By Sandrine Tromeur

In the late 1630s and early 1640s, a handful of Irish Catholic merchants settled in La Rochelle, a French port city largely dominated by an élite of Protestant (Huguenot) mercantile families. Over time, the small Irish group gradually grew in number, and by the 1670s it had developed into a nascent community mainly composed of merchants, seafarers and their families. This community, like those of Nantes and Saint-Malo, received a fresh influx of merchants during the 1670s and 1680s. In La Rochelle commercial opportunities may have arisen for Irish Catholic merchants owing to the departure of Huguenots, who were increasingly affected by state repression that began in 1679 and culminated in the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. The influence of this Huguenot exodus on the growth of the Irish community should not be exaggerated, however. Rather, the expansion of Atlantic trade appears to have been the crucial factor in the influx of Irish migrants.

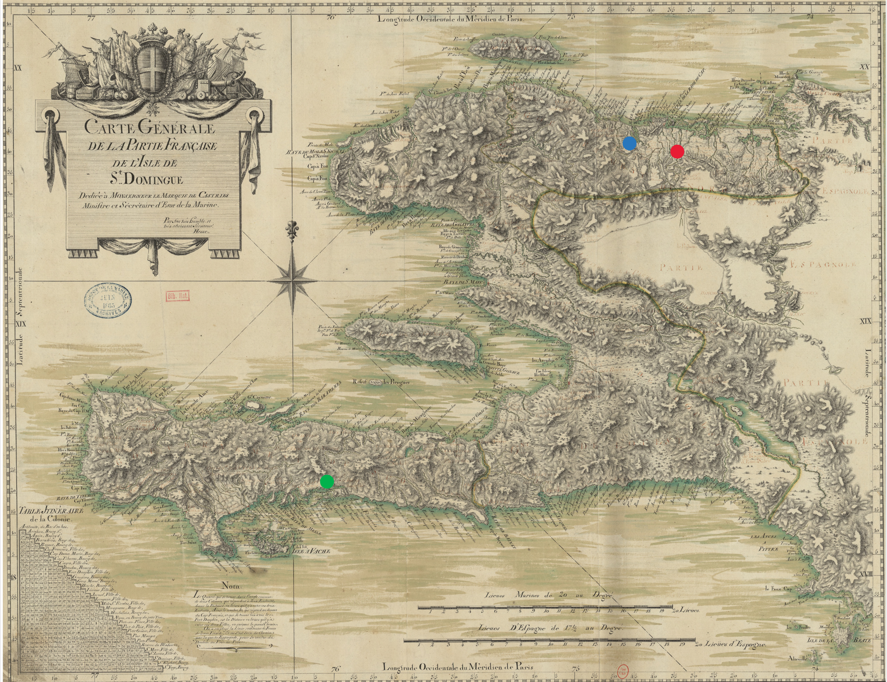

The younger Irish merchants who settled in La Rochelle during the 1670s increasingly participated in the Atlantic trade. For instance, Edmond Gould, originally from Kinsale and established in La Rochelle in 1677, organised six shipments to the ‘French islands of America’ between 1691 and 1698. In 1691 he arranged for his relative Francis Gould to travel aboard his ship, L’Aigle Noir, to Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti), where Francis worked as his clerk for four years. From 1715, Irish merchants in La Rochelle became more directly involved in the development of the French colonial empire, especially in Saint-Domingue. The second generation of three Irish families, the Butlers, MacCarthys and Bodkins, purchased plantations on the island and spent part of their lives in the colony.

