By Stephen Griffin

Irish émigrés are recorded in the Iberian peninsula from the sixteenth century onward, as noblemen and clergymen sought support from Habsburg Spain against the Tudor monarchy. Irishmen also served in the Spanish Low Countries during this time. Increased numbers of military exiles arrived in Spanish dominions following the Irish defeat in the Nine Years War. This amplified level of service continued throughout the seventeenth century, as Irish regiments fought for Spain against England, France and the Dutch Republic. During the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14) Irish soldiers in the service of Louis XIV of France were dispatched to Spain to support his grandson, Philip, Duke of Anjou, as a claimant to the Spanish throne. Here they served in five regiments of infantry and two of dragoons during the war that would see Anjou crowned Philip V of Spain. By the 1740s, three Irish regiments of infantry remained in Spain, Irlanda, Hibernia and Ultonia, in addition to one of dragoons, Edimburgo.

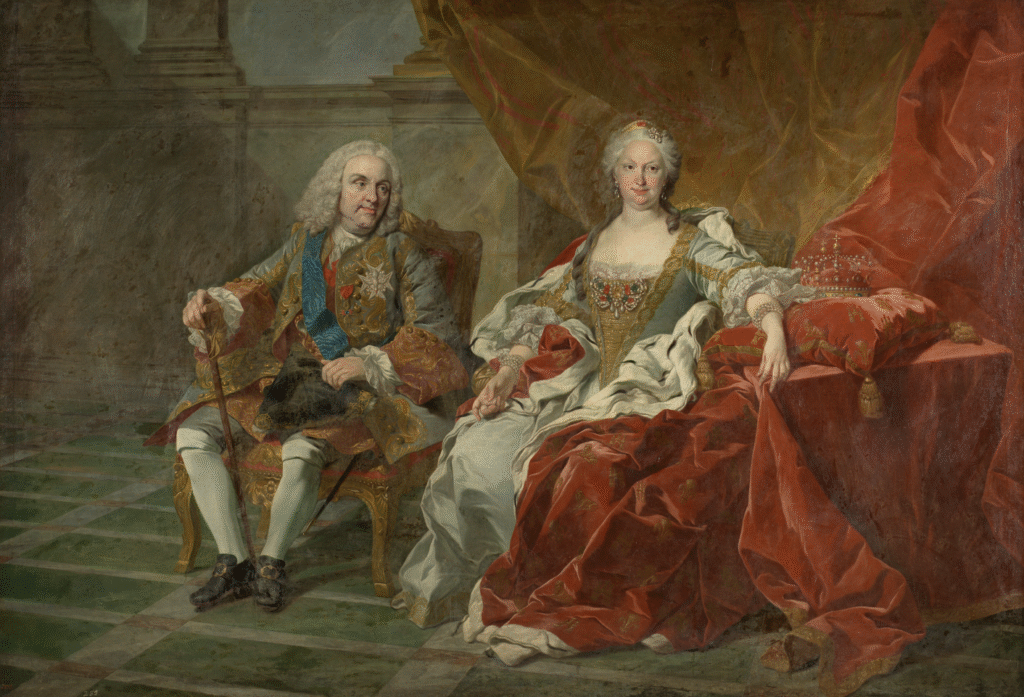

Philip V was a childhood friend of the Stuart court-in-exile’s figurehead, James Francis Edward, and had fostered the settlement of Jacobites in Spain. The formation of an Irish interest group at Philip’s court saw the creation of strong connections to the new Bourbon monarchy and provided Irish émigrés with opportunities for social advancement. Philip’s second wife, Elisabeth Farnese, was determined to secure an inheritance for her children in Italy. As a result, Spain sought to reconquer Italian dominions that it had lost during the War of the Spanish Succession. The Jacobites provided a diversionary tool which enemies of Britain could make use of in times of conflict. War with Britain and her allies (1718–20) ensured that the Spanish would back the short-lived 1719 Jacobite rising, which culminated in the Battle of Glenshiel. Philip and Elisabeth then provided erratic support to the Stuarts throughout the 1720s and 1730s (often for their own gain).

