by Raymond Gillespie

Between 1580 and 1640 about 370,000 Englishmen and 100,000 Scots left home and family to make their fortune outside their native land. Rising population and demand for increasingly expensive land along with diminishing opportunities in the church or the law for younger sons made self-imposed exile an inescapable fate for many. Some, such as those from the east coast of Scotland, went to continental Europe as mercenaries in the armies of the antagonists in the Thirty Years War. From east and south-west England, others fired by religious zeal travelled west to create a new England on the north-east coast of newly discovered America. Others from the same areas were lured to this new and exotic land by stories of fabulous fortunes to be made in the more commercially minded colony of Virginia. If one did not have the stomach or the funds for a long sea journey or the nerve required of a mercenary soldier, a third option for fortune seekers opened up in the course of the sixteenth century: Ireland. Ireland did not have the lure of the exotic. Its inhabitants had been trading with and emigrating to England and Scotland throughout the middle ages. From western England or Scotland, it was only a short sea journey to the east coast of Ireland.

The eclipse of Kildare

The opening up of Ireland for colonisation came about almost by accident. Throughout the sixteenth century the Dublin administration, increasingly after 1534 in the hands of New English officials rather than the Old English (descendants of the Anglo- Norman settlers), was faced with a twin problem. First, they wanted to eliminate the fragmented political authority which bedevilled sixteenth-century Ireland. To achieve this, the near autonomous, indigenous Irish lordships had to be bound together into what both Old and New English administrators called a ‘commonwealth’, held together by common bonds and assumptions about language, authority and the law based on English models. Such a drastic change could not be implemented overnight. These were long term aims. The second problem was a more immediate. How could the borders of the Pale, the area of English authority, be protected while these more ambitious changes were effected? Before 1534 the Earls of Kildare, as chief governors of Ireland, could rely on treaties, marriage connections and their own powers as overlords to ensure stability. With the eclipse of the Earls of Kildare from government after 1534, new techniques had to be evolved.

Garrisons

The first solution to this immediate problem was a simple one: strategically placed garrisons. Garrisons, however, required to be paid and the Irish exchequer was in no position to provide such funding. In 1548 a solution presented itself. The marshal of the army, Nicholas Bagenal, was granted the lands of the dissolved

