By Cora Crampton

A number of years ago I encountered a difficulty in progressing a promising research topic because of an issue in pinpointing precisely when a particular historical event had occurred. One source indicated that the event, the notorious massacre of the Gaelic ruling classes of Laois at the rath at Mullaghmast in south Kildare, had taken place ‘on the calends of January on Tuesday, 1577’. The ‘calends’ or ‘kalends’ was a Latin term for the first day of every month. Another source, which was the earliest contemporary Irish account of the massacre, was derived from the marginalia of a medical treatise by Laois-based Irish surgeon and scribe Corc Óg Ó Cadhla. The medical scribe wrote in March 1578 of the ‘disgraceful deeds’ which had taken place ‘a short time ago’ at Mullaghmast. It was most unlikely that Ó Cadhla would have described an interval of almost fourteen months in terms of ‘a short time ago’. The dating inconsistency presented a conundrum. It was finally resolved with the realisation that the Julian calendar (and not our Gregorian calendar) had been in use in sixteenth-century Ireland.

THE JULIAN CALENDAR

The Julian calendar, named after Julius Caesar, contained 365 days, commenced each year on 1 January and introduced one leap year every four years. This calendar was inherited from the Roman world by Christendom. Later, the Christian church, in an attempt to dissociate itself from pagan practices, revised the calendar by starting the twelve-month year with a Christian festival. The Feast of the Annunciation on 25 March, marking Christ’s conception, was chosen as the most logical day on which to begin each year. (It is no coincidence that if one counts nine months forward one will arrive at 25 December, the feast of Christ’s birth.)

It was not necessary to delve very deeply to realise that both historical sources had been correct in their reference to the massacre at Mullaghmast. Because 25 March began the new calendar year of 1578, it followed that the preceding months of January and February and up to 24 March belonged to the calendar year 1577. This explains why, at some point in March 1578, Ó Cadhla could refer to an event that happened in January 1577 as occurring ‘a short time ago’, i.e. about twelve weeks earlier according to the Julian calendar. The conundrum had been resolved!

The oddities and difficulties experienced by our ancestors in the western world in the marking of time make for interesting digressions in themselves. For instance, is it not curious that the names for the ninth, tenth, eleventh and twelfth months of our existing calendar are rooted in the Latin for the numbers ‘seven’ (septem), ‘eight’ (octingenti), ‘nine’ (novem) and ‘ten’ (decem)? This made perfect sense when March was the first month of the year.

