By Anthony Barrett

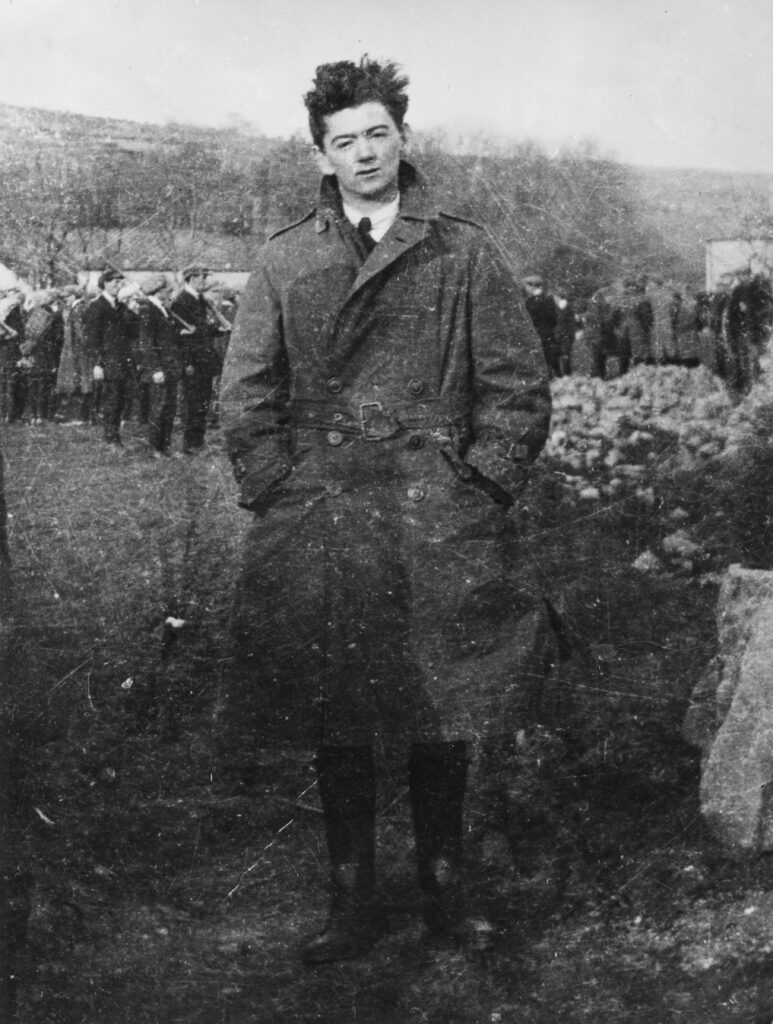

Over the winter months of 1922/3, by which time the Irish Civil War had devolved into a gruelling stalemate, the legendary and controversial IRA commander Tom Barry led a guerrilla campaign in Tipperary. His most prominent action was the capture and destruction of the National Army barracks at Carrick-on-Suir. In Green against green, perhaps the definitive book on the Irish Civil War, Michael Hopkinson wrote of Barry’s activities in the Premier County: ‘There is no evidence that Barry had taken over as Director of Operations in the 2nd Southern Division, or that he was acting under instructions in taking Carrick; he remained a law unto himself’.

Though many would agree that this is an apt description of Tom Barry, Hopkinson had not consulted a collection of documents now known as the Moss Twomey Papers. These are the archives of the IRA’s general headquarters from 1922 to 1932, once held by IRA Chief of Staff Maurice ‘Moss’ Twomey and donated by his nephew to UCD in 1984. Contemporary communications in this collection reveal the true role of Tom Barry in Tipperary during the closing months of the Civil War.

CIVIL WAR

Tom Barry was in Cork when the National Army surrounded the Four Courts early on the morning of 28 June 1922 and began shelling it with artillery. On learning of this, he immediately got an IRA transport officer to drive him to the capital. After a misguided attempt to get through the National Army cordon surrounding the Four Courts disguised as a Red Cross nurse, Barry was detained and imprisoned. He escaped custody in late September and made his way back to West Cork, by which time the National Army had garrisons in all major towns in the country and the IRA had reverted to guerrilla warfare to make the new Free State ungovernable.

