nationality, politics and some book reviews, initially signed Arald de Blácam, including radical articles under the name ‘Seaghan Ultach’. From his arrival in Ireland in 1914 he wrote for regular publications like the Enniscorthy Echo and the Sunday Independent, and for more radical publications: Sinn Féin, The Irishman, An Saoghal Gaedhealach and New Ireland/Éire Nua. The Sunday Independent articles were mainly essays and book reviews of old and new writings, under the banner ‘Literary Notes and Notions’. This column continued weekly until 1930.

WHAT KIND OF IRELAND?

Aodh and Máire moved to a house in Cill Ulta near Falcarragh in the Donegal Gaeltacht in 1917. There he perfected his Irish and published a book of poetry in Irish in 1918, Dornán Dán (‘A fistful of poems’). Under the influence of thinkers like Chesterton, Belloc and Oswald Spengler, Aodh’s political ideas matured after 1916. He published widely on the kind of state to which he thought the revolutionary movement should aspire, in ideas similar to those expounded by Darrell Figgis and AE (George Russell) around this time. In March 1919 he launched a new publication, The Irish Commonwealth—A Monthly Review of Social Affairs, Politics and Literature, which he edited himself.

Also in early 1919 he published a manifesto, Towards the Republic, followed by What Sinn Féin stands for in 1921. Heavily influenced by Alice Stopford Green, both books emphasise the historical structure of Gaelic civilisation as providing a framework for the development of a culturally autochthonous modern Irish state. Notably, Horace Plunkett’s Irish Cooperative Organisation Society was offered as a model for the development of the mainly rural society that existed in Ireland in 1919. Aodh also consistently expressed admiration for the political perspectives advanced by the socialist intellectual and revolutionary James Connolly. He devoted significant intellectual energy to synthesising Connolly’s emphasis on social equality with the core tenets of revolutionary Irish nationalism and contemporary Catholic social ideals.

Distributism, not socialism, was to become Aodh’s socio-economic prescription for the new independent Ireland, which he expounded on in much more detail in three articles entitled ‘The Foundations of Freedom’ in the periodical Banba (first edition, May 1921). In Donegal, Aodh observed the operation of the Templecrone Cooperative Agricultural Society Ltd, which had been established in 1906 by a small group of local people led by a pioneering leader, Paddy ‘the Cope’ Gallagher. It became an extremely successful business in west Donegal. It was a local shining light for Aodh in his vision for a revitalised rural Ireland where distributism was being implemented.

Aodh was unaware of his uncle Col. Robert J. Blackham’s posting to Dublin in 1920 as Assistant Director Medical Services (ADMS) to British forces, and consequently a target for assassination by his brothers-in-law and their comrades if by chance he were seen and recognised in Dublin in 1920–1. He only made contact with Col. Blackham in 1925 when he received a reply to his request for some Blackham family history. Col. R.J. replied: ‘I am assuming you are the son of my brother William George of Holloway’. Aodh established a warm and friendly relationship with his uncle from then on, and they were in regular contact until they both died in January 1951.

