By Christopher S. Connelly

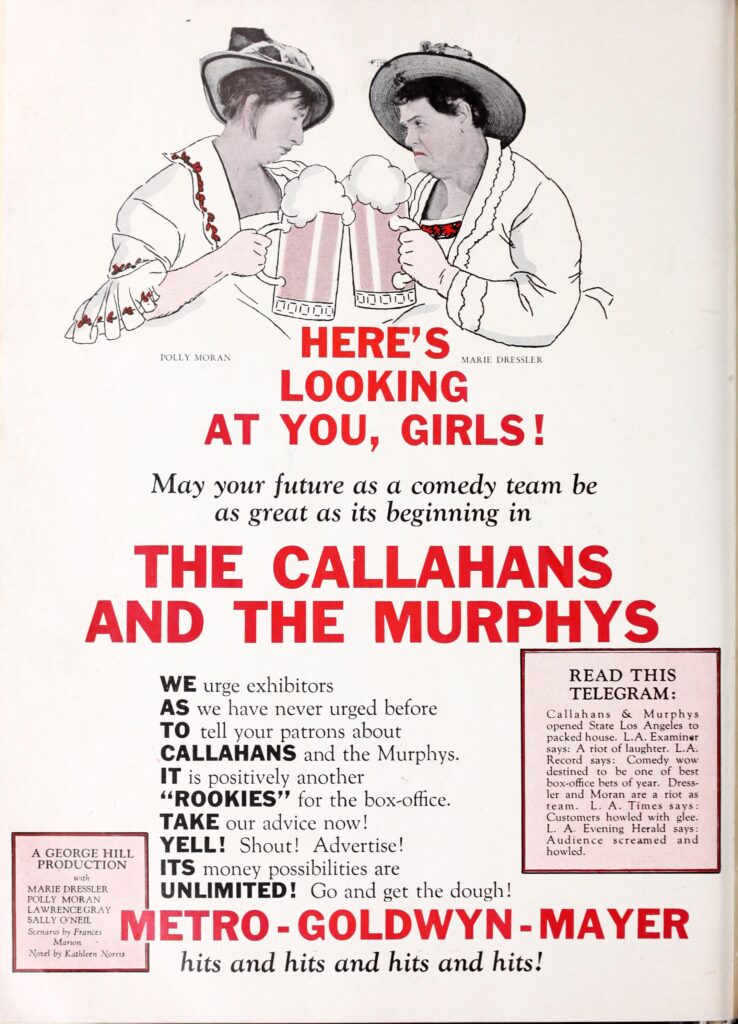

Last year the Irish Film Institute Archive announced the discovery of footage of the (mostly) lost 1927 MGM silent film The Callahans and the Murphys (see IFI Film Eye in HI 32.4, July/Aug. 2024). Screenwriter Frances Marion’s adaptation of Kathleen Norris’s eponymous novel focused on duelling Irish-American matriarchs Annie Callahan (Marie Dressler) and Maggie Murphy (Polly Moran). Mrs Callahan’s daughter Ellen (Sally O’Neil) falls for Mrs Murphy’s son Dan (Lawrence Gray), a bootlegger who strives to free his family from its tenement squalor.

The film marked Dressler’s return to the screen after almost a decade. She found a home and her greatest success at Metro, making nineteen features there before her untimely death, seven with her Callahans co-star Polly Moran. On the negative side, The Callahans and the Murphys ignited a firestorm that proved a key step in bringing about America’s Motion Picture Production Code (a.k.a. the Hays Code) in the 1930s.

In June 1927 MGM submitted its film, running 6,126ft, to the New York Motion Picture Commission. The local censor’s eliminations were minor and the film, released in early July, cleaned up at the box office in New York and Chicago. The film shattered a house record in Portland, Oregon. Small-town cinemas also raked in so much coin that theatre proprietors placed it fourth amongst their highest-grossing MGM rentals of the year, after the Karl Dane–Charles Arthur comedy Rookies, the William Haines sports ‘dramedy’ Slide, Kelly, Slide and the Marion Davies vehicle Tillie the Toiler.

OBJECTIONS

Despite its popularity, the New York Daily News admitted that the film, while very funny, was raucous to the point of vulgarity. Critics in Kansas City went a step further. To them, the uncouth action was an insult to the Irish. A local division of the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH) demanded that the film be withdrawn. Their primary objection was a lengthy sequence at a St Patrick’s Day picnic where Dressler and Moran get sloppy drunk guzzling 2% beer. This, they argued, was not how proper Irish mammies behaved. Worse, when the large-framed Marie Dressler began mugging, her features resembled Thomas Nast’s cartoons that depicted the Irish in simian terms.

That the audience is led to believe that Ellen bears Dan’s child out of wedlock (until matters are cleared up at the end) added to the pearl-clutching. One wag suggested that, owing to the subterfuge, O’Neil should have her Hibernian membership revoked.

Editorials condemning the film began appearing in Irish-American newspapers, most notably the New York Spokesman.