Tom Barry presented himself at First Southern Division headquarters in Coppeen, Enniskeane, on the day the National Army in West Cork carried out a great sweep through Ballingeary and Ballyvourney, the heartland of IRA-controlled territory in this region. He was immediately given command of a column and ordered to lie in ambush at Kilmichael for the expected return from Ballyvourney of a National Army column led by his former comrade General Seán Hales (ultimately no fighting occurred). After this Barry began to reorganise the West Cork guerrilla columns into a single large formation to carry out town attacks.

SOUTHERN COMMAND

About two weeks after his return to active service, Barry was called, along with First Southern Division commander Liam Deasy, to a meeting of the IRA’s governing Executive at a farmhouse near Newcastle, Co. Tipperary, where IRA Chief of Staff Liam Lynch announced the formation of Southern Command, incorporating all of Munster, Offaly, Laois, Kilkenny and Wexford, under the direct command of Liam Deasy, who was promoted to IRA Deputy Chief of Staff. Tipperary IRA officer Con Moloney was appointed as his adjutant and Tom Barry was appointed as Southern Command’s Director of Operations. His role would be to organise large columns in each of its divisions, primarily to attack National Army town garrisons. Barry proposed that he would go to each division to develop its divisional column and then take temporary command of it for at least one spectacular operation.

After the Executive meeting, Liam Deasy moved with Moloney to a new headquarters at Tincurry near Cahir, while Barry commenced operations in the First Southern Division with the column he had already developed there. His first target was intended to be the Bandon garrison in the Cork Third Brigade area, but at the last minute he switched the attack to the nearby twin villages of Ballineen and Enniskeane. After this the divisional column moved west to the Ballingeary–Ballyvourney district. He planned to attack Inchigeelagh barracks in mid-November but faced reluctance from Cork First Brigade officers to participate. Barry proceeded regardless and recommissioned the brigade’s only armoured vehicle, a coal lorry plated with ship-iron named the River Lee, to smash through the barracks’ defences. The garrison in Macroom learned of his plans and sent out reinforcements, forcing Barry to call off the operation.

CARRICK-ON-SUIR

At the end of November Barry assembled a staff of loyal West Cork officers and departed for Deasy’s headquarters in Tincurry. Deasy and Barry held a council meeting of the Second Southern Division (South Tipperary and Kilkenny) in Rosegreen on 2 December, at which Barry was placed temporarily in charge of operations in the division, working with divisional O/C Operations Bill Quirke. Cognisant of the difficulties he experienced with the Cork First Brigade, Barry got assurances from Third Brigade commander Dinny Lacey that his volunteers would co-operate fully with the Corkmen.

Over the following week Quirke arranged for the active IRA columns in the Tipperary Third Brigade area to mobilise with Barry’s men at Grangemockler, near Slievenamon. Their target would be the National Army garrison occupying the workhouse at Carrick-on-Suir and the date fixed for the attack was the evening of Saturday 9 December, when many of its soldiers would be on leave in the town. Carrick-on-Suir had been captured by General John Prout in August but had experienced little republican activity since, and its garrison was considered complacent and ill-disciplined.

Barry planned the operation with characteristic attention to detail. The column was divided into four sections: one to surround the town and block every road, one to storm the gatehouse, one to take the main barracks buildings and one to round up soldiers in the town. While preparations were under way on Friday they received shocking news—General Seán Hales had been assassinated in Dublin the previous day, and early that morning four senior republican officers in prison had been executed in retaliation. Barry was especially stunned, as he had known all the deceased personally. The republicans resolved to continue with their attack.