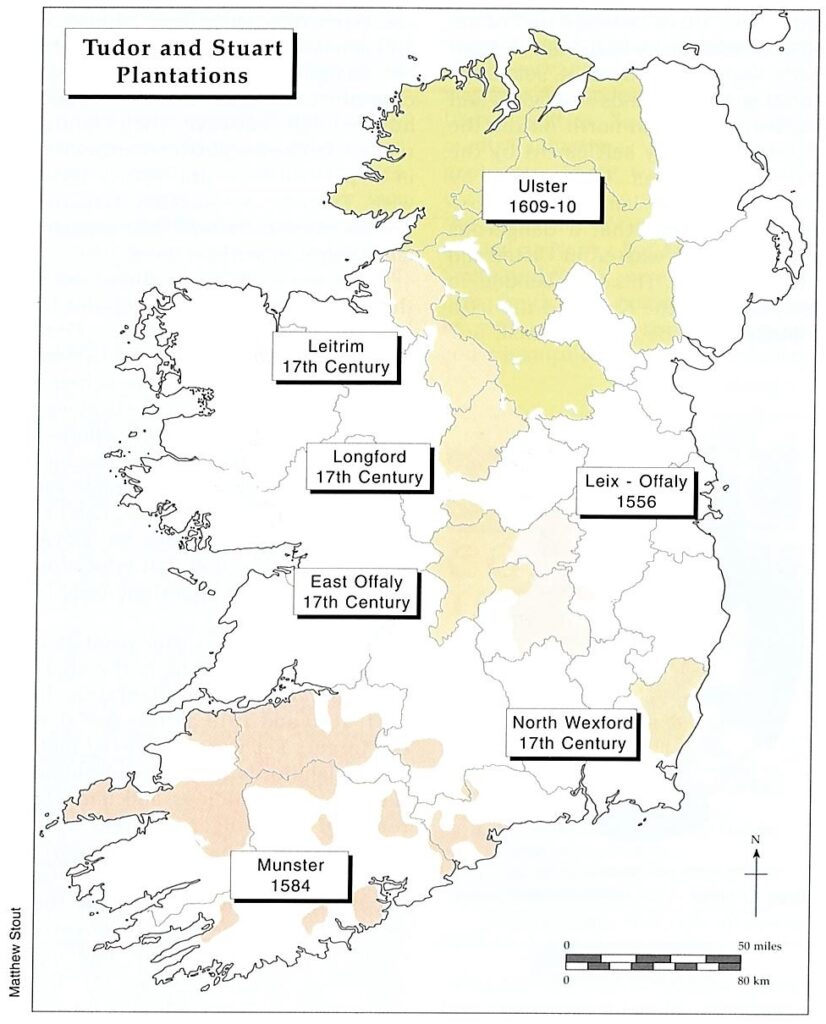

monastic house at Newry with the injunction that he establish a fort there to protect the northern part of the Pale against incursions from Ulster. To make his lands economically productive Bagenal brought settlers from his estates in Wales. Such grants were not formal plantations but were haphazard solutions to the defence problem since they relied on the crown’s ability to prove title to land before grants were made. The best opportunity presented itself in 1547 when a local rising of the O’Connors, O’Mores and O’Dempseys led to their land being confiscated. Initial attempts to redistribute this to the ‘King’s loyal subjects’ met with little success despite offers from individuals, such as Edward Walshe, to organise private settlements. It was 1557 before a more systematic approach was applied to the area. Under Mary, Leix and Offaly were transformed into Queen’s and King’s counties (after Mary and Philip) and set aside for a settlement of soldiers and others from within the Pale and England. The intention was to provide security for the western edge of the Pale and also generate royal income through rents and other payments to the Irish exchequer.

The idea of cheap defence by contracting the work to private enterprise immediately proved a success in the eyes of the government. It was used frequently in the sixteenth century. In 1571 and 1572, for instance, Sir Thomas Smith and the Earl of Essex were granted large parts of east Ulster, to which crown title had been conveniently provided by the attainder of Shane O’Neill. The aim was to establish private settlements which would provide bulwarks against highland Scots, whose recent arrival in large numbers was feared as a destabilising factor in Ulster politics. Such private settlements sometimes caused serious problems. There was no guarantee that a private venture could supply the necessary security. Bagenal’s settlement

succeeded but those of Smith and Essex were miserable failures, Smith’s son being killed. To confer military roles on these settlements could institutionalise violence as happened in the midlands. There soldiers found it profitable to harass the native Irish and to maintain a large military presence for which captains could draw allowances. Such settlements simply replaced over-mighty and violent English ones.