BUTLERS

The Butler family was the longest settled in La Rochelle. The presence of its first member, Richard Butler from New Ross, is attested from 1647. He was joined in La Rochelle before 1669 by John Butler of Galway (no relation), who married Richard’s daughter Marguerite in 1675. By 1682 John Butler was trading with ‘the French islands of America’ and formed a five-year business partnership with Andrew Lynch. Lynch was charged with selling a cargo of merchandise and using the profits to establish himself in the French colonies. According to their agreement, the profits generated were to be equally divided between them. After John’s death in 1704, his son, Jean Butler, initially under the guidance of his mother, took over the family’s business. He traded extensively with Saint-Domingue and organised twelve shipments between 1704 and 1715. In September 1715 Jean’s younger brother, Richard Jean Butler, at the age of 25 captained his ship, Le Saint Jean, on a voyage to Saint-Domingue. He did not return to La Rochelle and instead chose to settle in the colony, where he married in 1716. His relocation was part of the first wave of colonial settlement of the island between 1700 and 1720, particularly in the northern plains, which were particularly fertile and suitable for sugar plantations. Shortly after his wedding, Richard Jean Butler purchased a sugar plantation in Bois de Lance, located in the northern plains. This acquisition was a family investment: Jean Butler financed the purchase for over 140,000 livres tournois (roughly €1.5m in today’s money) in exchange for receiving the sugar production in La Rochelle. Following the death of his wife, Richard Jean Butler left the colony in 1722 with his two young sons, but he died at sea during the return journey. Before 1729 another brother, Antoine Robert Butler, was sent to Saint-Domingue to manage the plantation, where he stayed until 1743. When they reached adulthood, the sons of Richard Jean co-owned the plantation and lived between La Rochelle and Saint-Domingue. The Butler family expanded their holdings on the island through additional acquisitions and marital alliances until the French Revolution in 1789.

MACCARTHYS

In the second phase of the colonisation during the 1740s, Denis MacCarthy and Patrice Bodkin, both born in La Rochelle, relocated to Saint-Domingue. Denis, born in 1716, was the son of Timothy MacCarthy of Timoleague, Co. Cork, and Helene Shea from Kilkenny. The circumstances of their arrival in La Rochelle differed from those of the Butler family. Timothy MacCarthy was attainted for high treason in 1690 and probably migrated to France in the aftermath of the Treaty of Limerick. His case is one of the rare documented instances of involvement with the Jacobite cause among the Irish population of La Rochelle. Timothy first settled in Brest, where he met and married Helene Shea in 1701. The couple moved to La Rochelle in 1715. Their youngest son, Denis, qualified as a ship’s captain in 1741. He worked for La Rochelle’s merchants for several years before relocating to Saint-Domingue in his early thirties, sometime between 1746 and 1748. There in December 1748 he married the daughter of a merchant from Le-Cap-Français. The couple owned a house in the city and a small sugar plantation in the northern plain at L’Acul. Denis maintained a sociability with other planters of Irish origin on the island. His plantation was located near both a Walsh plantation and a Butler plantation, and a Stapleton was present at the baptism of his daughter Marie-Barthelemy in 1753.