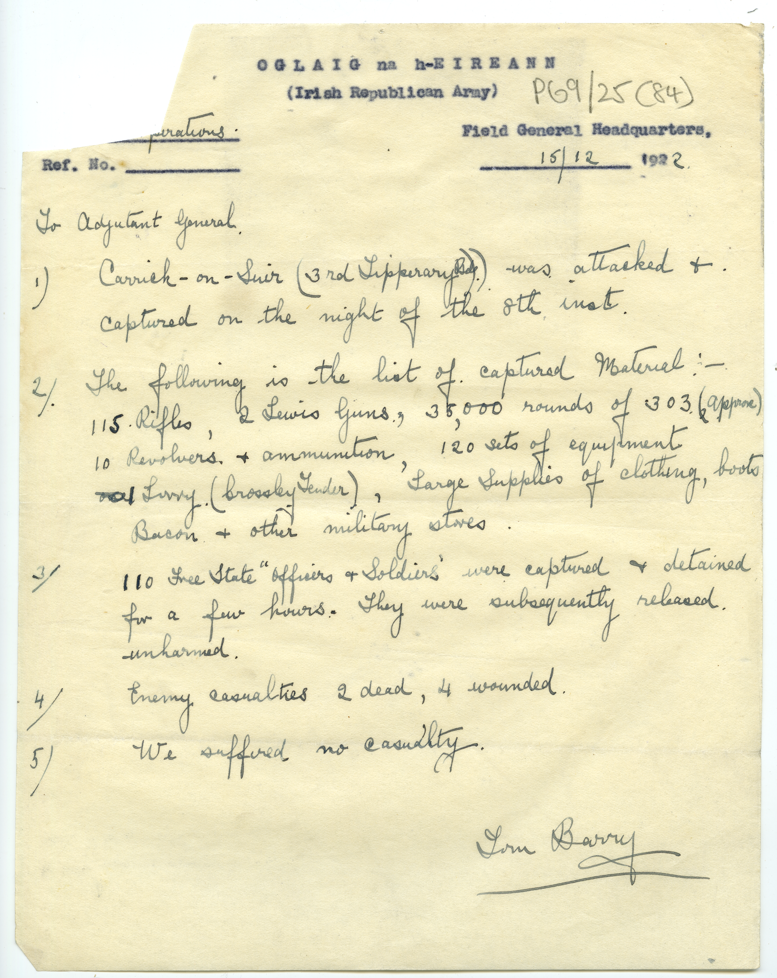

As darkness fell on Saturday the column left Grangemockler, marching south past Kilcash Wood and on towards Carrick-on-Suir, with Barry in overall command and leading a section. Around 9pm Barry ordered his section to remove their boots, and they advanced silently along the Clonmel Road towards the workhouse gatehouse. Wearing a National Army uniform, Barry walked up to the sentry, whom he assaulted and silenced. Dinny Lacey led the section into the gatehouse, which was swiftly taken without an alarm being raised. Bill Quirke’s section then stormed into the main buildings. With his troops taken completely by surprise, Commandant Francis Barrett surrendered without a shot being fired. The remaining National Army troops in the town, most of whom were at the cinema, were rounded up and brought back to the workhouse. National Army officer Lieutenant James Gardiner was shot and killed in the town when he challenged approaching republicans. The contents of the workhouse, including 115 rifles and 35,000 rounds of ammunition, were loaded onto commandeered lorries and whisked off to hideouts up in the mountains; the workhouse was then set on fire and partially destroyed. The humiliated National Army prisoners were released, and the triumphant republicans fled.

The spectacular attack on Carrick-on-Suir appeared to be a vindication of Barry’s tactic of the large divisional column. He moved his own men west to Cloghera in the Glen of Aherlow and then returned to the Tincurry HQ, from where he issued detailed instructions to all divisions on forming their own divisional columns and assessing target strengths. Meanwhile, Lacey and Quirke moved on to Kilkenny, where their column raided the barracks in Callan on 14 December and Thomastown and Mullinavat on the 15th, using a combination of subterfuge and defecting National Army officers, and all without a shot being fired.