The Munster plantation

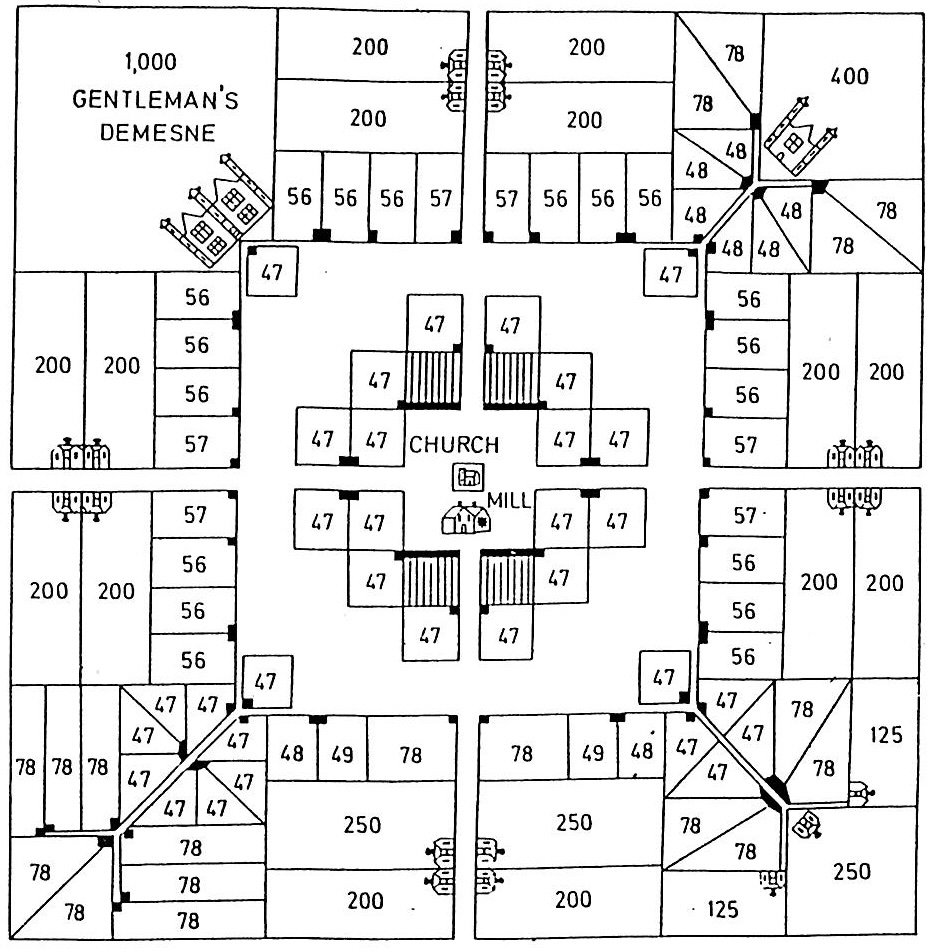

Military settlements might well be a cheap way of providing security in the short term but they did little to promote the longer term aim of creating an English-style commonwealth in Ireland. That needed more concerted action especially since the Catholic Old English, who had previously shared the ideal, were increasingly alienated by growing religious differences with the Protestant New English government in Dublin. The opportunity for such action presented itself in November 1583 when the Earl of Desmond, in rebellion since 1579, was surprised and decapitated in a glen near Tralee. A rebel under the common law, his lands had been declared forfeit almost four years earlier. The end of the war provided an opportunity for government to decide what was to be done with this large portion of Munster. It took them two years and a large scale survey of the province to decide. The moving force behind the scheme which emerged in 1585 was almost certainly Elizabeth’s principal secretary of state, Lord Burghley. It was 1586 before the details of the scheme were finalised and it was soon apparent that this was unlike anything else that had been tried in Ireland. It was nothing less than social engineering aimed primarily not at defence but to re-create the world of south-east England in southern Ireland. An estate system was to be formed by making grants ranging from 4,000 to 12,000 acres to thirty-five English landlords. They were to be the agents who would introduce English lifestyles by building villages and settling on their lands within seven years freeholders, holders of fee farm grants, copyholders and cottagers. Each estate was intended to have ninety households by 1593. The scheme introduced the English law of landlord and tenant to regulate the settlement. The allocations of the different tenures to the settlers was not random. It was designed to produce a social hierarchy with powerful freeholders at the top and cottagers, with no security of tenure, at the bottom. This hierarchy also ensured that landlords would not become over-powerful as the English government felt native Irish lords had done. The landlords were also to introduce English- style agriculture based on grain growing. This was labour-intensive and would promote stable settlement, replacing the highly mobile cattle-raising favoured by the native Irish.

Ranchers and profiters

The scheme was a triumph for central government planning but it was a disaster for central government administration. The targets for settlers were not achieved by 1592 and landlords were less effective than it was hoped in building villages and introducing agricultural change. London may have had good social reasons to think that wheat would grow in Munster but the settlers had the evidence of climate and soils that it did not. Instead they took to raising native Irish breeds of cattle. Most settlers had enough problems in getting themselves and their tenants to Munster without worrying about English breeds of livestock as well. Perhaps the most serious problem lay in the selection of landlords. Many did not have the cash resources which were necessary to undertake the sort of plans the government had in mind for them. While London considered expenditure of £2,500 on each estate necessary, few claimed to have spent more than £1,000 and most spent less.