CIVIL WAR

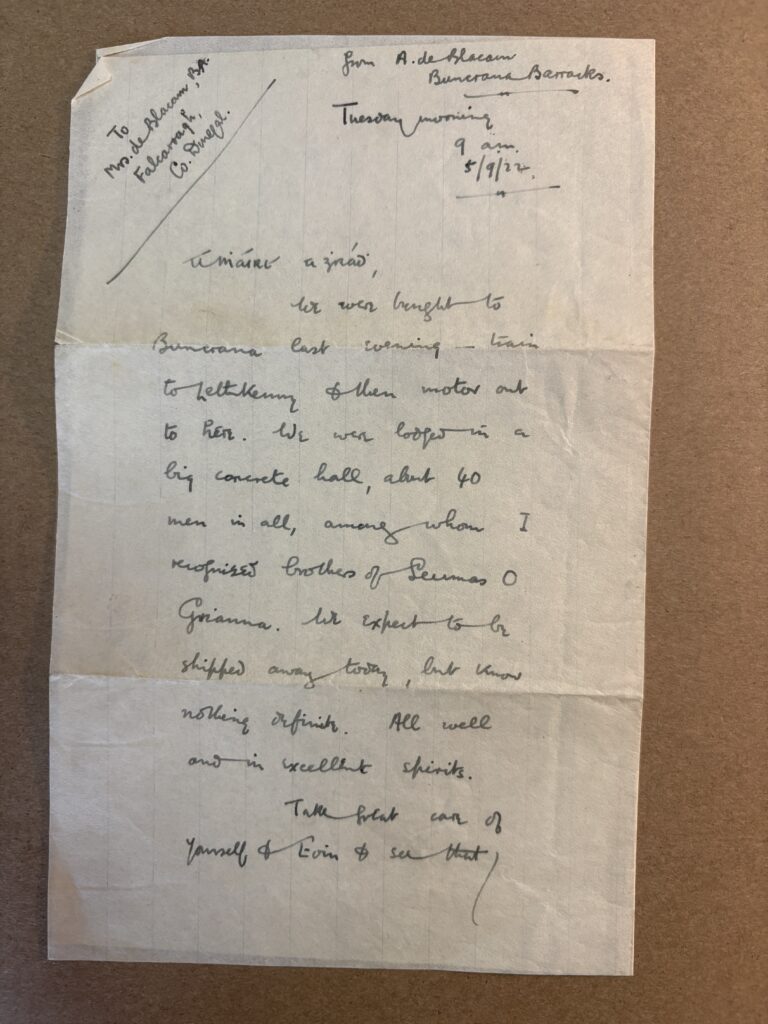

Aodh was interned as part of a general round-up of anti-Treatyites in Donegal in September 1922. His offence was his active role in anti-Treaty publicity. He was not active in military affairs or campaigns.

In spite of his anti-Treaty position, in 1924 Aodh joined the staff of the Irish Times under its staunch unionist editor John E. Healy, where he wrote leading articles and book reviews. He had enormous respect for Healy, though their political attitudes were poles apart. In 1929 he published his most important work of literary criticism. The result of years of research and study, Gaelic literature surveyed received widespread critical praise, including from the Times Literary Supplement and The Spectator.

HISTORICAL NOVELS AND PLAYS

In 1935 Aodh published a historical novel, The lady of the cromlech (selected as book of the month in the US), followed by A life of Wolfe Tone in the same year. He wrote several plays on historical themes. His King Dan (on Daniel O’Connell) was produced in the Gaiety Theatre in 1944. Other plays include Sarsfield is the man and The golden priest (on St Oliver Plunkett).

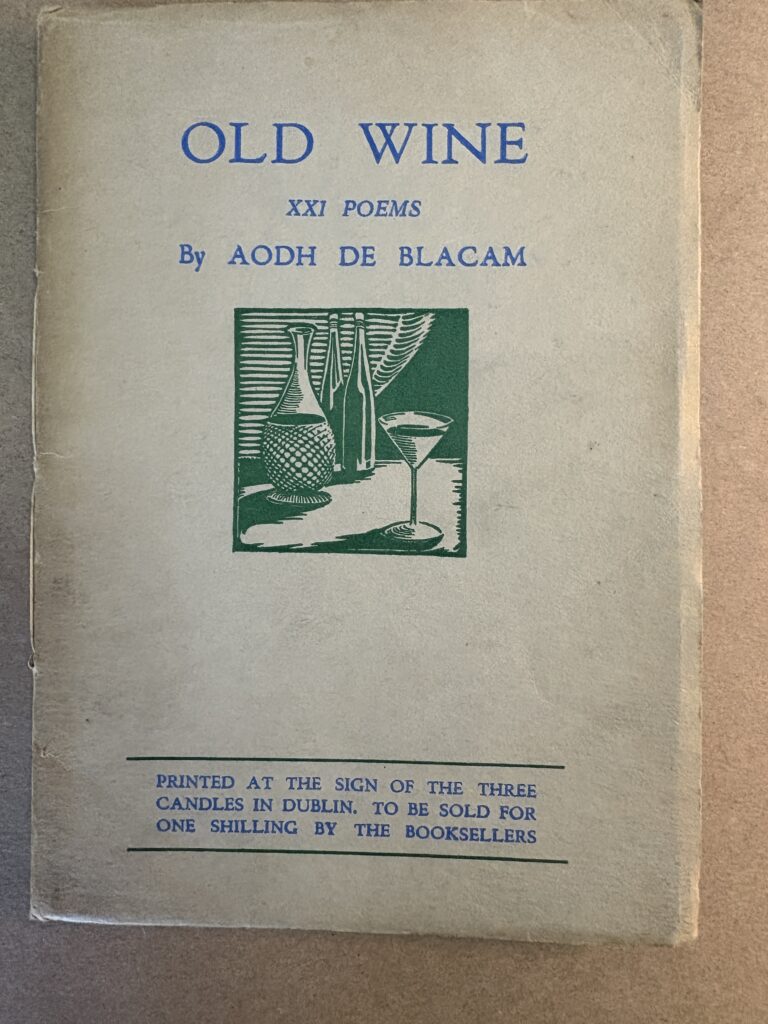

In 1930 he published another small book of poetry, Old wine, with verses in Irish, Spanish and Latin, written chiefly in Irish metrics. In 1931 he joined the staff of de Valera’s newly launched Irish Press, where he wrote a daily column for seventeen years under the pseudonym ‘Roddy the Rover’. This column made him a household name throughout the country, offering a mix of local history and lore with serious comment on public affairs, national and international. He also contributed regular features, essays and reviews under his own name in the Irish Press throughout the period.