CALENDAR REFORM

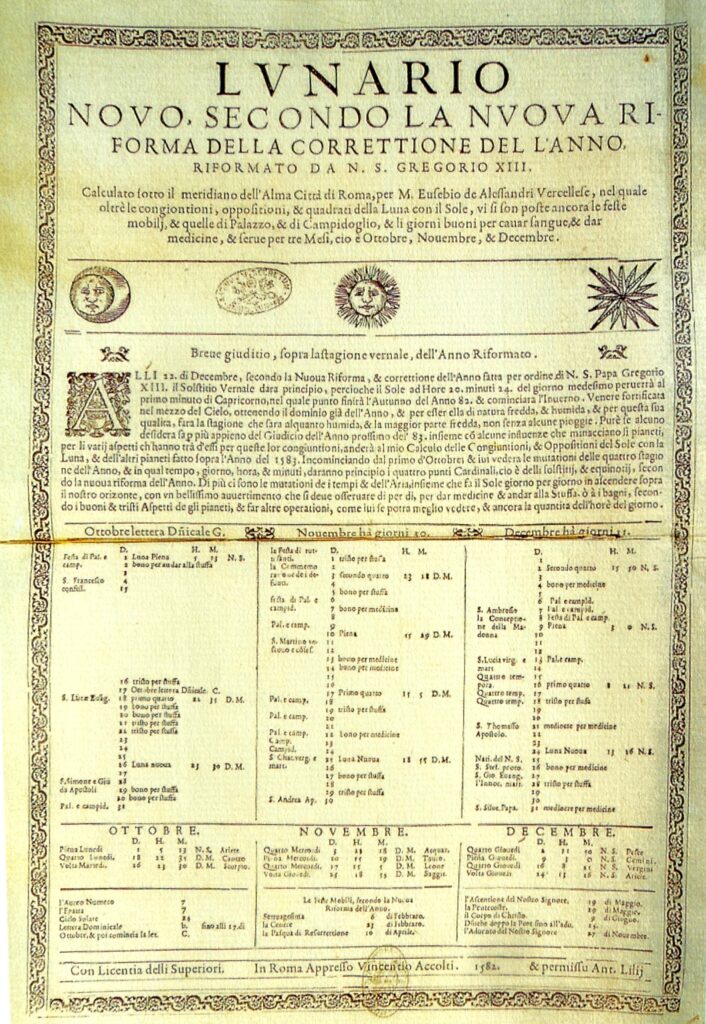

The simplicity of the Julian calendar was one of the reasons why it lasted so long. With the spread of classical astronomy from the Arabic world into Europe, however, it became increasingly evident that the calendar was over-correcting with respect to the seasons; the equinoxes were falling earlier and earlier and the date of Easter was falling later and later. Much scholarly debate ensued as to how to correct the augmenting error. Papal efforts to address this issue proved unsuccessful until 1577, when Pope Gregory XIII disseminated a proposal for reform from an expert commission led by Christopher Clavius (1537–1612) based on the original work of Aloysius Lilius (1510–76) (see above/below). The reforms would realign the calendar with agricultural cycles and the vernal equinox; although these were issues of concern, the Church’s principal motivation was to ensure that Easter and other important feast-days were celebrated at the most accurate times. The misalignment with solar time measured about ten days by 1582, the year in which Gregory XIII finally issued the papal bull that gave Europe the new calendar.

The Gregorian calendar, as it became known, established 1 January as the first day of the new year. In addition, it instituted a once-off elimination of ten days, from 5 to 14 October, to correct the misalignment problem. October was chosen because it was the month with the fewest number of important feast-days. Crucially, this calendar introduced a mechanism which ensured that there would be virtually no more slippage with the seasons in future centuries. The end of centuries (years such as 1600, 1700, 1800, 1900 etc.) would no longer be leap years unless they were divisible by 400. This meant that the year 2000 was a leap year but the year 1900 was not.

ACCEPTANCE AND REJECTION

The majority of Europe’s Catholic states adopted the Gregorian calendar. Its rejection by Protestant states is best understood as a reaction to the reform or counter-reform agenda of the Council of Trent and to the use of a papal bull to pronounce the change, a medium that asserted the authority of the pope. With the exception of Johanne Kepler and Tycho Brahe, many Protestant astronomers and mathematicians expressed opposition to the Gregorian revisions, even though there was widespread acknowledgement in the scientific community of their accuracy and legitimacy. Continued usage of the Julian calendar came to represent a symbol of Protestant confessional identity across Europe. In Bavaria, where the Gregorian calendar was introduced by Maximilian I, Protestant nobles persisted in using the old calendar dates in their correspondence to signify their confessional allegiance.

THE ENGLISH AND IRISH EXPERIENCE

As for the English—and, by extension, the Irish—experience of calendar reform, although Queen Elizabeth I and her secular advisers were in favour of adopting the reformed calendar, the Protestant bishops rejected it in spite of its scientific merits because they were reluctant to take instructions from the pope. The requisite parliamentary bill, which had been drawn up to enact the new calendar, was quietly ignored. Hiram Morgan’s research indicates that before and during the Nine Years War (1594–1603) Hugh O’Neill and his confederates dated their correspondence using ‘the new computation’. This gesture, intended to align their cause with Catholicism, may also have been a provocative exercise in political grandstanding.

In the years that followed, two different starts to the year were recognised in Ireland. Almanacs began to include two calendars, and the double-calendar quickly came into widespread circulation. Almanac headings juxtaposed the two calendars as follows: ‘The English account’ with ‘The Romish account’; the ‘Old’ with the ‘Forrain’; the ‘Usuall’ with the ‘Reformed’; and the ‘Julian or English, used in great Brittain’, with the ‘Gregorian or Roman used beyond the Sea’. The Gregorian days and numbers were often printed in Latin and in roman font to give them a learned but also a Catholic and alien look, whereas the ‘English’ dates were often printed in familiar blackletter font. One of the earliest almanacs to refer to the new calendar was produced by William Farmer, a surgeon, who calculated it for Dublin in 1587 and prudently advised that travellers and those merchants who traded abroad should familiarise themselves with the new method of keeping of time in other countries:

‘The common almanacke … Whereunto is annexed, and diarily compared the new Kalendar of the romans, which is very pleasaunt, and also necessarie for all estates, whosoever that hath cause to travel, trade, or traffique into any Nation which hath already received this new Kalendar; as wyll more playne appear by the daily use thereof.’