If government was dissatisfied at the short-term results of plantation the settlers were delighted. Landlords had acquired estates at a nominal cost and tenants who moved from England went from a land of high rents and scarce resources to a world of low rents and abundant land. For those wishing to sell land there was a ready market. Hovering on the edge of that market was a young Richard Boyle, ready to acquire land in Munster by legitimate and more dubious means so that by the 1630s his estate in Munster would make him one of the richest men in the British Isles. Government may well have been too hasty in expecting returns from Munster in less than ten years. The experience of the early seventeenth century was that the plantation scheme would go a long way to meeting its aims but that would take longer than most contemporaries expected.

The Ulster plantation

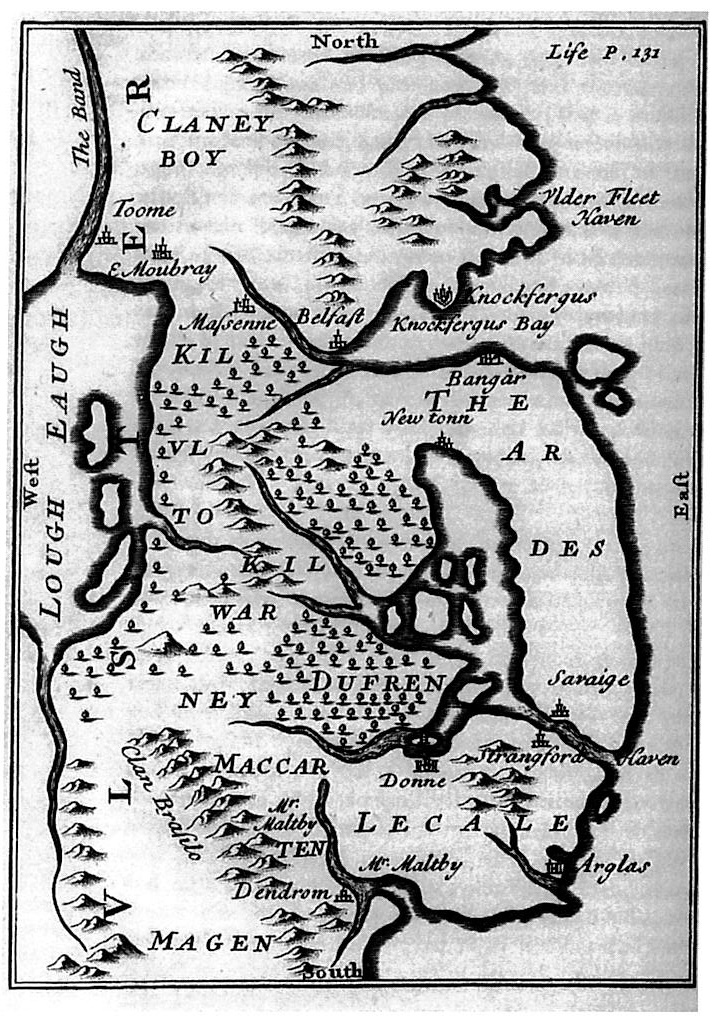

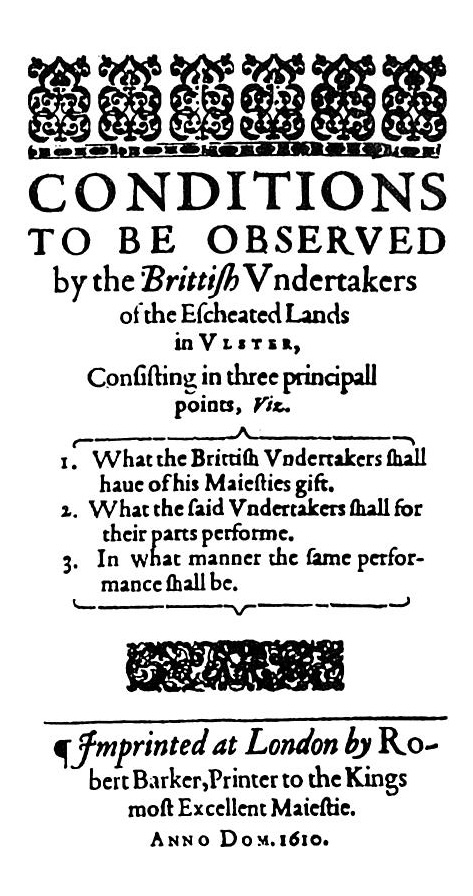

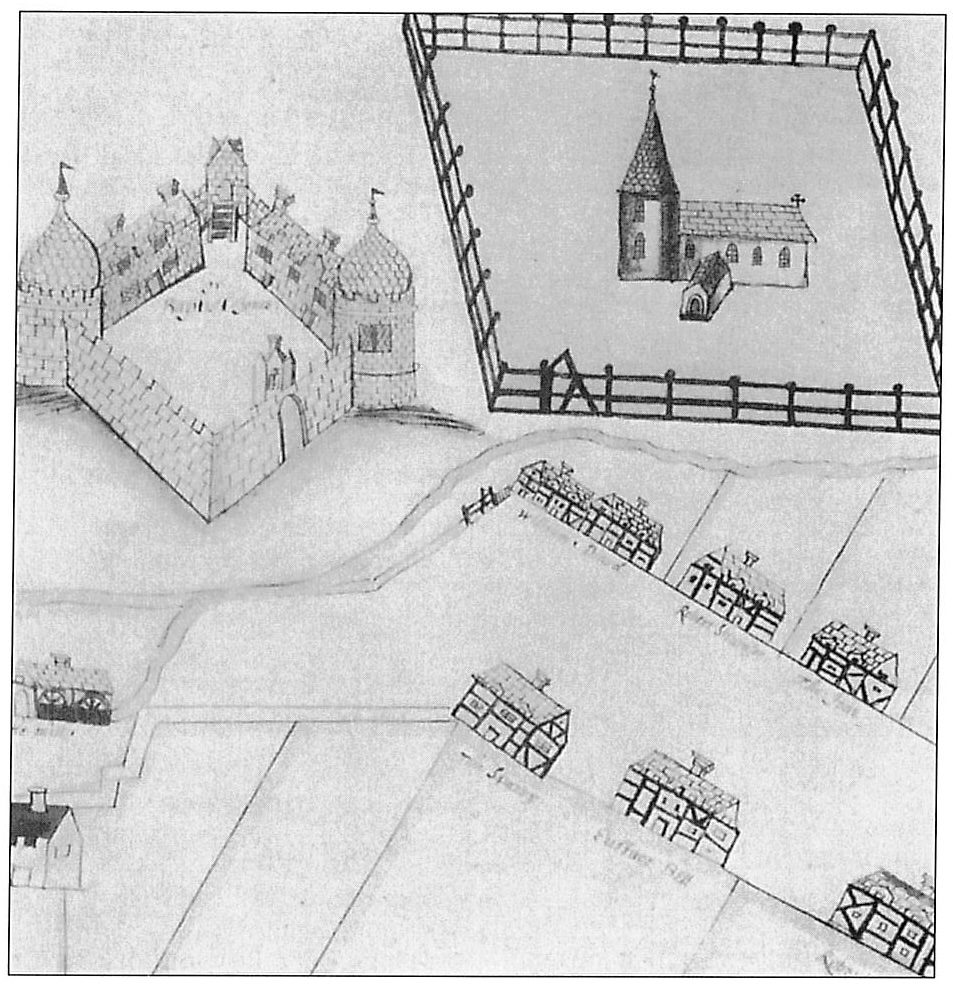

In 1593 most officials were disappointed with the results of the Munster scheme but further consideration of the problem and the invention of excuses and recriminations were cut short by a redirection of government energies necessitated by the outbreak of the Nine Years War in 1594. However, the government had learnt a salutary lesson about the problems associated with plantations and they were reluctant to become involved in another scheme. At the end of the Nine Years War in 1603 they were prepared to offer Hugh O’Neill, earl of Tyrone, an advantageous peace rather than confiscate his lands as a traitor and risk repeating the Munster debacle. Their hands, however, were forced when in September 1607 O’Neill and his main followers unexpectedly left Ulster for continental Europe never to return. The government confiscated (or escheated) their lands comprising the modern counties of Armagh, Tyrone, Fermanagh, Londonderry, Cavan and Donegal. Antrim and Down were not part of the official scheme although there native Irish lords, burdened by debt, sold large portions of their lands to English and Scottish settlers and in north Antrim the sixteenth century settlement by the MacDonnells was legitimated by crown grants of land. A dangerous power vacuum existed in Ulster which it was necessary to fill. As with Munster twenty years earlier there was no shortage of suggestions but most of these, including that of the lord deputy, Arthur