National Museum of Ireland, Collins Barracks

By Donal Fallon

Photography is having a moment at the National Museum of Ireland, Collins Barracks, with two very different exhibitions drawing visitors in. A New Form of Beauty draws from the research of Garry O’Neill, author of the cult classic Where Were You?, a social history examination of Dublin youth culture and street style. That exhibition is a visual feast of recent decades, showing Cureheads, ravers and punk rockers on the streets of the capital.

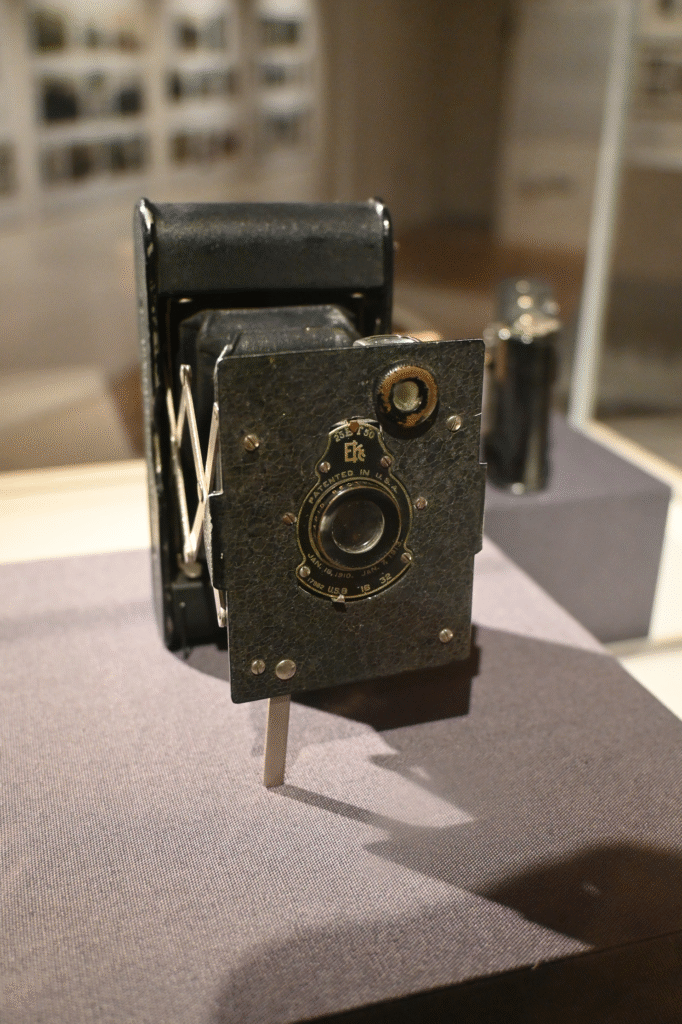

Elsewhere in the museum, the brilliant Imaging Conflict: Photographs from Revolutionary Era Ireland 1913–1923 continues. In a room of few artefacts, one thing we do see is a humble Pocket Kodak camera, which we learn ‘was launched in 1915 as a mass-produced, compact and lightweight camera. Costing £1.10s (about €100 today) it was also affordable.’ If the young faces in Garry O’Neill’s exhibition were well used to posing for cameras by the 1980s, this revolutionary-era exhibition is instead a reminder of how new and truly transformative ‘people’s photography’ was against the backdrop of revolutionary Ireland.

The Irish revolution recalls instantly the name of celebrated photographers like W.D. Hogan and Joseph Cashman, who captured key moments in the period examined here. In a sense, we pass a nod to Cashman’s work on O’Connell Street without realising it, as his 1923 image of the returning trade unionist James Larkin inspired the pose of Oisín Kelly’s monument. While Hogan’s work features in Imaging Conflict, this exhibition is primarily concerned not with the work of landmark photographers but with lesser-explored dimensions of this tale: the camera as a surveillance tool, the connection between photography and propaganda, and the manner in which the camera became a documentary tool for participants in the period.

