By Pádraig Óg Ó Ruairc

One spring morning in 1923 Rotha Lintorn-Orman, former head of the British Red Cross Motor School during the First World War, was weeding her kitchen garden in Somerset, England, when she was struck by an idea. She was an admirer of Mussolini and delighted in reading about his exploits in her morning newspaper but was infuriated after turning the page and reading that Britain’s Labour Party was attending a European socialist conference. She vented her anger by working in the garden and concluded that Irish Republicans, Bolsheviks and other radicals needed to be rooted out of the British Empire in the same way that she tore the weeds from her vegetable patch. Lintorn-Orman founded the British Fascisti in May 1923 after publishing adverts seeking recruits willing to fight against ‘Red Revolution’ throughout the British Empire. The principles of her movement were ‘The King, class friendship, preferential treatment of ex-servicemen, the purification of the British race’ and the protection of Britain from Irish Republicanism, Anarchism, Communism, Socialism, Trade Unionism, Atheism and ‘free love’. Furthermore, Lintorn-Orman declared, ‘the moral, spiritual and fundamental objects of British Fascism and Mussolini’s Italian Fascists are identical’.

‘FREE STATE COMMAND’ AND ‘ULSTER COMMAND’

One of the earliest units of the British Fascisti was established in Dublin within weeks of the ending of the Civil War. ‘The British Fascisti—Free State Command’ opened a headquarters in the capital and Gardaí estimated that they had 30 active members in Dublin, with several hundred supporters and subscribers. The British Fascisti soon established an ‘Ulster Command’ with active units in Belfast, Newry, Newcastle and Kilkeel. At the height of their activity there were several thousand members of the British Fascisti throughout Britain and Ireland. Given the organisation’s jingoistic promotion of the British Empire as a bulwark against an imagined Irish Republican, Bolshevik and Jewish-led global conspiracy, it is unsurprising that all of their members in Ireland were either Southern loyalists or Ulster unionists. Many of the British Fascisti’s Dublin members were former RIC constables or retired British Army officers.

The organisation north of the border was little different and was led by two controversial loyalists. The first was Captain E.G. Morgan, a former Ulster Special Constabulary officer who was forced to resign from the force in 1924 after his fellow officers complained that he ‘was a source of trouble to Roman Catholics … He was actually seen writing filthy inscriptions on the walls of their houses.’ An internal inquiry found him guilty of ‘an act judged prejudicial to the good order and discipline of the Force’. The fact that Morgan was kicked out of a paramilitary police force which had a well-deserved reputation for religious bigotry, indiscipline, violence and sectarian murder for being too extreme says a lot about his character. Morgan’s female counterpart as deputy leader of the British Fascisti in Belfast was Dorothy Hartnett, an Englishwoman whose father, Colonel Henry Waring, had moved his family to County Down to take up a commission in the Ulster Special Constabulary. During the War of Independence Hartnett volunteered as a ‘lady police searcher’ with the RIC. After she transferred to the RUC in 1922, numerous women lodged complaints of harassment and sexual assault against her for being overzealous when carrying out strip searches of suspected republicans. These complaints led to her dismissal from the RUC in March 1923.