These raids were a major humiliation for the National Army, which took immediate and aggressive steps to ensure the curtailment of further republican operations. An effective intelligence-gathering system was put in place to seek out republican hideouts, and large formations of National Army troops began carrying out extensive sweeps of the countryside.

KEEPER HILL

Tom Barry returned to West Cork for Christmas and developed an ambitious strategy for the new year. He set his sights on the barracks in Nenagh and Roscrea in the Third Southern Division (North Tipperary, Laois and Offaly), planning to capture artillery and armoured vehicles to be used in ever-larger spectacular raids, which would ultimately force the government to negotiate ceasefire terms amenable to republicans. To bolster the weak IRA organisation in this division, he recruited experienced Cork officers to be deployed within it, including Beál na Bláth ambush veteran Denis ‘Sonny’ O’Neill and Ballyvourney officer Patrick J. Lynch.

In early January they arrived at the Glen of Aherlow, where Barry informed Liam Deasy of his plans. A week later they moved north to the headquarters of Third Southern Division commander Matt Ryan at Farrell’s of Curreeny, high up in the Silvermines Mountains, where they were joined by a Limerick column led by Seán O’Carroll.

Subsequent events at Curreeny, recounted by Pat Lynch to Ernie O’Malley years later, show why Tom Barry was Napoleon’s favourite type of general—a very lucky one. At dawn on the morning of 23 January a National Army column led by Col. Commandant Michael J. Costello swept into the district and attempted to surround the republican hideout. Barry ordered a ferocious defence. His column managed to fight off the encirclement and escape west towards Keeper Hill. As they were crossing open ground, Lynch was hit by a bullet in the heel, though he was able to keep running, but Kilmichael ambush veteran Jack Hennessy was struck in the hip and incapacitated. Barry and the others hastily fashioned a stretcher from two rifles and a trench coat and carried him onwards up the mountain. Another National Army column closing in from the Limerick direction inadvertently stayed too far south, allowing Barry and his men to conceal themselves in the fog enveloping Keeper Hill. They remained in the open on the mountainside all night, reaching a safe house and medical help the following morning. Leaving behind their injured and ‘Sonny’ O’Neill to direct division operations, Barry and his remaining men kept on the move, evaded National Army patrols and returned to the Glen of Aherlow at the end of January.

ENDGAME

By now, relentless National Army sweeps, captures and killings had effectively destroyed the IRA’s organisation in Tipperary. Liam Lynch ordered Barry to move south to the First Southern Division and direct operations from there, but he was still in the Glen when he received the letter that changed everything.

Liam Deasy had been captured in the Galtee Mountains above Tincurry in late January, tried and sentenced to death. The sentence was suspended after he agreed to issue a letter to each member of the IRA Executive calling for an unconditional surrender. After receiving this, Barry ceased his offensive operations and ordered First Southern Division commander Tom Crofts to come to the Glen to discuss the way forward. Both agreed that the Executive should immediately debate Deasy’s letter, and they went to Liam Lynch in Dublin to request a meeting of the Executive. Lynch obstinately refused.

Barry and Crofts returned to Gougane Barra in West Cork. Offensive operations in Southern Command remained suspended while they persisted with calls for an Executive meeting. Barry had already been in direct contact with officers of the National Army’s Cork command since his return in September; now he engaged in ceasefire negotiations in earnest, though he would vociferously argue that he was the conduit between the Irish clergy, National Army officers and the IRA’s Executive rather than an instigator of peace moves himself. Regardless, the ending of his aggressive campaigning in Southern Command hastened the end of the tragically futile Civil War.

Anthony Barrett is the author of West Cork at war—the forgotten guerrilla campaign 1922 (Eastwood Books, 2025).

Further reading

L. Deasy, Brother against brother (Cork, 1998).

M. Hopkinson, Green against green: the Irish Civil War (Dublin, 2004).

F. O’Donoghue, No other law (Dublin, 1986).

Ernie O’Malley interviews, Moss Twomey Papers, UCD Archives.