By Conor Robison

For an O’Neill, Charlemont fort was a symbol of defeat that bore the name of their conqueror. Purpose-built by Lord Mountjoy in the heart of Ulster on the banks of the Blackwater near the foundations of an earlier English fort previously vanquished by the arms of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, it was meant to ‘cut the traitor’s throat’, and in the year after Kinsale it did just that, at least in the strategic sense, for though Tyrone survived Charlemont’s construction his cause died in its shadow. Dungannon, his home and capital, burned as the permanency of Charlemont rendered it untenable, and within five short years the earl fled Ireland forevermore. Ironically, three decades later, another O’Neill would make of Charlemont Ulster’s last defiant bastion against the fell hand of the Cromwellians.

SIR PHELIM O’NEILL

That man was dubbed a military incompetent by contemporaries who found him ‘a well-bred gentleman’ but without the training ‘of a soldier’ so common to his family, a fact that left him wanting in ‘the main art … in war’. In spearheading Ulster’s uprising in October 1641, however, Sir Phelim O’Neill inaugurated his military career with a coup against the fort that defied military minds far greater than his own for the next nine years, a fort with which he became inextricably linked.

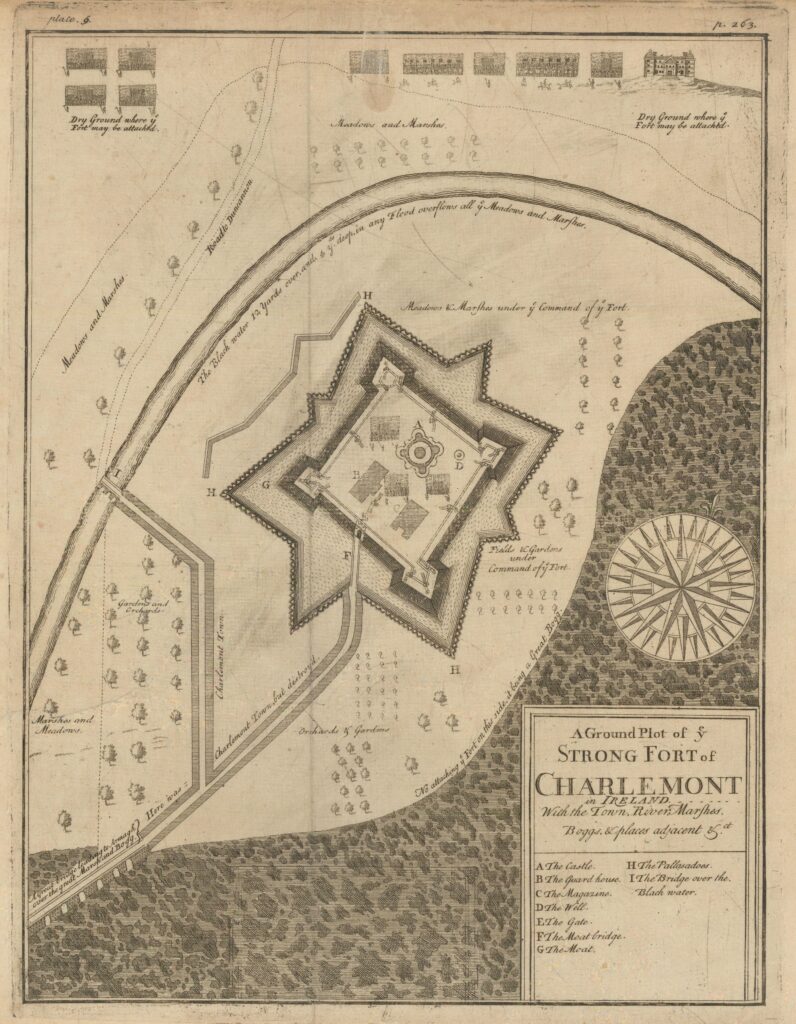

The Caulfields had held Charlemont since 1602, transforming it within its first decade from a mere forward garrison in an enemy’s country into a stronghold ‘with a palisade and bulwarks’ and a town ‘replenished with many inhabitants both English and Irish’. By 1624 the fort was crowned with a castle rising to three storeys in height over limestone walls, the bastioned perimeter enclosing less than four acres. Perched on a hilltop amidst bogs abutting the Blackwater, it commanded the bridge over the river and the wider country below Lough Neagh to the point that one veteran observed that ‘it might much trouble them’ that did not possess it. At the outset of the rising of 1641 Sir Phelim determined to possess it.