CUTS AND TITLE CHANGES

Hoping to placate the local censors in multiple American states and cities, MGM countered by cutting further. Out went much of a sequence early in the film when Dressler awakes and pulls off a flea—and then pulls back the bedclothes to reveal the culprit, the family dog. She then puts up the Murphy bed, revealing a chamber-pot. Yet the editorials continued, as did demands by multiple Irish-American organisations to pull the film.

MGM tried again, this time working with groups representing the Irish diaspora, including the Los Angeles Council of the American Association for the Recognition of the Irish Republic, the local AOH and the Catholic Theater Guild. The studio implemented a laundry list of cuts in hopes that these organisations would bestow their seal of approval on the project and end the protests elsewhere.

The first title card, establishing the tenement setting, was changed from ‘Goat Alley is a section where a courteous gentleman always takes off his hat before striking a lady’ to ‘This is the story of the Callahans and the Murphys … both of that fast-fading old school of families to whom the world is indebted for the richest and rarest of wholesome fun and humor’. For the picnic scene, little was accomplished by changing ‘They mingled until noon and then they mixed’ to ‘At the picnic everyone was friendly, but the day was young’.

Another establishing title was changed from ‘The morning after the night before’ to simply ‘The next morning’. The studio cut all references to Catholicism. The picnic ceased being held on St Patrick’s Day. Dressler’s running gag of making the sign of the cross—properly when sober, but improperly when drunk, hurried or flustered—ended up on the cutting room floor.

The second half of the drunk scene was eliminated, including a toast to America’s public school system, and shots of the ladies pouring beer down each other’s throats. Footage of the matriarchs thumbing their noses at each other was removed.

Dan’s occupation as a bootlegger was obscured as much as possible. Blanching at all things concerning the human anatomy and bodily functions, the sewer-digger played by Jackie Combs became a plumber, thus granting daughter Monica Murphy (Gertrude Olmstead) a more respectable suitor. A shot of the drunk ladies blowing each other’s noses went the way of all things. Puritanism forced the omission of the film’s best gag. Late in the narrative, the adult children conspire to break the news of the lovers’ elopement and first-born by leaving the infant outside Dressler’s door. Dressler first fears that the infant may be a black Protestant. Jim (Eddie Gribbon) eggs her on by suggesting that the baby may be Jewish. The mystery is resolved when Dressler changes the boy’s diaper. ‘It ain’t no Jew baby’, Dressler declares. In a final effort to save the joke, the titles were softened to ‘Maybe he’s a she’, followed by ‘No—she’s a he alright’. Nothing worked. Out it went.

Although the Association for the Recognition of the Irish Republic remained unhappy with the film as a whole, they acknowledged that the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) had addressed each complaint in good faith. They publicly supported the film, as trimmed, playing in American cinemas. Asking for one additional change, the Daughters of Erin also gave their seal of approval. Their objection remains obscure, but later title omissions include Moran’s taunt ‘If I had a family like yours, I’d sue my husband for damages’ and, during the drunk scene, her complaints against her husband (Tom Lewis)—‘This stuff makes me see double and feel single!’ and ‘I’m just a bundle of nerves tied up to the wrong man’.

Despite the studio’s self-scissoring, local censors still exerted their power. Pennsylvania, Ohio and Kansas bluenoses objected to a bit where Moran, enjoying her short-lived nouveau riche status, shows off her new dog, which she describes as part chow and part bull. Dressler looks over the male dog and declares, ‘I’ll bet I know the part that’s bull’. Ohio and Kansas also clipped a title wherein a doctor at the Hibernian picnic notices the arrival of two more beer trucks. He turns to the nurse and says ‘I think you better order another ambulance’.

SEEKING OPPORTUNITIES TO BE OUTRAGED

Despite MGM’s concessions, Irish-American groups, once riled, began to seek out opportunities to be outraged, not only by The Callahans and the Murphys but also by all films depicting the Irish, including the soon-to-be-released The Life of Reilly (1927, First National), The Cohens and Kellys in Paris (1928, Universal), Irish Hearts (1927, Warner Bros), Finnegan’s Ball (1927, Universal) and the first Dressler–Moran re-teaming at MGM, Bringing Up Father (1928). The veritable feeding frenzy that ensued presaged the cancel culture protests of today.

In August the local Knights of Columbus strong-armed a local cinema in Syracuse, NY, into not screening The Callahans and the Murphys. Protests succeeded in blocking the film in Jersey City, Cincinnati, Bridgeport and Bayonne, as well as return engagements in Boston and Washington DC. Police were called in to restore order at the Loews American at 8th Avenue and 42nd Street in Manhattan when patrons began shouting at the screen in outrage. Protestors threw stink-bombs at the screen at Loew’s Orpheum at 86th and Lexington. Similar protests occurred in Yonkers, NY. Four women faced charges after causing a ruckus when they left a screening at the Loew’s Victoria on 125th Street. A Brooklyn man was also arrested when he stood up in the theatre and shouted that the film was an outrage. In response to the boorish audience behaviour, the Irish Vigilance Committee counter-charged that the police presence at these cinemas incited the riots. Perhaps, but on the last day of the month protesters caused a panic at a screening of Warner Brothers’ Irish Hearts when they threw black paint, vegetables and tear bombs at the screen of the Palace Cinema on 176th Street.