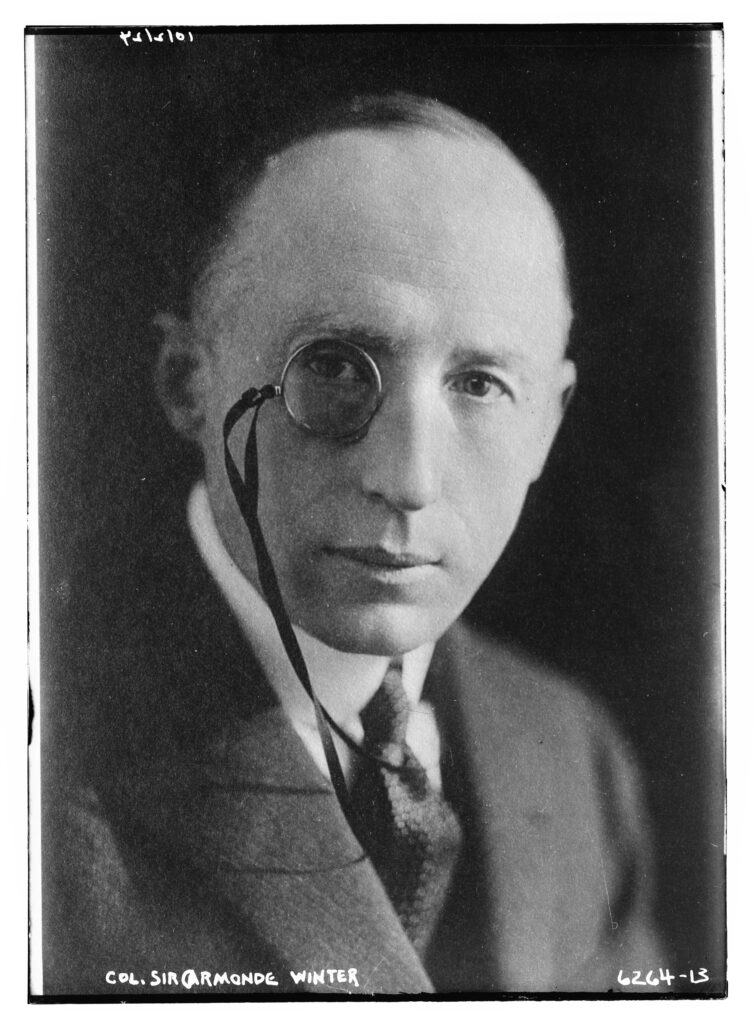

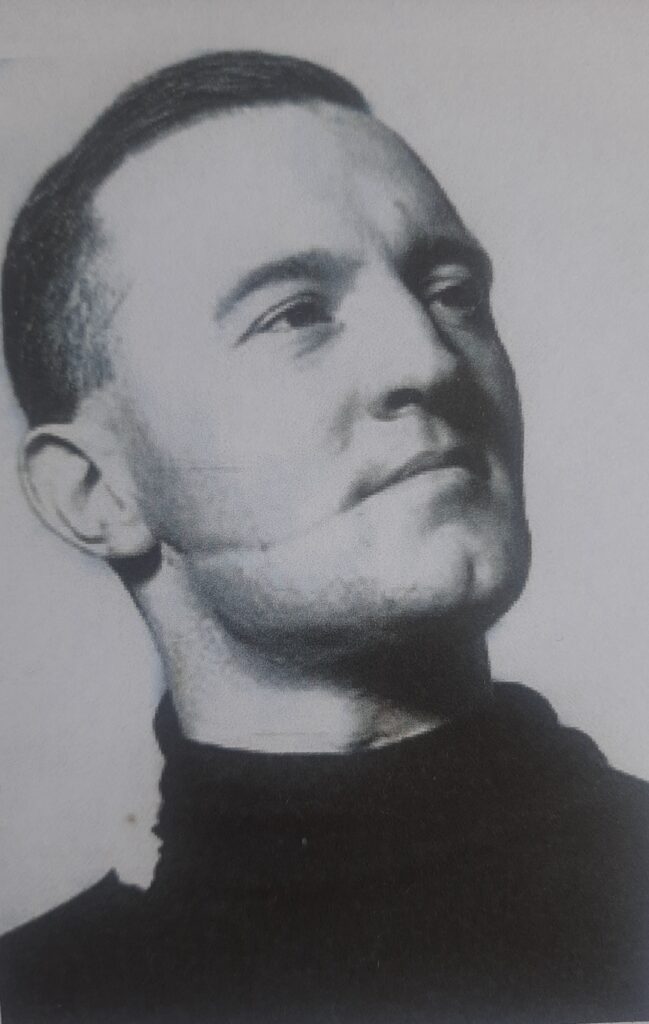

Several leading figures in the group’s ‘England Command’ were also veterans of Britain’s fight against the IRA. These included Sir Ormonde Winter, who had been chief of intelligence at Dublin Castle. Winter was appointed officer commanding of the British Fascisti’s London unit in 1923 and immediately began stockpiling machine-guns and other illegal arms for the movement in the hope of leading a fascist coup. Another was William Joyce, better known later as ‘Lord Haw Haw’, the Galway man who was an informer for the Black and Tans during the War of Independence. Joyce managed to evade his would-be IRA assassins, escaping to England to become a fascist agitator. Two decades later he was hanged by the British for broadcasting Nazi propaganda during the Second World War.

OFFICIAL UNIFORM

Initially the British Fascisti did not have an official uniform, though many of its members opted to wear black shirts in imitation of Mussolini’s followers. However, all members were required to sport a black handkerchief and wear the organisation’s badge on their left breast. The badge was of a circular design in black enamel with silver detail and featured a capital letter F (representing Fascism). This was encircled by a scroll reading ‘FOR KING AND COUNTRY’, surmounted by a crown. Although the Italian Fascist ‘Roman salute’ was popular with some members, Lintorn-Orman modified it in an effort to create a distinctly British form. This involved members of the British Fascisti standing to attention and ‘bringing the right hand across the chest and touching their membership badge’. In a further attempt to distinguish themselves from their Italian counterparts, the British Fascisti later adopted an official uniform consisting of a blue shirt, black beret and black trousers for men, with women wearing a black skirt. This was almost a decade before Eoin O’Duffy’s fascist followers adopted an almost identical ‘Blueshirt’ uniform.