TAKING ON ALL COMERS, 1641–50

Being a good neighbour, O’Neill appears to have been a regular guest of the third Baron Caulfield and so was naturally welcomed into the castle on 23 October 1641, with a body of men. Once in, he seized his host and the latter’s home at the point of the sword. Strong as Charlemont proved to be, nothing could adequately defend against the breaking of the code of hospitality. Its surprise was the first of many such attacks that swept across Armagh and Tyrone, but it was the last time that decade that the fort would succumb so easily—though not for lack of trying.

The unexpected uprising of their Catholic neighbours caught many of Ulster’s Protestant settlers unawares, but they rallied and gamely held the provincial periphery until the following summer, when thousands of Scots reinforcements poured in to ignite a counter-offensive that saw O’Neill falling back upon Charlemont, his place of ‘greatest confidence’, a confidence that was not misplaced. Though lightly manned, Charlemont was always valiantly defended by garrisons whose numbers regularly fluctuated based on operational necessity. Strengthened in 1642 with a ‘strong and Handsome trench about the Towne’ and boasting a pair of brass field pieces, it became an even more difficult proposition to attack. With limited approaches through the bogs, and the blighted hellscape of Ulster unable to yield enough nourishment to sustain an army before it for long, the fort became a battle-scarred veteran that withstood onslaughts by Protestant armies successively in 1642 and 1643, and again in 1645.

As the military fortunes of the Catholic Confederacy ascended in the middle part of the decade and then evaporated through factionalism and military disaster at its end, so the fort’s allegiance shifted with the changing political winds. In England Parliament had triumphed over the king and took his head. Across the Irish Sea, meanwhile, a new Royalist alliance emerged under the Marquis of Ormond, whose aim, Cromwell warned, was ‘to root out the English interest in Ireland’ in the name of King Charles II. With this cause Sir Phelim now aligned himself, deserting his cousin Owen Roe and the hard-line Rinuccini, the pope’s representative, who refused any accommodation with the Protestant Royalists. Ormond promptly made Sir Phelim governor of Charlemont, a position that he held when the northern thrust of Cromwell’s conquest came against it in the spring of 1650.

THE SIEGE, JULY–AUGUST 1650

The expectation of a siege was made certain by the tragic slaughter of the Ulster Confederate army on a Donegal slope at June’s end. Owen Roe had died the previous November, but not before joining his forces to Ormond’s cause. An advanced element went south to help hold Munster against Cromwell, and at both Waterford and Clonmel had checked his pride. But these successes were mere mirages and not enough to check the New Model’s advance for good, nor could they rally their compatriots in the north into a united front. Instead, the Parliamentarians swiftly seized eastern Ulster, taking Carrickfergus in December 1649. Come the spring of 1650, Enniskillen was given over to the New Model Army as well, while the Ulster Irish leadership dithered in heated arguments over who should wear the mantle of Owen Roe. They came to the political expedient of electing the bishop of Clogher as commander of the army in March, a post that Sir Phelim’s earlier desertion excluded him from attaining.