SUPPORT FOR FRANCO

Aodh fell out with many of his old friends and colleagues in 1936 when he supported the nationalist side in the Spanish Civil War. He was criticised widely in the left-wing press, where his writings in 1919 and 1920 were held up to illustrate his apparent volte-face. For his part, a recent convert to Catholicism, he saw the war as a conflict between Christianity and a new ‘godless’ Spanish Republic which was intent on supressing the Church. He was misinformed about or blind to the mass executions and atrocities carried out by Franco’s forces. He only made reference to the execution of Catholic priests, monks and nuns.

The story of de Blácam’s 1947 break with Fianna Fáil and his sacking from the Irish Press began with the abandonment of the 1932 policy of self-sufficiency. According to his diary, he agitated throughout 1946 at the Fianna Fáil Executive for an examination of rural policy. In autumn 1946 he put down a motion on the subject of rural depopulation and emigration. It was read on 2 December 1946 at a meeting, with Éamon de Valera presiding. Aodh recalls that ‘there was a field day on the FF Executive … where he was rebuked’.

In late 1947 he felt compelled to resign from the Fianna Fáil executive. In December of that year he explained his decision:

‘For 10 years I have striven to rouse attention to the unnatural scale of emigration threatening the very roots of Ireland. For the last two years I have toiled to bring before the executive those measures which the country dwellers know to be urgently needed to save the countryside. I met indifference and even opposition.’

Immediately after resigning, he joined Clann na Poblachta and ran as a candidate for Louth in the 1948 election, where he received only 1,348 votes. He was frequently denounced by Fianna Fáil ministers and spokespersons in the campaign, who labelled him a ‘Communist’—a defamatory claim, given the era’s prevalent witch-hunts against left-wing advocates. He sent a telegram to de Valera during the election demanding a retraction of this smear, but his request was ignored.

In the period between late 1947 and early 1948, his relationship with William Sweetman, the editor of the Irish Press, deteriorated. He was reprimanded for participating in a radio broadcast ‘violating Irish Press copyright’. In June 1948 his column was reduced to three days a week at half-pay, and shortly afterwards he received notice that it would be discontinued the following month. He expressed his grievances in a letter to the editor and the board, pointing out unfair treatment and meagre compensation compared with remuneration on other Dublin dailies. He claimed that he was left in difficult financial straits after dedicating his best years to writing daily articles for a popular column that had significantly boosted the newspaper’s circulation.

NOËL BROWNE’S HEAD OF PUBLICITY

Shortly after his departure from the Irish Press, Aodh took a position with the Department of Health at the Custom House, working under the new minister, Noël Browne, as head of publicity. In this role he wrote to Archbishop McQuaid to solicit support for the Department’s controversial Mother and Child Scheme, a policy framework intended to provide free health care for mothers and children up to the age of sixteen, regardless of income. The initiative faced intense criticism from the medical establishment and the Catholic Church, who viewed it as an overreach of state involvement in personal health care and family life. Notably, the Irish Times medical correspondent on 25 November 1949 labelled the scheme as ‘state medicine’ and denounced it as a ‘socialistic measure’ purportedly influenced by British and Soviet models. Among the numerous arguments against the scheme, the Irish Times correspondent wrote that ‘exponents of Christian doctrine can show that the principle is contrary to the moral law’. The article concluded with the offensive suggestion that the ‘Custom House [Department of Health] … looks to the Kremlin’.

DEATH

Aodh de Blácam was only 59 when he suffered a heart attack and died in January 1951. A prolific scholar and publisher throughout his life, his literary output, alongside his daily newspaper columns, was substantial. His long-term colleague in the Irish Press, M.J. McManus, wrote of him:

‘Of the men and women with whom I have had an intimate acquaintance none had such a varied or striking array of talents as Aodh de Blácam. He was historian, novelist, playwright and poet … As a journalist he was the most versatile I have ever known and the most industrious. Only the most fluent of pens could have achieved his output which at times was breath-taking.’

Tarlach de Blácam is a grandson of Aodh de Blácam, whose archive was bequeathed to him sixteen years ago. He lives and works on Inis Meáin in the Aran Islands.

Further reading

A. de Blácam, Gaelic literature surveyed (Dublin, 1929 & 1973 with an additional chapter by E. Ó hAnluain).

A. de Blácam, The ship that sailed too soon and other stories (Dublin & London, 1919).

A. de Blácam, What Sinn Féin stands for (Dublin, 1921).

A. de Blácam, The Black North (Dublin, 1942).