SUPPORTERS

Conversely, the film found some supporters within the Irish-American community. One New Yorker sighed that

‘… it is to be deplored that this moving picture has been viewed as an insult to the Irish. I saw the film, laughed at it and let it go at that. Every “stage Irishman” in the history of the theater might be considered an affront to the Irish, if we were looking for insults. The picture was obviously not intended to offend but to amuse. It is too bad that fact cannot be generally recognized.’

MGM ordered the additional Pennsylvania, Ohio and Kansas cuts to be implemented in New York and, presumably, worldwide. Virtually all mentions of alcohol and fisticuffs were eliminated, as was a sequence built on comic suspense when Moran eats a salad which has a caterpillar on it (she never ate the insect). The gag was repeated in the team’s last film, Prosperity (1932, MGM), without incident. In that film, as in all the later Dressler–Moran pairings, the characters’ ethnic background was never revealed. They were simply ‘Americans’. Had MGM renamed that first film it might survive today.

New York’s state board eventually reached the point where they could not find anything else to cut and advised John T. Kelly of the American Irish Vigilance Committee that the local censors did not have the authority to ban the film outright because it did not violate the state edict as written. (A subsequent push to amend the New York statute to include racial and religious defamation died in committee.) Ultimately, upwards of 15% of the film (about ten minutes from the 65-minute running time) was removed.

All the Philadelphia movie palaces refused to screen the film. MGM winced. When Cardinal Dennis Joseph Dougherty strong-armed the city’s neighbouring cinemas into not screening it either, the studio surrendered. On 5 November MGM announced that it would pull the film from general release in America.

THE ‘DON’TS AND BE CAREFULS’

The film fared no better abroad. Protests, and cuts, followed the film to Australia. A screening in Melbourne spawned a riot wherein several people were injured. Alberta, Canada, banned the film entirely. In late November MGM pulled the film worldwide, pre-empting a planned run in Britain in May 1928. Ultimately, MGM posted a $44k loss for The Callahans and the Murphys.

The immediate fallout from the fracas was the introduction of the ‘Don’ts and Be Carefuls’. The industry-wide guidelines targeted, among other things, ‘racial ridicule’ across the board, not just anti-Irish sentiment. Protests, more from the Catholic Church than from Irish-American groups, continued. In its wake, in 1930, came the first pass at the Production Code, which did not include ‘racial’ guidelines and was hardly enforced. The Church continued to rail against the movies, most notably its unsuccessful boycott against Cecil B. DeMille’s lurid The Sign of the Cross (1932, Paramount). Eventually it would take another woman, Mae West, to foster change. In her first film, Night After Night (Paramount, 1932), when a hatcheck girl marvelled, ‘Goodness, what beautiful diamonds!’, Mae made history by responding, ‘Goodness had nothing to do with it, dearie’. In her second outing, She Done Him Wrong (Paramount, 1933), Mae growled out the naughty saloon ballad ‘Frankie and Johnnie’ and invited Cary Grant to ‘come up and see me sometime’. But it was her third film, I’m No Angel (Paramount, 1933), that made the bluenoses apoplectic. In addition to ribald one-liners like ‘When I’m good, I’m very good—but when I’m bad, I’m better’, Mae fraternised with her African-American help and, worst of all, easily dominated every man who crossed her path, even in court.

In 1934 Archbishop John T. McNicholas of Cincinnati founded the National Legion of Decency, but it was a total boycott of cinema attendance directed by Cardinal Dougherty that did the trick. Beginning on 1 July 1934, all films exhibited in the US required an MPPDA certificate of approval. After more than a year of boycotts, Dougherty declared the situation improved and lifted his ban. American films would remain squeaky clean for another third of a century.

For decades The Callahans and the Murphys was considered lost. Then, in the early 2000s, two short 16mm clips, amounting to less than 10% of the total film, found their way into film archives. The first clip resides in the Library of Congress. At just over two minutes, it preserves the initial contretemps between the matriarchs over a sugar bowl. The clip is easy to find on YouTube.

The second was also donated in the early 2000s, this time to the Irish Film Institute. Mislabelled Irish Picnic, archivists only discovered what they had in 2023. Running shy of four minutes, the clip offers a tantalising glimpse of the infamous picnic scene and the mothers guzzling beer.

One mystery remains: The Callahans and the Murphys does not appear to have been screened in Ireland before the ban came down. Under what circumstances was this clip assembled, and by whom? Might there be more footage out there somewhere?

Film and theatre historian Christopher S. Connelly is the author of Helen Morgan: the original torch singer and Ziegfeld’s last star (University Press of Kentucky, 2024).

Further reading

M.A. Kibler, Censoring racial ridicule (Chapel Hill NC, 2015).