by Louis Cullen

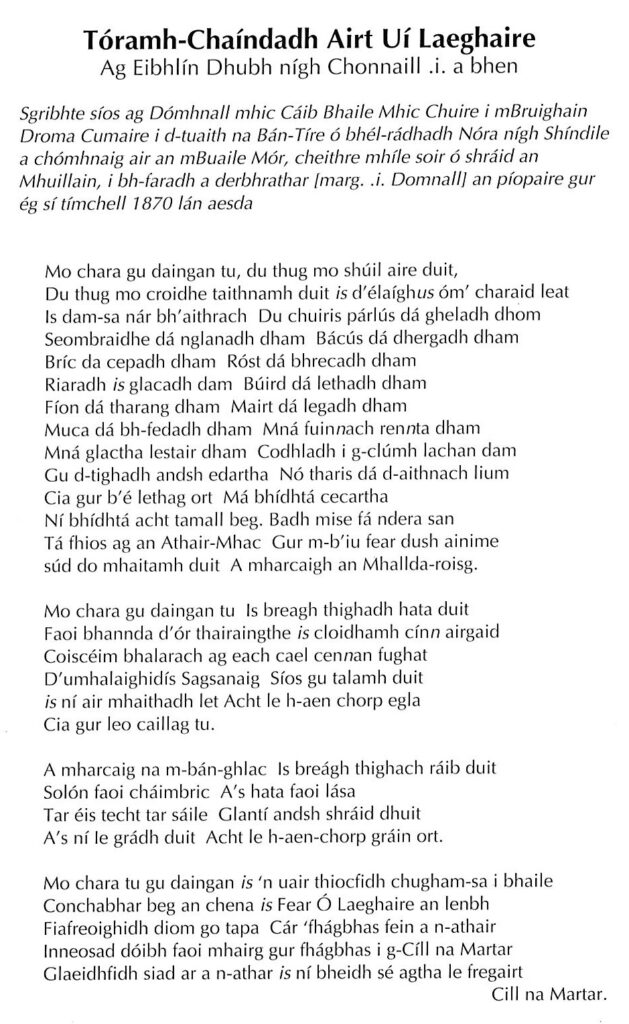

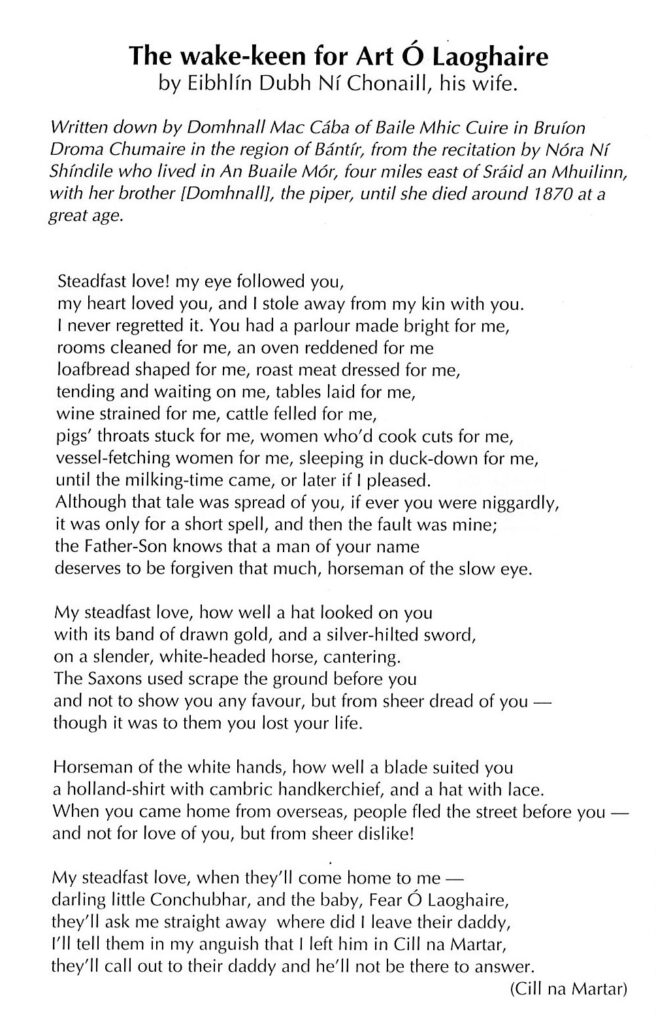

The Caoineadh Airt Uí Laoire is a powerful composition; the theme of Arthur O’Leary refusing to sell his horse in accordance with the terms of the celebrated penal law which required a Catholic to sell a horse if offered £5 by a magistrate, and later losing his life in a confrontation in 1773, has a tragic appeal.