Nevertheless, he marched with his countrymen to their collective annihilation at Scariffhollis on 21 June 1650, a slaughter prompted by Sir Charles Coote’s threat to Charlemont. ‘Till that place be reduced’, Coote had sworn, ‘Ulster will never be quiet.’ Indeed, to Parliament’s commander-in-chief in the north, the son of an Elizabethan soldier and Connaught planter, it was the key to Ulster’s subjugation and the last fort standing against his army. To its rescue the bishop of Clogher ventured forth in May but was ultimately outmanoeuvred and destroyed in a slaughter as consequential for the Ulster Irish as Kinsale had been for their forebears. Thereafter, Coote combined his forces with the regiments of Robert Venables, Cromwell’s personal choice ‘to join Sir Charles Coote to clear … Ulster’, and came at last before Charlemont two weeks after Scarriffhollis—enough time for Sir Phelim to get there before him and ready the fort for a final stand.

Having survived the Donegal massacre, O’Neill’s decision to head eastward instead of making for the Shannon, where the battered Royalist remnants were preparing their last-ditch effort, speaks to his courage and continued confidence in that rock of Ulster. He had once defiantly replied to calls for its surrender that he’d ‘sooner kill himself with his own hand’ rather ‘than betray his trust so meanly’. It had taken on all comers, and, as Coote and Venables thought themselves men enough for the task, Sir Phelim demanded that they prove it by force.

WALLS BREACHED

For six weeks they strove to overcome his challenge, as July spilled into August. O’Neill scrounged together a garrison ‘sevenscore’ in number, to which could be added the ferocity of the fort’s women, who stood more, it was said, ‘like fighting Amazons than Civilized Christians’. There would be no civility if the fort fell to an assault, and with no hope of relief Charlemont would have to make of itself a bloody prize before the Parliamentarians were given to negotiations or withdrew. With the weather—an ‘abundance of raine’, Venables complained—against them and the natural ‘difficulty of provisions’, the Parliamentarians could not stand before Charlemont indefinitely. A blunt approach to open a breach in the walls began, at the intimate distance of ‘forty or fifty yards of the wall’, until, having used ‘all the great shot of ordinance in the north of Ireland’, a breach was eventually made ‘assaultable’ on 6 August.

It was no mean feat attacking into so concentrated a kill zone as a breach, and for the New Model Army in Ireland such gaps cost more men their lives than open battle. It was no different here. The attack came head-on, cavalrymen dismounting to join the infantry in the storm, a storm met by shot and shell, ‘scalding urin water and burning ashes’. Though bearing themselves ‘with resolution and courage’, Coote’s men could not force the bloody gap after three hours’ ‘hot dispute’, and by day’s end the defenders would boast that they had killed upwards of 500 or more. The Parliamentarians openly admitted the loss of almost 300 men in this ugly reverse that now forced greater imagination upon their commanders. In the week that followed Venables records progress being made on a mine, one ‘almost perfected’, in fact, when Sir Phelim ‘sounded a parly’.

O’Neill’s defence had been tenacious, but the victory of 6 August had burned through his powder stores; though he had food enough to sustain the siege for another month, he would not have been able to fight on with so little powder and so few men. On the night of 16 August, he bravely appeared before Coote, his safety assured by two hostages given over to the garrison, and that night they hammered out an agreement that allowed O’Neill and what remained of Charlemont’s defenders to evacuate the fort the next day with their ‘armes and baggage’. Coote could be satisfied that with Charlemont’s fall the last of Ulster’s organised resistance was no more. Even in defeat, however, Sir Phelim’s accomplishment was unique. As one of the rising’s original leaders he was a tempting target, yet in an isolated fort without hope of relief he fought well enough that his enemy grudgingly let him depart with the honours of war, thereby ending his military career where it had begun, amidst the stalwart ramparts of Charlemont. He subsequently went on the run but was later captured, tried and executed in Dublin in 1653.

Conor Robison is a historian and creative writer from Chicago, currently pursuing an MA in military history at Maynooth University.

Further reading

P. Lenihan, Confederate Catholics at war 1641–49 (Cork, 2001).

M. Ó Siochrú, God’s executioner: Oliver Cromwell and the conquest of Ireland (London, 2008).

D. Stevenson, Scottish Covenanters and Irish Confederates: Scottish–Irish relations in the mid-seventeenth century (Belfast, 1981).