Chichester, were swept aside. London, this time in the person of the King and the Irish committee of the Privy Council, prepared a scheme which appeared in 1609 and was slightly modified in the next year. The scheme certainly shows influences from and reactions to the Munster plantation and influences from an earlier attempt by James I to plant the island of Lewis in Scotland. Like Munster, land was to be allocated to landlords (Scottish and English, reflecting the union of the crowns in 1603) but in much smaller proportions: 2000, 1500 and 1000 acres or between a sixth and a quarter of a Munster land grant. It was felt that these were more manageable for men of modest means. The problem of shortage of capital for development was also tackled in a new way. The entire county of Coleraine was set aside for settlement not by individuals but by that new invention of sixteenth-century entrepreneurs – a joint stock company. The shareholders, and providers of capital, were to be the twelve London livery companies who set up the Irish Society to manage their asset, newly renamed county Londonderry. Each company received one estate which it was to develop.

Reshaping the social world

The Ulster plantation scheme also contained provisions for the reshaping of the social world. The number and types of tenants were stipulated for each landlord and land was also to be assigned to the established church. Landlords were to build houses and improve their lands, removing their native Irish tenants within a specified time and replacing them with English or Scottish tenants. Towns were to be built and artisans encouraged to settle in them.

There were two innovations over the Munster scheme which point to slightly changed thinking. First native Irishmen were to be among the grantees in the scheme and officially about a fifth of the land was eventually granted to them whereas in Munster all Irish had been excluded. Secondly, provision was made for schools in the Ulster scheme with land in each county being set aside for ‘Royal schools’. This seems to indicate that there was an intention that education would be an important agent of social change.