The poem acquired a large audience in the decades from the 1890s. But despite its being well-known for several generations, changes in the school syllabus mean that knowledge of it among the young has waned sharply in recent years.

While most Irish poetry survives in manuscripts taken down in the eighteenth century itself, the Caoineadh Airt Uí Laoghaire survives in no manuscript contemporary with the events in it. Its earliest known manuscript source is much later. There are, however, two oblique contemporary references to it. Edmund Burke may have been aware of the event and Arthur Young was briefed for his Irish tour by him. In describing a tense interview with Baron Anthony Foster in 1776 which directly touched on firearms, Young quoted Burke on freedom from arbitrary law enforcement. In Eoin Rua O Súilleabháin’s poem, A fhile ghéir chliste, faint re-echoes of the events occur in the alliteration within the poem of the names of two of the families, Townsend and Tonson, who were the most prominent of O’Leary’s opponents.

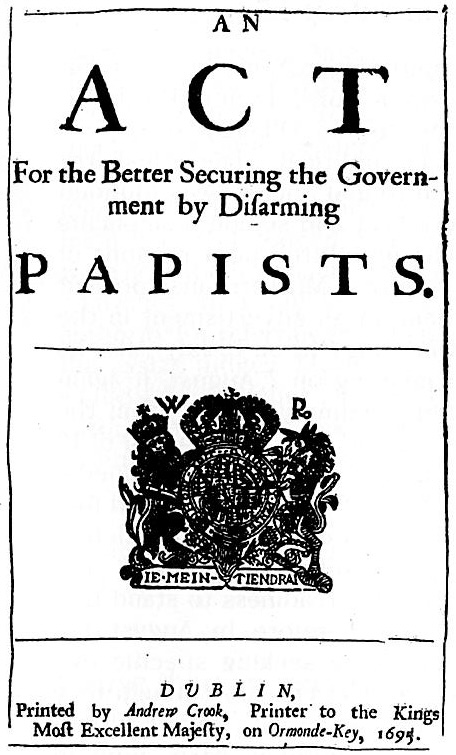

Legal program

Catholics were in a novel position from late 1766. The attempted legal pogrom in Munster (on the pretext of suppressing Whiteboy activity) which had taken the life of Father Nicholas Sheehy and three minor gentlemen in 1766, was halted within the year. The collapse of the case against forty other propertied Catholics, largely through Edmund Burke’s masterful organisation of the defence team and background lobbying, may have led some like O’Leary to challenge the local establishment recklessly. It was probably fear in the wake of the traumatic year1766 that accounted for the opposition of the Derrynane O’Connell family to the 1767 marriage of a daughter, Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill, to O’Leary, an assertive young army officer just returned from overseas. It is reflected too in the Baldwin-O’Leary tension that briefly surfaces in the poem: James Baldwin, who had married a sister of Eibhlín Dubh, may have shared the misgivings of other Baldwins who aligned themselves against O’Leary in 1771.

O’Leary’s return in 1767 occurred at that decisive moment when old fears from the past and a new sense that Catholics could successfully be assertive were simultaneously in the air. Just as the Sheehy episode in 1766 marked the termination of an era of political persecution in Tipperary and north Cork, so too can the O’Leary episode in 1773 be regarded as a dénouement to tensions in west Cork. The reluctance to proceed against O’Leary at the assizes after the fairly routine step of lodging bills of indictment with the grand jury in August 1771 shows how times had changed: within a major county, the anti-Catholic faction was hesitant and could no longer count on general backing. A bill of indictment required the oaths of at least twelve grand jurors, but became effective only if a majority of jurors in full session returned it as a ‘true bill’. In some respects the two periods mark the point at which more virulent forms of local anti-Catholicism became a discredited political commodity.