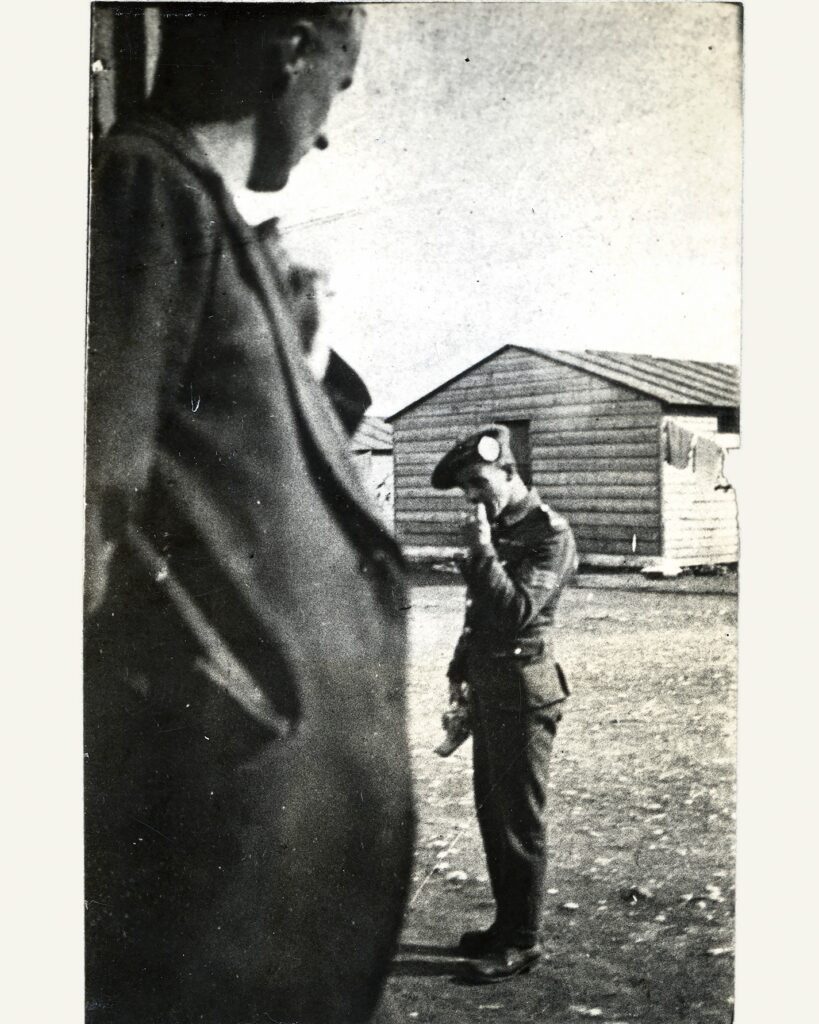

Surveillance and intelligence photography immediately brings to mind state actors, but this exhibition presents images to the public which in some cases have not been on view before. We learn that imprisoned republicans availed of the opportunities presented by new, more discreet cameras, which ‘could be easily concealed under clothing, allowing secret photographs to be taken of guards, which were then smuggled out of the camps to the IRA to identify guards as targets’. These images are intriguing, being naturally unposed and taken from peculiar angles. An image by Joseph Lawless shows the Rath internment camp on the Curragh in 1920, the subject completely unaware.

When interviewed by the Bureau of Military History, protagonists in the revolution spoke on occasion of the importance of photography in the era. A photographer capturing the ‘victory parade’ on the streets of Dublin in the aftermath of the First World War, where Union flags were commonplace on the street, was confronted by republicans who confiscated his film. In Imaging Conflict we see the manner in which both sides created propaganda photography, such as the fictitious ‘Battle of Tralee’, photographed on Vico Road in Dalkey in 1920.

A small gripe with the exhibition concerns its subtitle, emphasising revolutionary-era Ireland. It quickly becomes apparent to the visitor that the battlefields far from revolutionary Ireland are just as significant to the narrative. The Pocket Kodak camera may have offered opportunities to interned republicans in Ireland, but it also provided a means of communication to soldiers fighting in the First World War, ‘proving hugely popular with soldiers of all ranks at war in Europe’. Against the backdrop of wartime censorship and efforts to maintain public morale, we learn that ‘photography on the Front, other than official war photography, was banned by the British War Office in April 1919, making possession of this camera a court martial offence’. Today, the horror of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the ongoing slaughter in Gaza are events daily captured on the cameras we now carry in our pockets. Undoubtedly, fear of the horror of war shaking public sentiment drove the ban on such cameras in 1919.

Almost all the photographs presented in this exhibition, to the surprise of the visitor, are reproductions of originals held in the collections of the National Museum of Ireland. Having undergone ‘a post-production process which aims to keep their original qualities’, everything from signs of wear and tear to original colour tones survives, and the original primary source material is held within drawers behind protective glass.

The widespread availability of photography as a medium shaped the ephemeral legacy of the Irish revolution, as is clear from the wide variety of commemorative posters, postcards, memorial cards and badges produced during the period. By 1916 Dublin was home to some 23 photographic studios, offering portraits that were relatively inexpensive. The exhibition notes that organisations like the Irish Volunteers ‘legitimised their existence as armed forces through the adoption of official photography of members and groups’. One wonders how many of those who posed in studios like Lafayette in their military uniforms had any sense that these images could later become synonymous with martyrdom, appearing in popular commemorative postcards after the Easter Rising.

Content warnings are becoming increasingly familiar in our museum exhibitions, and are justified here in alerting the visitor to particularly macabre images of the dead. In open coffins, we see the charred remains of Patrick and Harry Loughnane, tortured and killed following their arrests in Galway in the winter of 1920. Images of mourners presenting their burnt and mutilated remains before photographers are still shocking, with one particular visitor to the exhibition clearly moved by the photographs during my visit.

Imaging Conflict’s extended run at the National Museum should be seized upon not only by those with an interest in the revolutionary period but also by students of subjects as diverse as photography and journalism. The Irish revolution was an event that echoed internationally, and documentary photography played no small part in making the case abroad for Ireland’s independence. As this exhibition reminds us, those who opposed that independence also saw opportunity in the medium.

Donal Fallon is a historian and the presenter of the ‘Three Castles Burning’ podcast.