Like Munster the Ulster scheme in the short term was below expectations. Surveys of the plantation in 1611, 1615 and 1619 all revealed that the targets set for the plantation were not being met. Settler landlords had not completed the required buildings and had not removed the native Irish from their estates. Towns were poorly developed and many existed only on paper. Most importantly, for the perspective of the London government, the new settlement had not generated much revenue for the exchequer. A major enquiry on the state of the plantations, and the government of Ireland generally, was undertaken in 1622 which resulted in threats of confiscation of land from those who had not fulfilled the stipulations of the plantation. Indeed it was this threat which made some of the Ulster planters uneasy bedfellows with the Old English in demanding security of tenure during the episode of the Graces in the late 1620s. The London companies suffered most severely, being fined heavily in Star Chamber in the late 1630s for failing to carry out their obligations.

Success

Judged by the aims of the settlers, the Ulster settlement was more successful. They had acquired at almost no cost substantial estates although many did not have the resources to develop those lands. Most were younger sons, government officials or those who hoped the Ulster adventure would reverse their declining fortunes at home. They had to develop their lands using the rents from their new estates which took time to accumulate. Indeed their reluctance to remove the native Irish from the land can be explained by the high rents paid by those Irish. Some landowners may well have found the terms of the formal plantation scheme inhibiting. Their counterparts in Antrim and Down proved more willing to encourage settlers to their lands and the settlement outside the formal scheme was much more successful than in other parts of Ulster.

In economic terms the plantation was a major triumph. The introduction of many new settlers, probably 15,000 adult males by 1630, swelled the labour force in Ulster, which had been sparsely populated in the late sixteenth century. Output of cattle and oats rose enormously, so much so that Scotland had to impose limits on the import of Ulster grain fearing that it would drive down prices in Scotland. The effectiveness of the various plantation schemes in promoting economic change has been the subject of some debate among historians. Nicholas Canny has argued that technological change in Munster made it superior to Ulster but Raymond Gillespie had pointed to the greater output of the Ulster economy in the early seventeenth century as evidence of much faster change than might otherwise be thought.