O’Leary’s horse demanded for £5

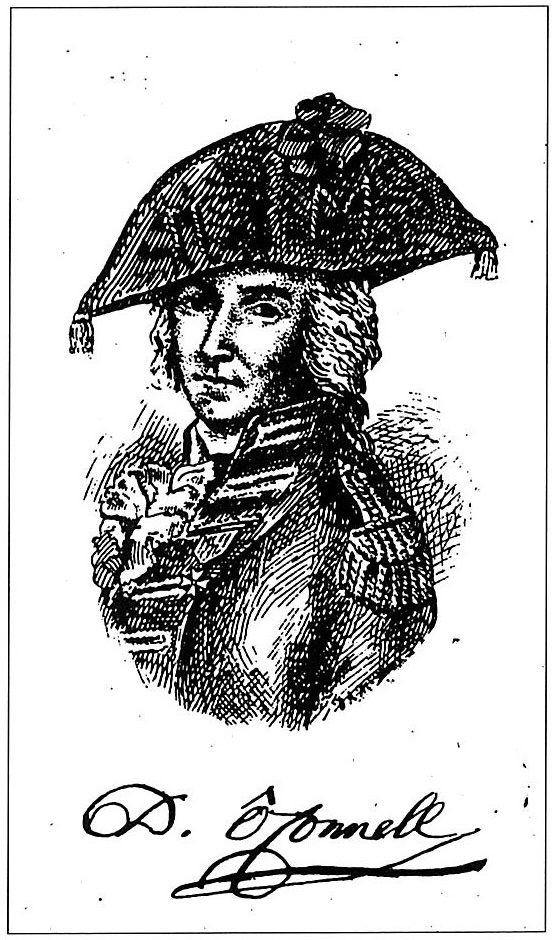

Despite suggestions of rivalry in love or in horse racing, the background to the O’Leary story was entirely political. The Muskerry Constitutional Society was founded in July 1771 and sought ‘complaints which any injured poor persons of the barony of Muskerry may present to them’ in an advertisment in the Cork Evening Post on 18 July. After its next meeting on 7 August, it again sought ‘communications’ from the public in the Cork Evening Post of 19 August. The same issue contained a reply from O’Leary which stated that he had been charged ‘with different crimes by different persons’, and declared his readiness to stand trial on them. Therefore, by August, the Society were seeking specific evidence against O’Leary (though they may not necessarily have had him directly in mind in early July) in order to substantiate the charges in bills they were preparing. Significantly, the dispute with the magistrate Abraham Morris occurred on 13 July, according to a later Morris statement of 7 October, which again appeared in the Cork Evening Post. Thus the founding of the Society with the politically resonant term ‘Constitutional’ in its name and the O’Leary intervention with Morris occurred in the month preceding the assizes. According to O’Leary’s later declaration, he had gone ‘to apply to Mr Morris as magistrate relative to some law proceedings’ on 13 July. O’Leary probably had then made himself obnoxious by his interest in some cases pending at the Assizes in a county already notorious for its magistrates’ readiness to keep the penal laws alive. Morris, provoked by O’Leary’s assertiveness and intending to put him in his place, demanded his horse in exchange for £5. Significantly, O’Leary’s brashness seems to be hinted at in the reaction two years later on receipt of news of his death by Daniel O’Connell, uncle to Eibhlín Dubh, grand uncle of the Liberator and an officer in French service. He had met O’Leary in Ireland before his death, and recalled that ‘the short acquaintance I had with him gave me a more favourable opinion than I had at first conceived of him’.

Seizure of a gun

O’Leary’s alleged seizure of a gun from Morris was one of the charges against him in 1771. Morris, a near-neighbour of O’Leary’s in the vicinity of Macroom, was a supporter of the political interest headed by the Earl of Shannon, County Cork’s premier grandee, which had driven the anti-Catholic campaign both locally in the 1760s and in the 1762 and 1764 sessions in parliament. Morris was not high sheriff in any year in the early 1770s, contrary to what is said in modern accounts. However, he had been high sheriff in 1760, and his nephew was to be high sheriff in 1782 and Shannonite MP in the 1790s.

Morris’s and O’Leary’s statements and counter statements feature the question of a gun. According to O’Leary, Morris and a servant pursued him bearing firearms; the servant discharged a gun which O’Leary then seized and surrendered to another magistrate.