Although the official year continued to start on 25 March or Lady Day, an awareness of the Gregorian calendar meant that New Year’s Day came to be increasingly celebrated on 1 January. Indeed, the English diarist Samuel Pepys, when writing in his journals from 1660 to 1669, marked the start of each new year on 1 January.

THE CALENDAR (NEW STYLE) ACT

Protestant states across western Europe gradually set aside their objections to calendar change in the eighteenth century, the age of Enlightenment, not least for the benefit of trade, commerce and scientific precision. The Julian calendar continued to function as the official calendar in Great Britain, Ireland and the British colonies (including America) until 1752, when the government finally embarked on calendar reform. The change-over required an act of parliament, the Calendar (New Style) Act, which was introduced by Philip Stanhope, the 4th Earl of Chesterfield.

The necessary adjustments were made in two stages. It was decreed that the official year 1751 would no longer end on 24 March (Old Style) but would instead end on 31 December 1751 (New Style). The next day, 1 January, would be the first day of 1752. Another important change introduced the necessary refinement for the reckoning of end-of-century leap years ‘in all times coming’. Finally, in order to correct the misalignment with solar time, which had by then grown to eleven days, the Act stipulated that eleven days would be removed from the month of September 1752, so that Wednesday 2 September would be followed by Thursday 14 September. During and after the transition period the terms ‘Old Style’ and ‘New Style’ were used to distinguish between the two calendars.

In his regional study of the reception of the Gregorian calendar across Britain in 1752, Professor Robert Poole cleared up a long-standing urban myth concerning the supposed ‘calendar riots’. There is no evidence to substantiate the claim that English rioters demanded that the government should give them back their eleven days in protest against the introduction of the calendar. The myth originated with William Hogarth’s boisterous painting The Humours of an Election 1: An Election Entertainment (1755). Hogarth depicts a black banner on the floor which carries the inscription ‘Give us our Eleven days’, suggesting an unease amongst the poorly educated that the government was stealing eleven days of their lives.

TAXATION AND THE CALENDAR

In order to alleviate the potential for financial hardship, the 1750 Act provided that, where necessary, rents and other dues would be deferred by eleven days. Because taxes were payable on the first day of the ‘Old Style’ calendar, i.e. on 25 March, eleven days were added on, so that taxes became due instead on 6 April each year. Our neighbours in the United Kingdom continue to this day to operate a tax year beginning on 6 April. The Republic of Ireland, on the other hand, moved to align the Irish tax year with the calendar year, effective from 2001. The Finance Act (2001) also catered for changes necessary for the transition from the Irish pound to the Euro, thereby facilitating two sets of income tax changes. A shorter 39-week tax year applied from 6 April to 31 December 2001, after which the first new full financial year commenced on 1 January 2002. Many annual reliefs and allowances were apportioned for 2001 and new tax filing and compliance dates introduced. All told, it was a successful change-over and ensured that Ireland was in step with the fiscal cycles of other major economies.

CONCLUSION

It is clear that calendars are much more than mere exercises in calculations and reckonings. For 170 years the calendar represented a symbol of confessional identity in western Europe. Two different methods of marking time gave rise to concomitant fiscal and administrative difficulties for trade, commerce and daily life. (Parallels with Brexit come readily to mind!) Yet the Gregorian calendar is in widespread use across the globe today principally because of the reach of the British Empire. Its accuracy is such that only when our descendants arrive at the year 3719 will this calendar be one full day out of kilter with solar time. But let us spin on. Our world presents us with many more pressing problems.

Cora Crampton is secretary of the West Wicklow Historical Society and a prize-winning historical author.

Further reading

J. Power McNutt, ‘Hesitant steps: acceptance of the Gregorian calendar in eighteenth-century Geneva’, American Society of Church History 75 (3) (2006), 544–62.

A. Lake Prescott, ‘Refusing translation: the Gregorian calendar and early modern English writers’, Yearbook of English Studies 36 (1) (2006), 1–11.

E.G. Richards, Mapping the calendar and its history (Oxford, 1998).