The Ulster plantation was also successful in one other way: it neutralised resistance from the indigenous Irish. For almost thirty years after the plantation there was no serious trouble in Ulster, with the exception of an abortive conspiracy in 1615 which was related to factors other than the plantation. Many of those who were disaffected had gone as mercenary soldiers to Europe or to the Irish colleges, especially at Louvain, as clergy. A generation was to pass before the rebellion of 1641 caused disruption. By then the reasons for discontent were to be found in the circumstances of the late 1630s rather than the plantation of thirty years earlier. Indeed the planners of that rising had been beneficiaries of the scheme rather than its victims.

From plantation to redistribution

By 1615 the great age of plantation was over. There were other schemes in the early part of the seventeenth century which were described as plantations, as in Wexford, Leitrim, Longford and other areas of the Irish midlands, yet these were different from the Munster and Ulster schemes. They were essentially redistributions of land following the establishment of crown title. The newly created landlords in these counties, with a few exceptions such as Lord Granard in Longford, did not come from England or Scotland. They were drawn from the ranks of the Dublin administration and the land grants were often a reward for loyal service. Grantees in Longford, for instance, included Francis Edgeworth, a clerk in Chancery, who founded a dynasty which included the authoress Maria. The allocations to native Irish varied from scheme to scheme with about half of Longford, the most generous scheme, allocated to them. In the main these new settlers were not tied down with the detailed conditions which had been stipulated in Munster and Ulster and in particular they were not bound to introduce settlers as tenants on their estates. Scots and English tenants did feature in these areas but they came from Ulster where, by the 1620s and 1630s, opportunities were becoming less attractive while the new settlements offered good deals in land. It was a process of colonial spread rather than formal plantation which brought these settlers to their new homes.

There was one further abortive attempt by Lord Deputy Wentworth to institute a plantation of Connacht in the 1630s. Stiff opposition to the scheme by a politically articulate group in the west meant that progress was so slow and the plan was still on the drawing board when Wentworth fell from power and was beheaded on 12 May 1641. Just as the execution of the earl of Desmond marked the beginnings of formal plantation schemes so the decapitation of Wentworth marked the end of such schemes. No one again produced formal plantation schemes for Ireland. Unlike the early seventeenth century experience of rising population and fears of poverty the English experience in the late seventeenth century was of stagnant or falling population. Government became concerned to ensure that people stayed at home to promote the growth of the economy rather than go abroad. English migration to late seventeenth-century Ireland all but ceased. Only the Scots, disturbed by the Covenanter troubles of the 1670s and the harvest crises of the 1690s continued to come to Ulster in large numbers to rebuild the settlement shattered by the 1641 rising and its aftermath. There was, of course, land redistribution in the late seventeenth-century. During the 1650s and at the Restoration and again after the Williamite revolution land passed in large quantities from protestant to Catholic. It was these later events which made such a dramatic impact on the Catholic ownership of land, shrinking it from 61 per cent in 1641 to 22 per cent in 1688 and after the Williamite settlement to 15 per cent in 1703. Yet these were not plantations in the early seventeenth century sense. They were the division of the spoils of war by the victors at the expense of the vanquished. Armies had to be paid and Irish land was the cheapest way of rewarding loyalty and meeting soldiers arrears. None of the new settlers was bound to introduce settlers, make any improvements in their land or even give any thought to its defence.

Conclusion

The plantations of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries were powerful forces in introducing change into Irish society. They created an ordered network of estates which was to survive into the nineteenth century and their landlords were to be the main agents of economic change and social development into this century. The requirements to build and introduce settlers affected almost every aspect of life from dialect through agricultural practices to social customs. In short they gave Ulster its Scottish character and Munster its English tone and in so doing both reinforced and changed the nature of Irish regional identities. To try to understand modern Ireland without investigating the plantation process at all levels is like playing hurling without a slitter.

Raymond Gillespie lectures in history at St Patrick’s College, Maynooth.

Further Reading:

R. Gillespie, ‘Explorers, exploiters and entrepreneurs: early modern Ireland in its context’ in B.J. Graham & L.J. Proudfoot (eds), An historical geography of Ireland (London, 1993).

R. Gillespie, The transformation of the Irish economy (Dundalk, 1991).

M MacCarthy Morrogh. The Munster plantation (Oxford, 1986).

P. Robinson, The plantation of Ulster (Dublin 1984).