According to Morris, O’Leary seized the gun, and made off with it. The import of this was grave. O’Leary had violated the penal laws by even holding a gun; more seriously he had allegedly acquired it by force in the presence of Morris, a magistrate. Morris’s offer of a reward for the apprehension of O’Leary on 7 October 1771 was followed by a reply by O’Leary dated 19 October, both published in the Cork Evening Post.

The events of July and August 1771 were heavily influenced by the knowledge that the summer assizes were due to begin on 23 August. The Muskerry Constitutional Society’s declaration of 15 August 1771 was signed among others by five clergymen, three Townsends (two of them clergymen), and Sir John Conway Colthurst, a rather cretinous parliamentary follower of Lord Shannon, of whom it was noted in a 1773 list of MPs that ‘he will always obey him (Shannon), a mere paltry fellow’. The fact that the events did not attract straightforward reporting but were communicated by advertisements suggests the conduct of a highly personalised vendetta on both sides. If there had been a hearing at the assizes on foot of ‘true bills’, Morris would have referred to it in his statement in the autumn. Morris and the Muskery Constitutional Society could only claim that bills of indictment had been lodged. While these were potentially damaging to a man’s character, they did not constitute authority for referring the charges to the assize judges. Moreover, there would be no further assizes till the spring. In offering rewards in the autumn, Morris and the Muskerry Constitutional Society seem to have gone beyond strictly legal limits in attempting to initiate further action well ahead of the March assizes of 1772.

Worse than an outlaw

The case had a number of intriguing features. O’Leary was never technically outlawed; Daniel O’Connell, the Liberator, was certainly wrong in claiming in 1834 that O’Leary was the last man outlawed in Ireland. In a sense the actual situation was even worse: if not outlawed under due legal process, O’Leary was subjected to an irregular attempt at outlawry not by a grand jury but by a tiny coterie, a step beyond the powers of individual magistrates. While bills of indictment had apparently been lodged, O’Leary repeated his August offer to stand trial in October 1771. This offer is crucial to understanding events at that time. The charge that O’Leary was ‘under arms and on his keeping’ did not rest on a grand jury verdict, but was fabricated by Morris and the Society in October. As the law stood, a Catholic carrying arms would in itself warrant action by a magistrate because he would be committing an offence at the time of arrest. In the absence of a ‘true bill’ to answer, the attempt to represent O’Leary as an outlaw went both beyond the facts and the magistrates’ legal competence. Morris’s action in October was at best on the margins of legality.

This situation produced a legal stalemate. Morris and the Muskerry Society were unable to turn their bills of indictment into ‘true bills’, while on the other hand O’Leary lived under the shadow of a trial or of arrest. While still free to come and go, O’Leary must have been apprehensive that Morris or others would attempt to arrest him on flimsy authority. He remained at liberty for two years, coming and going with impunity, and no effort was made to arraign him in court. There were no known legal developments at either the spring or summer assizes in 1772 or in the early spring of 1773. In 1773 the spring assizes in Cork began on 22 March and ended on 29 March. On 15 April, Daniel O’Connell commented that he was ‘glad to hear our friend Arthur arrived safe’ implying that nothing untoward had occurred at the assizes. If O’Leary was in Cork City at the time of the assizes, he may have been there either to answer a case if ‘true bills’ emerged, or else to taunt his enemies for failing to get the grand jury support.

O’Leary shot dead

Relations between Morris and O’Leary however detiorated to a new nadir, with either party (we do not which) precipating the final tragedy. It is vitally important at this juncture to appreciate that Morris was not the high sheriff. Very probably, the proceedings at the spring assizes had been unseemly, and Morris may have kept the charges alive. O’Leary’s death in 1773 was, however, in part of his own making: he took the initiative in seeking Morris out, and the folklore suggests that his intention was to kill him. In the event O’Leary himself was shot dead in suspicious circumstances by soldiers accompanying Morris. A coroner’s jury in June 1773 found Morris guilty of murder.

O’Leary had obviously not lacked backing. In July 1773 a large string of political notables offered rewards for discovery of the person or persons who fired three shots at Morris at the window of his lodgings in Cork, but this was exclusively from the Shannon interest. Others, notably the powerful gentry interest of north Cork and the parliamentary members for the city, were conspicuously absent from the list.