Aside from harassing members of Dublin and Belfast’s tiny Jewish communities, or publishing and distributing anti-Semitic conspiracy theories, the British Fascisti’s main activity in Ireland throughout the 1920s centred around Armistice Day each November. In the early 1920s uniformed members of the British Fascisti patrolled Dublin’s First World War commemorations brandishing revolvers to enforce at gunpoint the two minutes’ silence to honour ‘the Glorious Dead’. (The same method of enforcing ‘respect’ had been employed by their Black and Tan predecessors in Dublin a few years earlier.) The British Fascisti worked in close co-operation with the Dublin branch of the Royal British Legion throughout the 1920s to promote the sale of poppies, and to protect poppy-sellers from attacks and harassment by Irish Republicans. In later years the British Fascisti campaigned for ‘Armistice Day’—or, as it became, ‘Remembrance Sunday’—to be renamed ‘Fascist Sunday’.

The British Fascisti met frequent violent opposition from the IRA throughout the decade when they had a presence in Dublin. Rioting, attacks and street battles between the two groups were common, resulting in a failed attempt to have the Protestant IRA leader George Gilmore prosecuted after he stabbed two members of the British Fascisti during a fight on Grafton Street in November 1926. On another occasion the IRA attacked and burned down the British Fascisti’s Dublin headquarters.

The British Fascisti’s fortunes fell in tandem with the demise of ‘the Founder’, Rotha Lintorn-Orman. By the 1930s the movement was struggling financially after her mother stopped the generous financial allowance that had funded her daughter’s political ambitions when she learned of Rotha’s drug habit and began hearing lurid tales of alcohol-fuelled orgies at her home. Despite receiving some financial assistance from Nazi Germany, the movement folded in 1934 when Lintorn-Orman’s hedonism and substance abuse led to her death at just 40 years of age. The leadership of the British Fascisti passed briefly to Dorothy Hartnett but, despite her best efforts, the movement soon collapsed. Undeterred, Hartnett continued her political activism with the Ulster Protestant League, and throughout the Second World War she continually campaigned on behalf of Nazi Germany. Hartnett died alone, forgotten and in complete political obscurity in a nursing home in 1977.

Pádraig Óg Ó Ruairc is the author of Burn them out!—A history of Fascism and the Far-Right in Ireland (Bloomsbury/Head of Zeus, 2025).