Disputes between Spain and Britain over trade and territory in Latin America culminated in the War of Jenkin’s Ear in 1739. This conflict was eventually subsumed by the larger War of the Austrian Succession (1740–8), which pitted Britain, the Habsburg monarchy, Russia and the Dutch Republic against France, Spain and Prussia, amongst others. Against this backdrop, James’s son, Charles Edward Stuart (‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’), arrived in Scotland to launch a new Jacobite rising in August 1745. Having been in France since January 1744, Charles set sail for Scotland aboard the Du Teillay on 3 July 1745. On 3 August he reached Loch Eriskay in Scotland and disembarked. Antoine Walsh, the captain of the Du Teillay, returned to France in September 1745 with this news. The stories of the ’45, of Charles’s arrival in the Highlands, his march to Derby, the Jacobite defeat at Culloden, the subsequent flight of the prince through the heather and the suppression of the Jacobites by the Duke of Cumberland have been recounted numerous times. That the rising received support from France is also well documented. Efforts by Irish soldiers in Spanish service to aid Charles, while occasionally mentioned briefly in passing, are worthy of additional attention.

SOLICITATIONS

Prior to his departure, Charles requested support from Spain via his aide, Francis Stafford, but the task of soliciting aid fell chiefly to Sir Charles Wogan. Born in Rathcoffey, Co. Kildare, Wogan had fought in the Jacobite rising of 1715. Imprisoned after its defeat, he subsequently escaped to France. In 1718 he then carried out the mission with which he will always be associated when he rescued Princess Clementina Sobieska (Charles’s mother) from her imprisonment in Innsbruck and whisked her across the Alps to the Stuart court in Italy. The rescue made Wogan an instant celebrity and he was made a senator of Rome by the pope and a knight-baronet by the Stuart court. Settling in Spain, Wogan ultimately served in the Regimiento de Irlanda and was appointed governor of the province of La Mancha. He received instructions from Charles on 26 July 1745 and travelled immediately to the royal palace of La Granja de San Ildefonso. There he learned that the Spanish court judged Charles’s actions to be heroic but rash and dangerous. As Philip V would only act in conjunction with Louis XV, Wogan did not receive any immediate answer to his requests for help.

In an audience with Louis XV, the Spanish ambassador to France, Luis Reggio Branciforte y Colonna, Prince de Campoflorido, highlighted that the rising would cause an immense distraction in Britain regardless of its success. Campoflorido told the French that if they supported the Jacobites then Spain would follow suit. It was decided that France would match the quantity and supply of all weapons, money and materials sent by Spain. Once word of this reached the Spanish court, Wogan received promises for 100,000 crowns, 10,000 muskets, 500 quintals of powder and 600 quintals of musket-balls, as well as ‘some Irish officers’ whom he would hand-pick. Transport to Scotland would be provided via four frigates to be armed in La Coruña and San Sebastián. They would sail under cover of being destined for the Canary Islands. Much to Wogan’s frustration, and despite reports from the news gazettes reporting Charles’s arrival in Scotland, the frigates could not depart until Charles’s landing had been confirmed by Spanish diplomats in Paris and the Hague. This confirmation was not received until the first week of September.

A letter between Spanish ministers noted that Wogan had picked officers for the mission in September 1745. These were officers from the regiments of Edimburgo, Irlanda, Hibernia and Ultonia, along with engineers and civilian volunteers. Roughly 50 men, with surnames such as Bourke, Carroll, Creagh, Cummins, Fitzgerald, Galwey, Kindelan, Lacy, MacMahon, MacSwiney, O’Brien, O’Conor, O’Gara and Purcell, were recommended and pardoned by the Spanish court to join Charles’s army. The officers were stationed in cities such as Madrid and Barcelona in addition to Spanish overseas possessions in Italy and in North Africa in Ceuta and Oran. There were problems with some of the men Wogan had chosen. Captain Daniel Hickey in the Regimiento de Ultonia had killed a fellow officer, presumably in a duel, while on garrison duty. He was awaiting court martial for the offence and in his stead Wogan suggested a lieutenant named Hugo de Lacy from the same regiment.

‘A PEAR TO QUENCH THEIR THIRST’

Francis Stafford, who had been sent to Spain by Charles, was to sail with the first ship. As Stafford was not a soldier, he received a captaincy of horse. A Captain French from the Regimiento de Edimburgo would take the second, and the third would sail under Don Juan Lophtus. Like Stafford, Lophtus was not a soldier and received a captaincy. French was provided a lieutenant colonelcy for the expedition. As Wogan was ill from fever and jaundice, he would lead the fourth frigate from La Coruña once he had recovered. This eventually departed without Wogan and under the command of Ultano Kindelan, who was promoted to lieutenant colonel. In late October Kindelan’s ship reached western Scotland, and he left his cargo on the Isle of Barra. Of the other frigates, Stafford’s ship was captured by privateers near Bristol in October 1745, while another was captured and brought into Cork harbour. Another ship was lost to bad weather.