The furore over the shots allegedly fired at Morris in July was not generated by the need to protect his person from physical assault than to mount a legal defence (there is no evidence that Morris was seriously at risk, and even less evidence for the 1830s view that O’Leary’s brother had fired the shots). Urgency was imparted by the fact that the assizes were due to begin on 28 August. The coroner’s inquest had already decided that O’Leary had been murdered. Ironically whereas O’Leary had long faced the risk of a trial at the assizes, it was Morris who was finally tried, and on the much more serious charge of murder. In July the outlook for Morris did not seem good. He was stigmatised as the leading figure in a strange vendetta which had never enjoyed the backing of ‘true bills’ of indictment and the coroner’s jury’s decision in June was very damaging. Accordingly it was necessary for Morris’s defence to represent the alleged attempt on his life as serious; by deeming that rewards were necessary at national as well as local level, then the murder case, it could be argued, was not a dispute in which a magistrate had behaved badly but one in which he had lived under long-standing murderous threat. These considerations would influence the opinion of many attending the assizes, and could well weigh forcibly on the mind of a petty jury selected for the trial, especially if the full weight of the Shannon interest was engaged in lobbying. These convoluted matters finally came to an assizes hearing in September 1773 when Morris was tried . It was a singular ocasion as the accused was a magistrate. His final acquittal, given pressure from the Shannon faction, could plausibly suggest improprieties in the court proceedings. The suggestion in the poem of the widow’s intention to seek justice in London is not irrelevant: the case against O’Leary had never been backed by the full grand jury and the notorious rewards offered in October 1771 were unwarranted, arising not from grand jury true bills of indictment, but from a novel twist of continued law breaking introduced by Morris and his partisans.

A living popular commentary

The Caoineadh Airt Uí Laoghaire was regarded by Bromwich as ‘the climax of a long tradition of keening’. However, all its compelling characteristics — its taut composition, its powerful emotional appeal which led to its circulation (perhaps in manuscript as well as in fragmented and constantly changing oral versions) and its popularity — make more complete sense if the poem is securely located in a precise political context. With a death in 1773, a murder attempt on O’Leary’s own killer, and a murder trial of a magistrate (himself a former high sheriff), the events were extraordinary. The widow may have composed little or any of the elegy and certainly much of it was not written at the time of O’Leary’s death. It is more a living popular commentary, responding to issues generated by a traumatic sequence of events in local life.

Interest in the poem’s content revived for very unpoetic reasons in the new outburst of political emotion in Cork triggered by the Emancipation struggle in the 1820s. The text seems to have been withheld from Crofton Croker, the politically obnoxious author of equally obnoxious works in 1824 and1844 which dealt with the keen and various literary and political issues. At this stage, the fullest version of the ‘keen’ was written down from a folk source (probably on a single occasion, not as is usually suggested at two dates, one earlier, the other much later). While Croker’s intervention saved the Caoineadh Airt Uí Laoire for posterity he himself failed to get access to the text himself, precisely because of his extreme interest in it.

Thereafter interest waned till Froude wrote his Two chiefs of Dunboy in 1889 which culminated in another great Cork lament, that for Morty Oge O’Sullivan, victim of another of the county’s singular political vendettas in 1754. This in turn prompted Mrs Morgan O’Connell to feature Irish and English versions of the lament for O’Leary, supposedly by a member of the O’Connell family, in her Last Colonel of the Irish Brigade in 1892. With the text published on another two occasions in the same decade, the Caoineadh Airt Uí Laoire never lost its place thereafter, and passed into the lore of modern Irish history.

Louis Cullen is Professor of Modern History at Trinity College, Dublin.

Further reading:

J.T. Collins, ‘Arthur O’Leary, the outlaw’, in Journal of the Cork Archaeological and Historical Society, liv (1949) pp1-7; lv (1950) pp21-24; lxi (1956)pp1-6.

M.J. O’Connell, Last colonel of the Irish brigade (Cork 1892, repr. 1977).

S. Ó Tuama, Caoineadh Airt Uí Laoghaire (Dublin 1961).

L.M. Cullen, The emergence of modern Ireland 1600-1900 (London 1981).