BODKINS

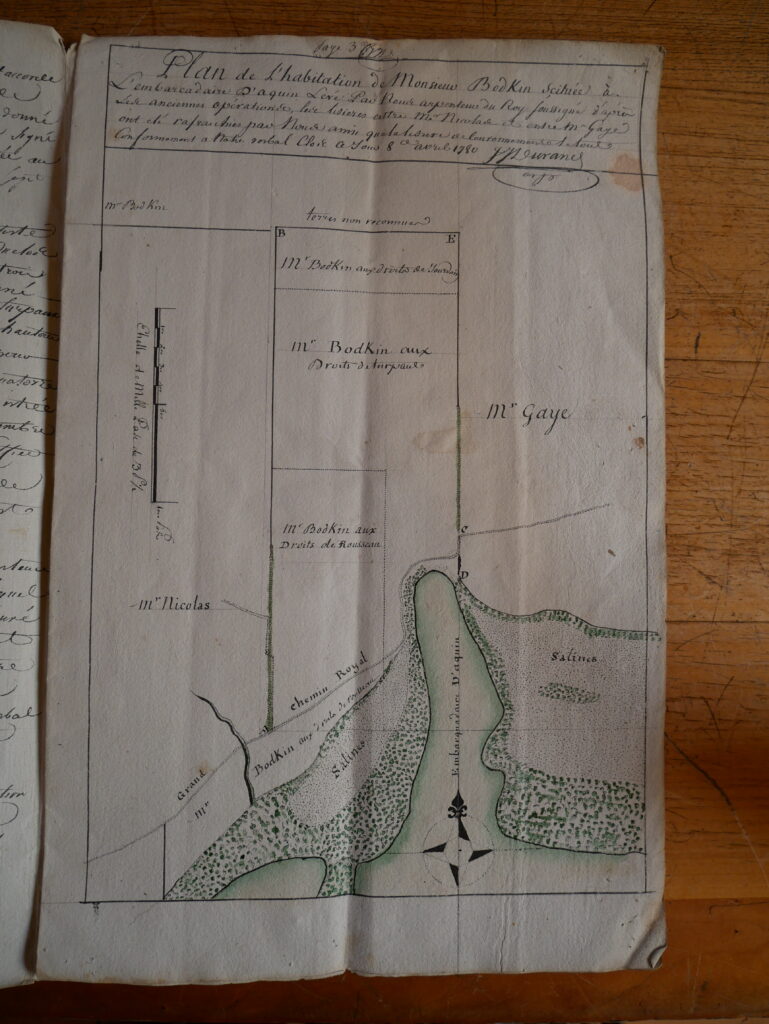

Born in La Rochelle in 1718, Patrice Bodkin was the son of Robert Bodkin and Elizabeth Butler. His father, a cousin of John Butler of Galway, arrived in the city in 1711. Like Denis MacCarthy, Patrice Bodkin relocated to Saint-Domingue in the late 1740s. He settled in the southern part of the island, in the locality of Aquin. This area had been planted in the 1720s and 1730s and was initially exploited for indigo, as the dye grew naturally there. Bodkin owned two large plantations: L’Embarcadère covered 230 acres and was situated near the coastline, and L’Hermitage, a 600-acre estate, was higher up in the hills. For a brief period Bodkin also owned a sugar plantation, which he sold in 1760.

Denis MacCarthy and Patrice Bodkin came back to La Rochelle in 1765, following the end of the Seven Years’ War (1756–63). At the age of 47, Patrice Bodkin married Geneviève Blavout, daughter of a rochelais merchant. Denis MacCarthy’s return may have been prompted by the death of his older brother in January 1765. Denis made a flamboyant return to his native city and immediately purchased in February 1765 a large townhouse for 22,000 livres tournois (roughly €0.25m in today’s money). Within the subsequent two and a half years he spent a further 165,000 livres tournois (roughly €1.8m in today’s money) on various real estate acquisitions, including salting marshes, the estates of La Cotinière and La Martière on the island of Oléron, and a manor house and its vineyard in the countryside near La Rochelle.

POLICE DES NOIRS

Denis was not the only one who travelled from Saint-Domingue to La Rochelle. He was served in his townhouse by enslaved people brought from his plantation. In 1777 a census was conducted in French port cities to record the presence and status of people of colour as part of the enforcement of the Police des Noirs. Introduced by Louis XVI, this law sought to restrict slave-owners from bringing enslaved people to metropolitan France, where slavery was theoretically prohibited, and to encourage them to return enslaved individuals to their plantations in the colonies. As a result, four enslaved individuals were recorded in Denis MacCarthy’s house—the highest number in a single household in La Rochelle. He justified their presence in La Rochelle for training purposes, but they never returned to Saint Domingue. In 1783, three weeks before his death, Denis drafted his will, in which he expressed his intention to free the four slaves and provide them with pensions. This freedom was conditional, however: they were required to continue serving his wife and, after her death, his children.

JOINED THE NOBILITY

The profits from the plantations enabled the Irish families to consolidate their position in France and to pursue their social ambitions in French society. The three men sought to establish their pedigree through the office of the Ulster King of Arms. Jean Baptiste Butler, son of Richard Jean Butler, obtained his certified genealogy in 1750. He subsequently styled himself ‘Comte de Butler’, and his brother Pierre Antoine took the title ‘Chevalier de Butler’. The pedigree was accepted by the French judge of Arms in 1760. Denis MacCarthy obtained his pedigree in 1767, and two years later a letter patent from Louis XV confirmed his noble status. His son, Charles Denis MacCarthy, adopted the title ‘Vicomte MacCarthy’ around 1786. Similarly, Patrice Bodkin received his certified pedigree in 1771. The formal recognition of their noble status, coupled with the substantial wealth received from the plantations, enabled the descendants of Irish migrants to marry into French high society. For instance, two of MacCarthy’s daughters married into prominent landed families, and in April 1789 the youngest married the Comte du Chaffault, future marquis. The three brides each received a dowry of 120,000 livres tournois (roughly €1.3m in today’s money), paid in cash shortly after the weddings.