The initial plan between Wogan and the Spanish court was that a second convoy would sail with more materials and would carry the officers chosen from the garrisons in Italy and North Africa. This did not materialise. Towards the end of 1745 Wogan proposed that the Spanish transport men from the Irish regiments to Wales. As the regiments were understrength, they would raise levies in Wales and England in support of Charles. Wogan requested 60 officers, 30–40 sergeants and ten to twelve drummers to aid in filling levies for this Jacobite army. Because Irish officers were (in Wogan’s words) unable ‘to keep a pear to quench their thirst’, he also requested that they be provided with 40–50 Spanish pistoles per head or a gross sum of 2,000–3,000 pistoles. This would pay their travel expenses. Wogan hoped that the expedition would be ready to depart early in 1746, but nothing came of this proposal.

It was increasingly clear that aid from the Spanish court would not be of great assistance. The French minister for foreign affairs, René Louis de Voyer de Palmy, Comte d’Argenson, complained that Spain was not pulling her weight in aiding Charles. France had meanwhile sent the same amounts of ammunition and funding as the Spanish, in addition to two battalions and two squadrons of soldiers. Overall, they dispatched a total of 34 ships carrying men, arms and supplies to the Jacobites over the course of the rising. As the French now began preparing an invasion force to land in England, they advised the Spanish to do the same. When it was made clear that Spain could not send such a force, it was agreed that France would supply 2,000 men, which the Spanish Crown would pay for. These would be commanded by the Irish officers chosen by Wogan.

ENDGAME

French ships continued to carry materials and supplies, and Irish officers from Spain were transported by these to Scotland. Officers also made their way to Boulogne and Calais, where French troops gathered for a planned expedition to England. One of these, Felix O’Neill, an officer from the Regimiento de Hibernia, sailed in February or March 1746. Appointed to Charles’s staff, O’Neill became a close companion of the prince in the aftermath of Culloden.

Word reached France of the Jacobite retreat from Derby in the middle of December 1745. This made the French rethink their plans, as all certainty of an invasion force being able to link up with Charles’s army now vanished. Despite orders to embark in January 1746, the invasion did not go ahead. Waning French commitment and indecision, combined with the activities of the Royal Navy, ensured that there would be no expedition to support Charles. By February 1746 invasion plans had been abandoned.

Officers from Spain had continued to file into France. In February, Juan MacDonnell, Francisco Luttrell and Thadeo O’Beirne from the Regimiento de Irlanda and Dominic Reilly, James Butler and Patricio Savage from the Regimiento de Hibernia arrived in Lyons en route to Paris. MacDonnell wrote that he did not have sufficient funds for his journey and planned to seek aid from the Irish College in Paris. Elsewhere, Wogan sought funding from Madrid to pay for the travel expenses of cadets journeying to Dunkirk. As news arrived of Charles’s declining fortunes and the Jacobite army’s failure to capture Stirling Castle in March 1746, there were reports that officers now had second thoughts about joining the prince. Nevertheless, as late as 18 April (two days after the Jacobite defeat at Culloden) Wogan left Paris with twenty officers, planning to embark for Scotland. They never departed.

News of the disaster at Culloden reached the French in May. Having abandoned the remnants of his army, Charles returned to safety via a French ship in September 1746. Blamed for the loss of the Spanish frigates, Wogan had been recalled to Spain that July and returned to his governorship in La Mancha. The Spanish embassy in France received appeals to secure the release of men who had been imprisoned in Scotland. Ultano Kindelan, who had captained one of the Spanish ships, was captured at Culloden. Felix O’Neill, having escaped with Charles to the Outer Hebrides, was taken prisoner in July 1746 and imprisoned in Edinburgh. Both Kindelan and O’Neill and many others were released in prisoner exchanges in 1747. After their brief period of involvement in the events of 1745–6, Spanish support for the Jacobites fizzled out thereafter. Philip V died in July 1746 and Charles, increasingly unwelcome in France, visited Madrid in 1747. Serving only to embarrass the Spanish, he was unable to secure any meaningful aid.

Stephen Griffin formerly lectured in History at the University of Limerick and is currently employed by Limerick Civic Trust.

Further reading

S. McGarry, ‘The battle of Culloden: the Irish connection’, History Ireland 29 (2) (2021), 22–5.

F. McLynn, France and the Jacobite Rising of 1745 (Edinburgh, 1981).

É. Ó Ciardha, ‘Wogan, Sir Charles’, in the Dictionary of Irish Biography.

Ó. Recio Morales, Ireland and the Spanish empire (Dublin, 2010).