Managing overseas plantations from metropolitan France was not without challenges. In 1780 Denis MacCarthy appointed a new estate manager to oversee his plantation, but he seemed to have doubts about the manager’s capabilities, as he appointed two acquaintances to monitor his work. His concerns confirmed, MacCarthy dismissed and replaced his manager in 1782. Robert Étienne Patrice Bodkin, who inherited his father’s plantation, faced similar difficulties. He discovered irregularities in the account books and demoted the plantation manager in 1787. Not all relationships between plantation owners and managers were problematic, however. Jean Pantaléon Butler appeared satisfied with Villevaleix, who proved to be highly competent. In 1785 Villevaleix documented new work undertaken on the river Fossé de Limonade bordering the plantation at Bois de Lance and expressed concern that the river was not deep enough, posing a risk of flooding to the plantation. Recent research by Finola O’Kane has demonstrated how the Walsh and Butler families played a pivotal role in the development of the Limonade area, particularly in controlling water resources for irrigation, operating water-powered mills and regulating flooding. Plantation owners were attentive to improving all aspects of their plantations to increase profitability. Butler provided Villevaleix with pre-printed sheets to simplify and standardise his monthly reports. In 1785 Bodkin, in consultation with his manager, decided to progressively convert one of his plantations, L’Hermitage, from indigo to coffee cultivation, as indigo yields were declining.

FRENCH REVOLUTION

Despite all their efforts to manage their overseas plantations effectively, the onset of the French Revolution in 1789 disrupted the fortune of the Irish plantation owners, who responded in diverse ways to the unfolding events. Jean Pantaléon Butler promptly reacted against revolutionary ideals. He was a founding member of the Club Massiac in Paris, an influential lobbying group representing the interests of white plantation owners. His brother-in-law, Yves Cormier, served as the club’s vice-president in 1789 and as its president in 1791. Its members had differing views on the plantations’ future; some opposed the implementation of free trade while others sought to restrict state encroachment on their affairs, but there was unanimous agreement on the necessity of maintaining slavery. Charles Denis MacCarthy joined the regional branch of the club in La Rochelle, but he was less involved with the organisation than Butler. In contrast, Bodkin reacted more positively to the Revolution and was elected as a substitute representative for Saint-Domingue in the Assemblée Constituante. He appeared to hold more liberal views concerning the rights of free people of colour and mixed-race children, although he remained in favour of slavery and continued to own his plantation. Just two months before the storming of the Bastille, an inventory of his plantation was carried out, which not only listed its material possessions but also documented the enslaved people working on the estate—89 individuals were recorded, including fourteen who bore ‘BODKIN’ as a branded mark.

Although they reacted differently to the onset of the French Revolution, these three Irish families in La Rochelle benefited equally from the expansion of the French colonial empire during the eighteenth century. The second generation of the Butler, Bodkin and MacCarthy families capitalised on the development of the French colonial empire and its slavery system to secure their position. They amassed significant wealth, which allowed them to enhance their social status and be absorbed into the higher ranks of French society.

Sandrine Tromeur is a Ph.D student at Maynooth University, funded by Research Ireland, a government of Ireland postgraduate scholarship.

Further reading

K. Hodgson, ‘Franco-Irish Saint-Domingue: family networks, trans-colonial diasporas’, Caribbean Quarterly 64 (3–4) (2018), 434–51.

É. Ó Ciosáin, ‘Hidden by 1688 and after: Irish Catholic migration to France, 1590–1685’, in D. Worthington (ed.), British and Irish emigrants and exiles in Europe, 1603–1688 (Leiden, 2010), 125–38.

F. O’Kane & C. O’Neill (eds), Ireland, slavery and the Caribbean: interdisciplinary perspectives (Manchester, 2023).

G. Ohlmeyer, Making Empire: Ireland, imperialism, and the early modern world (Oxford, 2023).